This will be the first film I have reviewed for Cinemacy that I have seen two times before writing a review: first I saw this documentary at the world premiere at Sundance back in January of 2014. Over a year and a half later, I found the film captivating enough that it merited a second viewing, and attended a screening held by LA World Affairs Council leading up to its local release on August 21. With the luxury of having two viewings, here are my thoughts.

Documentaries on social or global issues tend to fall into the trap of emphasizing information in the most conventional way possible instead of using cinematic tools the way narrative filmmakers do to paint the picture. We Come As Friends may be the first documentary film I have seen to entirely emphasize the latter. Opening with a shot of ants crawling on sand amidst a toy airplane, it’s clear that this is going to be a different type of film.

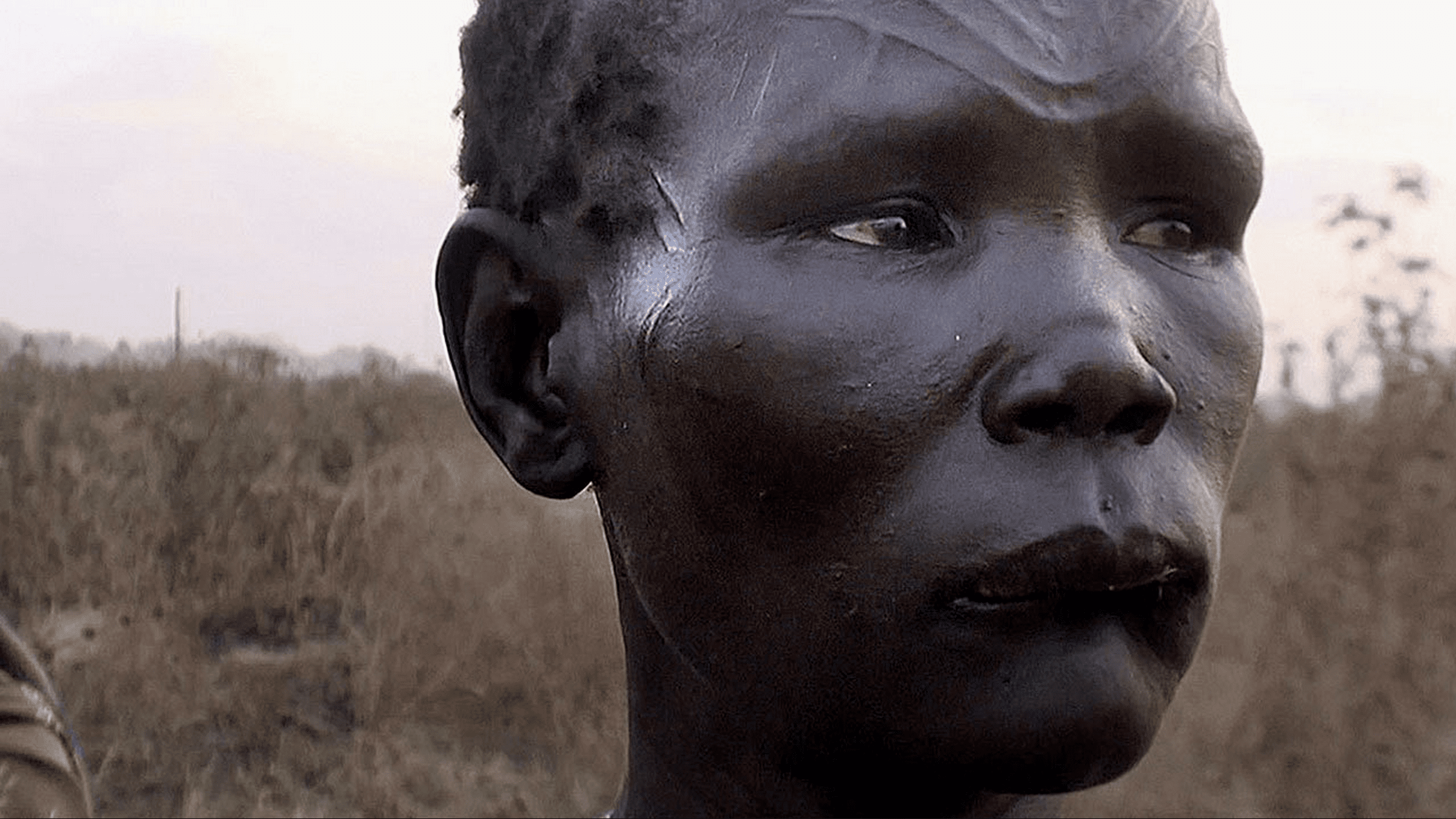

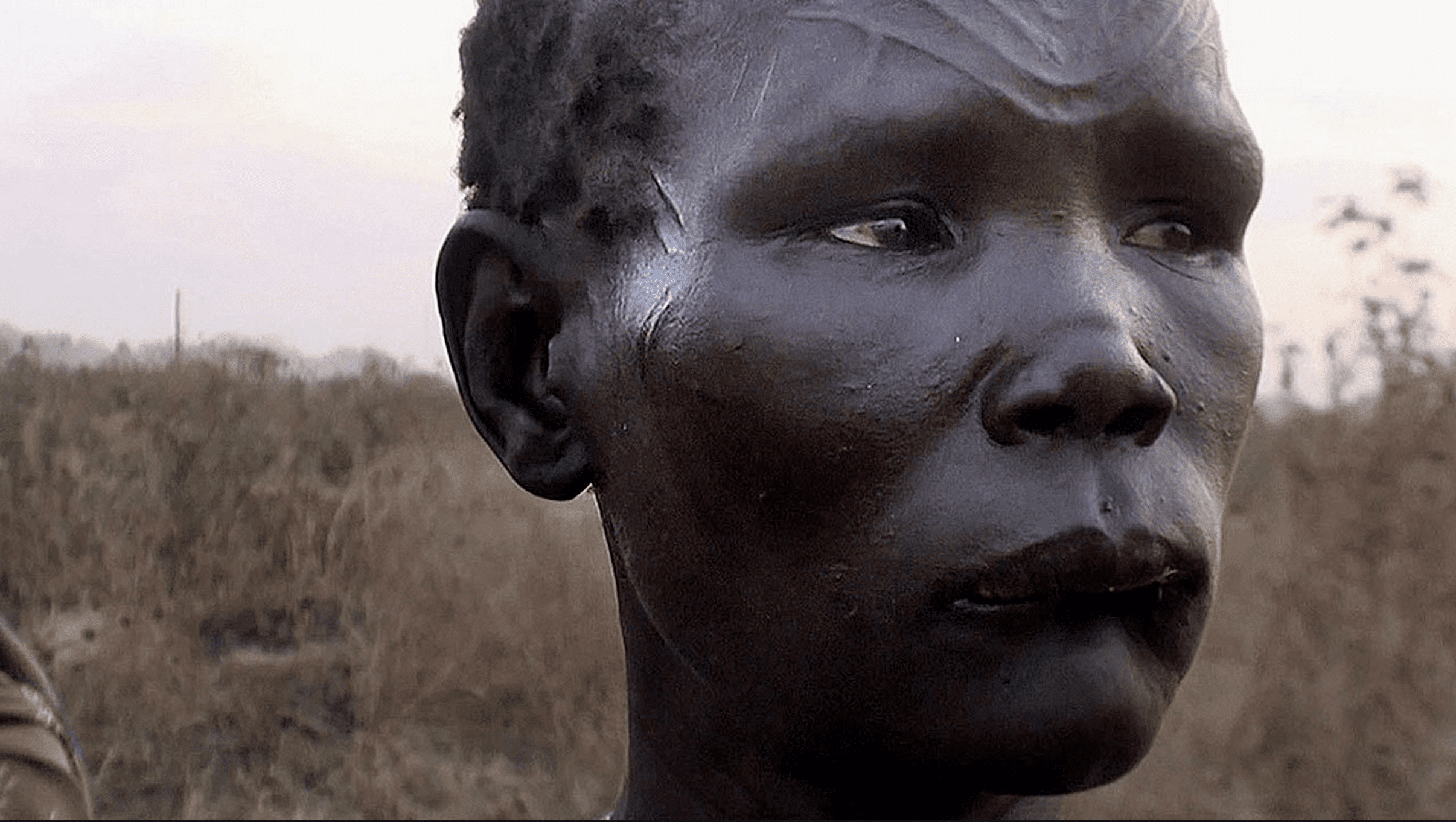

South Sudan is the world’s youngest independent country, and it achieved independence after years of struggle against its Northern neighbor. Now the new country is in a chaotic state without the establishments developed countries take for granted. The result is that a slew of outside forces are intervening with the country to try and make it right in their eyes, each with their own agenda. The title “We Come As Friends” is a reference to these outsiders interference that has had massive consequence on the country, and an allusion to the phrase used to greet aliens in classic science fiction.

Because the results are more thought-provoking and impressionable than a more conventional depiction, I find this to be a worthwhile tradeoff.

Director Hubert Sauper built a tiny airplane to travel from France to South Sudan, as it is challenging to travel through the country any other way. The plane, fittingly named “Sputnik,” was designed specifically for this project. In early aerial shots from the plane, Sauper chooses to film the country upside down, implying that this is a foreign planet. The metaphor of alien invasion is pertinent through the film, as all these invaders seem to treat South Sudan not as a fellow country, but as the colonialists did: a foreign place incapable of independent survival.

