'The Zone of Interest': The Immersive Disquiet of Holocaust Atrocity

I was tempted to make this review my shortest one yet at only five words long: "You must see this film." Words can only go so far when describing Jonathan Glazer's hauntingly grim immersive experience, The Zone of Interest. Winner of the Grand Prix at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, this Holocaust-set drama is a chilling portrayal of history's most atrocious cruelties. If you're like me, it will leave you speechless.

Based on the biographical novel by Martin Amis, The Zone of Interest views the devastating events of the Holocaust from the perspective of a German militia family. The phrase "Zone of Interest" was commonly used by the Nazi SS to describe the small area immediately surrounding the Auschwitz concentration camp. And it's here where this film takes place.

The commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), attempt to build a dream life for their family despite being surrounded by the consistent sounds of suffering and death. Their picturesque home and luscious garden lay in stark contrast to the concentration camp that borders their property. As much as Hedwig and her young children seem to easily drown out the sounds of gunshots, crying, and screaming, we as viewers know that there is no escaping the horrors that are taking place behind the walls. Inside the family's home is a haven; but step one foot outside, and it's hell.

When Rudolf is informed that his superiors want him to move to a different city, Hedwig is beside herself. She refuses to leave the beautiful home she made for herself and, for a while, their marriage is only barely surviving. Rudolf views his responsibilities as a death camp commandment with the utmost respect and obeys his orders, taking this new position as an opportunity to better provide for his family. It's a morality mind warp, as on one hand, Rudolf cares so little about human life that he is actively encouraging mass genocide. On the other, he sacrifices everything to give his family the best life he possibly can. As a viewer, confronting guilt, conflict, and humanity comes in unpredictable, emotional waves.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-vfg3KkV54&ab_channel=A24

Witnessing the atrocities of the Holocaust from a perspective we don't often see–that of the Germans–is one of the reasons why The Zone of Interest is such an uncomfortable watch. There reaches a point where the screams from behind the concentration camp walls become almost ambient, like a horrific yet subtle soundtrack that plays in perpetuity. Adding to the discomfort is the intentional lack of any musical score. Composer Mica Levy (Under the Skin, Monos) contributed ambient-heavy, noise-distorted sound to aid in the opening and end credit roll, but aside from those two moments, there is no additional music. Instead, sound designer Johnnie Burn is heavily relied upon to craft a sensational auditory world that runs concurrently with what is playing onscreen.

Capturing the nuances and complexities in stunning detail is cinematographer Łukasz Żal (Ida, Cold War, I'm Thinking of Ending Things). True to form, Żal's compositions are masterfully composed, even with Glazer's unconventional production technique. Fixed and partially hidden cameras were placed around the entire family house, and the actors were required to perform long, unbroken takes, never knowing which moments would be used in the final edit. Due to the nature of the shoot, Friedel and Hüller were tasked with improvising some scenes while others were carefully scripted.

For most of the production, Glazer and Żal watched the scene play out through monitors while stationed in a separate concrete bunker with a team of focus pullers working via a system of remote cables. Says Glazer: “The phrase I kept using was ‘Big Brother in the Nazi house.’ We couldn’t do that, of course, but it was more like the feeling of ‘Let’s watch people in their day-to-day lives.’ I wanted to capture the contrast between somebody pouring a cup of coffee in their kitchen and somebody being murdered on the other side of the wall, the co-existence of those two extremes.”

The performances from Christian Friedel and Sandra Hüller as stiff and detached protagonists are among the year's best. They keep the audience at arm's length, and their vacant eyes say more than any words could. Psychologically mystifying, the duality of playing a character with human emotions, yet seemingly devoid of apathy, is a fine line to walk. Yet Friedel and Hüller walk it with a stark, horrifying precision.

The Zone of Interest is, at its core, a rather simple story about one Nazi family's existence and contributions to one of the worst events in human history. It's a difficult film to witness and an even more difficult one to forget.

'The Taste of Things' Is a Transfixing Culinary Triumph

Perhaps one of the most viscerally indulgent films of the year, filmmaker Tran Anh Hung's The Taste of Things offers a sizzling, gastronomic treat that aims to satiate all of the senses. At the heart of the film is a tender love story between two middle-aged cooks in their "autumn" years whose commitment to each other consistently reverberates throughout their rich, albeit, repetitive life.

The year is 1889 and Eugénie Chatagne (Juliette Binoche) can be found doing what she does best: cooking. Commanding the kitchen as if on auto-pilot, Eugénie waltzes around the stoves and counters with stunning confidence and finesse. No recipe books to be found, she adds thinly sliced vegetables to the pot au feu, dashes of salt to the brine of fish, and whole milk to the pastries that will no doubt come out perfectly golden brown. Eugénie is a food artist and is highly respected by chef Dodin Bouffant (Benoît Magimel), whose meals are often prepared for him and his friends by Eugénie.

Admiring more than just her skills, Dodin is infatuated with Eugénie and expresses his love often. The two cooks have worked together for over 20 years and their love for each other has sustained time, growing stronger with each passing year. It is never explicitly addressed why Eugénie has kept Dodin at a distance, romantically speaking, despite clearly having so much love for him, too. However, their love circumvents the need for traditional labels. They express their devotion through the food they prepare for each other; acts of service are their love language and they are fluent in their declaration.

The Taste of Things is nothing if not a flavorful feast for the eyes and ears. The opening of the film takes audiences on an artful journey through the intangible senses as we watch Eugénie and her young apprentice prepare a multi-course meal fit for a king. With such synchronicity–as if choreographing a ballet–we watch her quietly create some of the most gorgeous plates of French cuisine to ever exist on screen. It's almost comical how appetizing the food looks and how we can practically taste every individual course in such fine detail. Three-star chef Pierre Gagnaire served as a consultant on the film, helping director Tran Anh Hung achieve perfection on a plate.

Juliette Binoche delivers a reliably strong performance as the self-assured Eugénie, her grace and embodiment of the character are truly felt. Acting opposite Binoche is Benoît Magimel, her real-life former partner and father to their daughter, Hana Magimel. Binoche shared this connection in an exclusive Q&A during an early screening to a stunned audience, who mostly had no idea there was a prior history between the two leads. This personal backstory aids the film in insurmountable ways. Another unconventional takeaway is that for as much joie de vivre that surrounds The Taste of Things, there is a noticeable lack of score. A singular piano piece from Jules Massenet’s opera “Thaïs” is the only musical element in the film, however, the film never lacks for sound. The elements of cooking–sizzling butter, burning wood, running water, chopping vegetables–all aid in creating the film's aroma-based soundtrack.

The richness that seeps throughout the scenes in The Taste of Things is a vision to behold. Let yourself get washed away in the sights and smells of Tran Anh Hung's transfixing culinary triumph.

In 'Cypher,' Rapper Tierra Whack Confronts A Stalker

Tierra Whack does things differently. The 27-year-old rapper from Philadelphia is using a medium other than music to let fans get a sneak peek into her world in her off-the-wall documentary Cypher, which won Best U.S. Narrative Feature at the 2023 Tribeca Film Festival. From a 15-year-old street rapper who went by the name “Dizzle Dizz” to signing to Interscope Records and receiving widespread critical acclaim in only a few years, Tierra is a force of nature. Her talent is undeniable, her style is unapologetically bold, and her confidence serves as inspiration. That much we know about Tierra Whack. But Cypher cheekily shows that there is much more to be discovered.

Cypher is billed as a pseudo-documentary, akin to the 2020 Sundance-selected The Nowhere Inn, starring St. Vincent and Carrie Brownstein. Whereas I wasn’t a big fan of the latter, I’m happy to report that Cypher’s execution nails the undefinable tone, perfecting the balance of authentic musical moments and self-aware mystery plots. Written and directed by Chris Moukarbel (Gaga: Five Foot Two, Banksy Does New York), Cypher grants access to Tierra’s life behind the scenes.

The film starts out simple enough, we see her in the studio, hanging out with friends, and performing in front of thousands of fans. Things take a turn after one of her shows, where she engages in a conversation with a woman she thought was a fan. Turns out, the fan, Tina Johnson-Banner is a conspiracy theorist who has been stalking Tierra both in person and online. Tina is a devout follower of a secret cult that claims Tierra Whack is the chosen one, their messiah, and won’t stop until the occult ritual is complete.

It serves to point out that the title Cypher is very intentional. One meaning of the word, perhaps more obvious, is a message written in a secret code. The other usage is to describe a gathering of rappers in a circle who make music together. This double meaning is indicative of the film’s slyness and hidden-in-plain-sight message.