Who are these others? The bulk of the runtime is dedicated toward showing all the different intruders and their range of alarming actions: Chinese oil riggers, American Jesus missionaries, Dutch guards, bomb diffusers, and land developers from all over the world. These characters each paint strokes of unnerving reality: every single one is blatantly exploiting the people and the resources of this country. Perhaps what is so insidious is that everyone appears to be happy and thinks they are doing what is right, but what is right for other countries is clearly not what is going to benefit South Sudan. In one sequence, a businessman is cutting the ribbon on a new power plant and shouts to the crowd, “We bringing you light!” as a self-glorifying charitable act. Over and over these foreigners think that they are doing what is best for the country without even giving the people of this country a seat at the table.

Some of the image metaphors are subtle. A quick shot of the Christian family sharing pictures of their house construction shows an image of the house foundation that eerily resembles a cemetery. During a celebration of independence, all of the foreign guards and UN workers are partying, while right next to them are a black South Sudanese waitress and janitor, working. None is more blatant than a Christian American woman trying to put white socks onto a naked toddler’s feet to “help” the child as he cries loudly, not wanting this at all. As I mentioned, because of the vérité artistic style that shows instead of tells, some of these subtle decisions are easy to miss, but the message of neo-colonialism could not be any louder.

Traditional documentaries choose to have crisp sound design for interviews or important moments so that the audience won’t miss a beat. In this film, the sound is often a barrage of background noise: televisions or loudspeakers are often in the background, crowds are never muted, machinery runs at full volume, and yet the film carries on. Not only does this reflect the reality, but it aids the audience to feel just how much of a sensory overload that these exploiting invaders are causing on the indigenous people.

This is an important documentary because South Sudan is a country that the US media has chosen is not worth their time to cover. While most of the footage is now at least 3 years old, the situation has only worsened. Not only is the impact of the film important, but from a documentary filmmaking standpoint, this is one of the bravest and most unique cinematic entries I have encountered. The film does not give an answer as to what to do next. Because of the vérité style, the film doesn’t have the structure often seen as essential. In this way, it mirrors the chaotic and multi-directional challenges that face South Sudan presently. We Come As Friends bears more resemblance to an art piece than to a call to action, which in some ways may be exploiting the country as a means for creating art. A film this radically unconventional runs that risk. Because the results are more thought-provoking and impressionable than a more conventional depiction, I find this to be a worthwhile tradeoff. We Come As Friends is challenging, exhausting, and overall an incredible cinematic experience with stories that otherwise would be ignored. See it as soon as you can.

http://www.wecomeasfriends.com/us/screenings/

We Come As Friends opens at the Laemmle Royal in Los Angeles today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0MgQLk2OCQ

H. Nelson Tracey

Nelson is a film director and editor from Denver based in Los Angeles. In addition to writing for Cinemacy, he has worked on multiple high profile documentaries and curates the YouTube channel "Hint of Film." You can check out more of his work at his website, hnelsontracey.com