Enjoyably self-aware, uncomfortably humorous, and poignantly dark, Cypher is an entertaining watch with a message. Through a consumer-friendly lens, it points out the many dark sides of being a public figure and how “fame” puts personal safety at risk. Especially in the age of social media and parasocial relationships that fans can develop with their ideals, Cypher proves that you never know who’s truly watching you.

This review originally ran on June 23, 2023 during the Tribeca Film Festival

In 'Smoke Sauna Sisterhood' Women Bare Their Bodies And Souls

Imagine a sauna in the middle of a snowy forest. The smell of steaming rocks, burnt embers, and warm cedar infiltrates your senses. If you're like me, a feeling of ease immediately floods your body. A deep inhale, followed by an even deeper exhale dispels all feelings of negativity and stress. Here, secluded from the distractions of the outside world, the mind is free to roam.

In Smoke Sauna Sisterhood, which premiered in the World Cinema Documentary category at this year's Sundance Film Festival, director Anna Hints dedicates her film to the sacred Estonian tradition of "savvusanna kombõ," or, smoke saunas heated by a stove. For an hour and a half, we feel as if we are among a local group of women who frequent the sauna to cleanse their bodies and minds and connect with fellow feminine spirits.

Smoke Sauna Sisterhood follows a very loose narrative structure. Forgoing a linear storyline, the film plays mostly like a fly-on-the-wall observational documentary. Nameless women of all ages and sizes gather at the sauna deep in the southern Estonia forest. There, they bare not only their bodies but their souls. Each with a story to tell, the women take turns leading vulnerable conversations around such topics as sex, relationships, cancer, shame, body image, and death. Much like a church confessional, the sauna acts as a safe space for complete honesty, no matter how complex the topic at hand is.

The film draws a poignant parallel between women and mother nature: both act as a resource for life. This sentiment is explored abstractly through their stories and in respectfully photographed images of their naked bodies. The environment of the film is also completely absorbing and stunning. Cinematographer Ants Tammik highlights the rich, organic colors of the Estonian outback from the depths of the damp sauna to the purity of the vast, snow-covered ground. Seeing these women set against this backdrop is nothing short of magical.

Smoke Sauna Sisterhood is a striking celebration of natural beauty in all forms. For as vulnerable as these women seemingly are – naked and confessing to shortcomings or defeats – their strength is beyond measure. The film's intimacy, combined with universally poignant themes, makes Smoke Sauna Sisterhood a rare, much-needed cinematic escape.

This review originally ran on January 29, 2023 during the Sundance Film Festival

https://youtu.be/u57aVf1-SBk?si=AscSKNBZ90iSec0J

'Maestro' Hits All The Right Notes With Stunning Finesse

A star was born in Bradley Cooper's directorial debut, and that star has matured into a force of nature in his sophomore feature, the Leonard Bernstein biopic, Maestro. The depth of beauty runs deep throughout the film's 129-minute runtime, as Cooper offers audiences a richly observed panoramic portrait of a misunderstood artist whose music contributed to some of the most unforgettable scores of all time. Starring as the multi-hyphenated conductor/composer himself, Bradley Cooper's ability to capture magic both onscreen and off is a sight–and sound–to behold. Move over Lydia Tár, there's a new maestro in town.

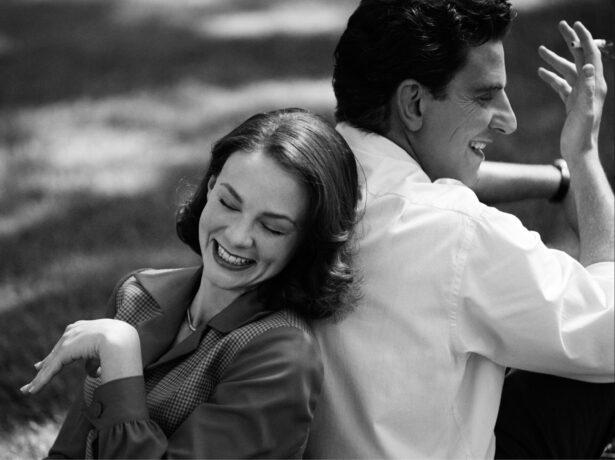

The biographical drama serves as a character study of Leonard Bernstein (Cooper) at five different pivotal stages in his life. Spanning 25 years young to 71 years old, the film's primary focus isn't solely centered around musical achievements or performances. Rather, audiences embark on a decades-long love story between the flighty Bernstein and the grounded and mature love of his life, actress Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan). The film weaves through their lighthearted honeymoon phase with a stoic black-and-white color grade. Signaling a sense of reminiscence for the past, nearly half of the film is portrayed in black and white. During this time period, both Bernstein and Montealegre's careers accelerate, albeit at different paces and scales, and signs of tomfoolery on Leonard's behalf become apparent. We learn that Leonard, prior to marrying Felicia, had been in a relationship with a man (Matt Bomer) and his attraction to men is still very much being acted upon. This creates a growing conflict within their relationship, and an internal explosion within Felicia is embodied in the film as it visually transforms into color.

The couple's intricate and complicated relationship dynamic fills the second half of the film, which is now portrayed in stunning color. Family, friends, instruments, and cigarettes come in and out of every scene, it is fully captivating both visually and musically. The film's sudden color switch causes our eyes and ears to perk up with the expectation that something big will be coming, and oh boy, does it deliver. In perhaps one of the finest musical scenes I've ever witnessed in a movie, Bradley Cooper takes the stage near the end of the film's third act and gives the performance of a lifetime. His embodiment of Leonard Bernstein conducting a full orchestra and choir in a six-minute stunning one-take had chills running down both of my legs. Taking place in an equally beautiful old church, the grand concerto comes to a dramatic end, and the audience I was sitting with erupted into rapturous applause, myself included. I think we collectively forgot that this is a movie and not a full-bodied, 3-D experience accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra. It was a moment that resonated with me more than any other film moment this year.

The craftwork that makes up Maestro is impeccable, from the costumes to the makeup and prosthetics used to portray Bernstein's later years. The richness and nuanced characteristics are captured by the master of photography, Matthew Libatique, in stunning detail. Playing to the strengths of both the black and white and color, Libatique brings the man and the music to life. Further reviving the virtuoso's story is the score, which were all instrumental works pulled from the Bernstein archives.

On the performance front, Bradley Cooper fully transforms into Leonard Bernstein and at times, it's easy to forget that this isn't a documentary. His speech pattern and his physical performance are magnetic, it's hard to look at anyone else when he's on screen. That's not to say Carey Mulligan isn't also a dynamic force, but her strength comes from a more subtle place. The opportunity to explore Leonard and Felicia's yin/yang personalities–independent of and with each other–is an actor's playground. There is so much material to devour yet Cooper and Mulligan never let the combative and unpredictable nature of the Bernsteins' relationship feel forced or unnecessarily fraught.

Maestro is the result of a finely tuned synchronicity from all sides. Performance, direction, aesthetics, and craft all contribute to this monumental work of art. Some may be baffled to hear that the musical component of Bernstein's legacy plays second fiddle to his complicated love story, but rest assured, there is no shortage of awe-inducing moments that will have you whispering "wow" from under your breath. Maestro hits all the right notes and then some.

'Saltburn' Is a Glossy Romp Through Hipster Affluence

If Saltburn was a person, he would be that hipster kid with main character energy. The unchallenged confidence and colorful charisma make for a staggering first impression but behind the initial charm exists a desperation to be seen as cool. Following her directorial debut Promising Young Woman, filmmaker Emerald Fennell crafts a slightly edgy film about loud luxury that skews favorably toward Gen Z. Saltburn offers a fun enough viewing experience but I'm not sure it's sticky enough to stay in the public consciousness for long.

Much like a modern-day adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley for the streaming generation, Saltburn tells the rags-to-riches story of college student Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan). Entering his first year at Oxford University, Oliver struggles to fit in with his high-society peers. A chance encounter with the (objectively) gorgeous aristocrat Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi) brings Oliver into a world that, up until then, had been far from within his reach. As summer break approaches, Felix invites Oliver to spend the next few months with him at Saltburn, the grand English manor that has been in the Catton family for generations. Given Oliver's dysfunctional family dynamic and subsequent vow that he would never step foot in his childhood home again, he graciously accepts Felix's invitation.

Upon arriving at Saltburn, there is a period of adjustment for Oliver who is not used to wearing full black tie attire to dinner and having waitstaff at every beck and call, but it only takes a couple of days to adapt to the Catton's laissez-faire lifestyle. It's not long before he too is peacocking as an heir to the Saltburn estate, much to the delight of Felix's delusional parents Sir James (Richard E. Grant) and Elspeth (Rosamund Pike). Oliver is becoming obsessed with his newly adopted association with wealth, power, and–more disturbingly–Felix.

There's a saying that goes, "Eat the rich", but in this case, it's more like "Drink the rich's bath water." As Oliver continues to lose himself in Saltburn, the darker and more voyeuristic his actions become. It's apparent that Oliver is in love, but with who–or what–is the burning question. From here, the film explodes into a dizzying array of power games, privilege, seduction, and madness.

Despite the abundance of riches that purposefully bloat the film, there is a superficiality that lingers throughout Saltburn as if the whole thing is playing too safe. It's provocative enough at times to garner gasps from the audience (and is definitely not a kid's movie by any means) but it seems to stay too comfortable on the surface rather than digging deeper and exploring more complex depths of the narrative. Working with what they have on the page, the performances are deliciously satisfying. Barry Keoghan is by far the scene stealer and brings an undeniable electricity to the role of Oliver. Watching his career trajectory from co-starring in The Killing of a Sacred Deer and American Animals to headlining major studio films like The Banshees of Inisherin and Saltburn has been so rewarding to experience. Visually, every frame looks like a glossy pop-magazine come to life. Shot in stunning detail by Damian Chazelle's go-to cinematographer Linus Sandgren, Saltburn's richly crafted aesthetic plays in perfect unison with the onscreen shenanigans.

Emerald Fennell's sophomore feature is a time capsule of mid-2000s glamour and full of sweaty, horny college students. The nostalgia is nice but not substantial enough to carry the film on its own. There is a line early on in the film when Oliver engages in a debate with his professor and fellow classmate about style vs substance, arguing "It's not what you say but how you say it." Unfortunately, Fennell follows Oliver's methodology, Saltburn is all style and limited substance.

'Aligned' Is a Gorgeous Meditation on Self-Acceptance

Captivating scenery and hypnotic movements run abundant in writer/director Apollo Bakopoulos' heartfelt film, Aligned. The gorgeous opening dance montage and accompanying piano score sets up audiences for an intimate evolution of self-reflection as we watch Aeneas, an aspiring professional dancer, embark on a life-changing journey of self-discovery. Making its World Premiere at the 2023 Brooklyn Film Festival, Aligned is an inspiring watch that comes with a positive message, leaving the viewer with a sense of good vibrations and a tangible spark of self-confidence to carry with them throughout the day.

Aeneas (Panos Malakos) seems to have it all, a supportive girlfriend, his health, and the opportunity of a lifetime: a three-month residency to train at a dance academy in Greece, which will bring him closer to his ultimate goal of becoming a professional dancer. He arrives in Athens from New York City full of excitement and open to the possibility of what lies ahead. Once at the studio, he is immediately introduced to Alex (Dimitris Fritzelas), a fellow dancer who quickly becomes a friend. Intimacy is the universal dancers' language and the closer the two men become on stage, the more that translates off stage as well.

Through their shared cultural heritage, Aeneas and Alex find a deep and unexpected connection they both acknowledge is worth exploring further. Aeneas expresses his lack of self-confidence and vulnerability to a receptive Alex, who offers non-judgemental comfort and support. His advice, to lead with the heart rather than the mind, is a common phrase repeated throughout Aeneas' self-discovery journey. At a crossroads with his newfound queer interest in Athens and a deteriorating relationship with his girlfriend at home, Aeneas is finally able to confront his deep-rooted insecurities and feel the transformative power of self-love.

Running 78 minutes long, Aligned jumps into the crux of the story immediately and doesn't linger on supplemental details or scenes that drag the material down. The filmmaker could have been tempted to linger on the dance sequences and additional distractions, however, the decision to stick to the bare bones of what is necessary is a mature and respectable approach. The fluid camerawork that captures the beautiful dance montages between the two men embodies the feeling of freedom and non-sexual physical intimacy. One scene, in particular, stands out as truly stunning, when the men improvise a dance in their apartment. This is the first time they advance from the boundaries of platonic friendship into a more emotionally invested relationship. Without words, they convey everything we need to know.

Filmmaker Apollo Bakopoulos creates a gateway to openly discussing one's insecurities and struggles with low self-esteem in Aligned, showing that living authentically is the only true path to happiness. Aeneas' struggles are meant to hold up a mirror to our own self-sabotaging habits, and Alex's words of affirmation are intended to resonate with us as well. Fear and familiarity have been the invisible chains holding Aeneas back from embodying his true self. It's scary forging into the unknown, but it's even scarier living in complacency and regret. Through the captivating dance and photography of Aligned, we are offered a gentle reminder that self-acceptance is a journey and takes time. There is no linear path, and forward momentum leads to freedom.

'All of Us Strangers': Enter the Liminal Space Where Love and Loss Co-Exist

If you look closely, you'll see writer/director Andrew Haigh hidden in plain sight throughout the melancholic romantic drama, All Of Us Strangers. Loosely adapted from the Japanese ghost story Strangers, written by Taichi Yamada in 1987, Haigh infuses chapters from his own life story into this mesmerizing tale of love, loss, and second chances. His personal connection to the material makes the film feel that much more fragile; Haigh's finely tuned singular experience doesn't omit his audience but rather, it creates a universal resonance where audiences can see themselves reflected in the film too.

Adam (Andrew Scott) lives a quiet (albeit, seemingly lonely) life as a queer screenwriter living in an apartment tower in contemporary London. The film opens with a gorgeous skyline shot of a blood-orange sun, marking the end of another unproductive day for Adam. His recent attempt to put pen to paper on his latest screenplay is coming up fruitless. He moves apathetically, going through the motions of the evening until an interruption by his mysterious neighbor, Harry (Paul Mescal). Harry is a charmer and unabashedly flirtatious. In a bold move for this near-stranger, Harry invites himself inside Adam's apartment and subsequently proceeds to pierce a hole in Adam's self-protective armor. This is jarring for Adam since he has lived his life in subdued modesty but sensing the start of a personal evolution, he embraces Harry and the unknown.

As Harry begins chipping away at Adam's tough exterior, offering him the space to feel safe exploring a relationship with a man, another revelation is on the horizon for Adam. Looking for inspiration for his script, Adam turns to old photos from his childhood. This walk down memory lane triggers something internal and Adam is inexplicably drawn to make a pilgrimage to his childhood home where he lived with his mum and dad (Claire Foy and Jamie Bell) before their sudden deaths. Adam was only 12 years old when his parents died in a car crash over the Christmas holiday, and since then, he has learned to cope by pushing down any emotions surrounding their existence. As he reaches the house, a flood of visceral memories come rushing back as Adam sees his parents standing before him, just as they looked 30 years ago. Is this a dream? It must be, but it feels very real to Adam. Regardless, this surreal experience gives everyone–dad, mum, and child–the opportunity to finally have proper closure and a final goodbye.

The fragility that stems from an adult man reckoning with childhood trauma is a devastatingly cathartic experience to witness. Andrew Scott was born to embody the role of Adam, his nuanced mannerisms and sensational performance are heartbreaking as we see a scared boy hiding inside a grown man. Scott plays Adam's vulnerability journey with such a dynamic range–he starts off fairly constricted and uncomfortable but over the course of the 105-minute runtime, he is exploring a cacophony of emotions. Acting opposite Scott is Paul Mescal's Harry, a good-natured free spirit who wears his heart on his sleeve. Their dynamic is raw, at times fraught with miscommunications, but at the foundation is an acceptance that we would be lucky to be immersed in.

Haigh captures the tone of All of Us Strangers through the use of 35mm film to evoke the "texture" of memory. This analog vessel is an embodiment of the time period as well as the sentiment that memories, much like the physical element of film, can fade or become distorted with time. Aiding in the tonal aesthetic is the subtle yet enriching score by French pianist Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch. Her compositions turn feelings of detachment and catharsis into auditory sensations and offer a beautiful finishing touch.

There is a quote I heard recently that reads, "Be nicer to your parents, it's their first time experiencing the world too." I couldn't stop thinking about that as I was watching All of Us Strangers. Haigh's emphasis on connection and the complicated human experience, set against a mesmerizing, reality-bending backdrop, is a visual and sensational knockout. At its core, All of Us Strangers is a devastating tale of navigating through grief, and while heartache never feels great, the ability to experience such an emotion is a testament to being alive, which is always something worth being grateful for.

This review is part of our AFI FEST 2023 coverage.