Our ‘Wild Indian’ review was first published after the film’s premiere at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival.

In his feature debut, Wild Indian, Indigenous filmmaker Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. commands the big screen with the story of a Native American man, whose trauma-filled past leads to him committing an act of violence that changes multiple lives forever.

What makes the film so powerful is that, beyond it operating as a highly taut thriller, Wild Indian connects it’s present day pain to the larger pain-filled past that Native American people have carried for centuries, making for both an expansive and intimate watch.

A history of Indigenous people’s suffering.

From its start, Wild Indian captures the suffering of Native people, by presenting a title card that reads how man’s sickness was carried west (the connotation of the “western world” being an important note here), as well as the visual of an early Native man in headdress and tribal wear standing over another downed by an arrow, showing a vast history of pain that writer/director Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. connects back to later.

A jump in time brings us to the image of young Makwa (Phoenix Wilson), whose largely silent demeanor hiding behind shaggy hair that often hides the signs of abuse at his father’s hand. Although Makawa is comforted daily by his sensitive friend Ted-O (Julian Gopel), his agitation turns into a quiet anger, which, on one fateful day, results in the senseless killing of a classmate, leaving Makwa and Ted-O with a horrific secret to keep.

A confident vision from an Indigenous director.

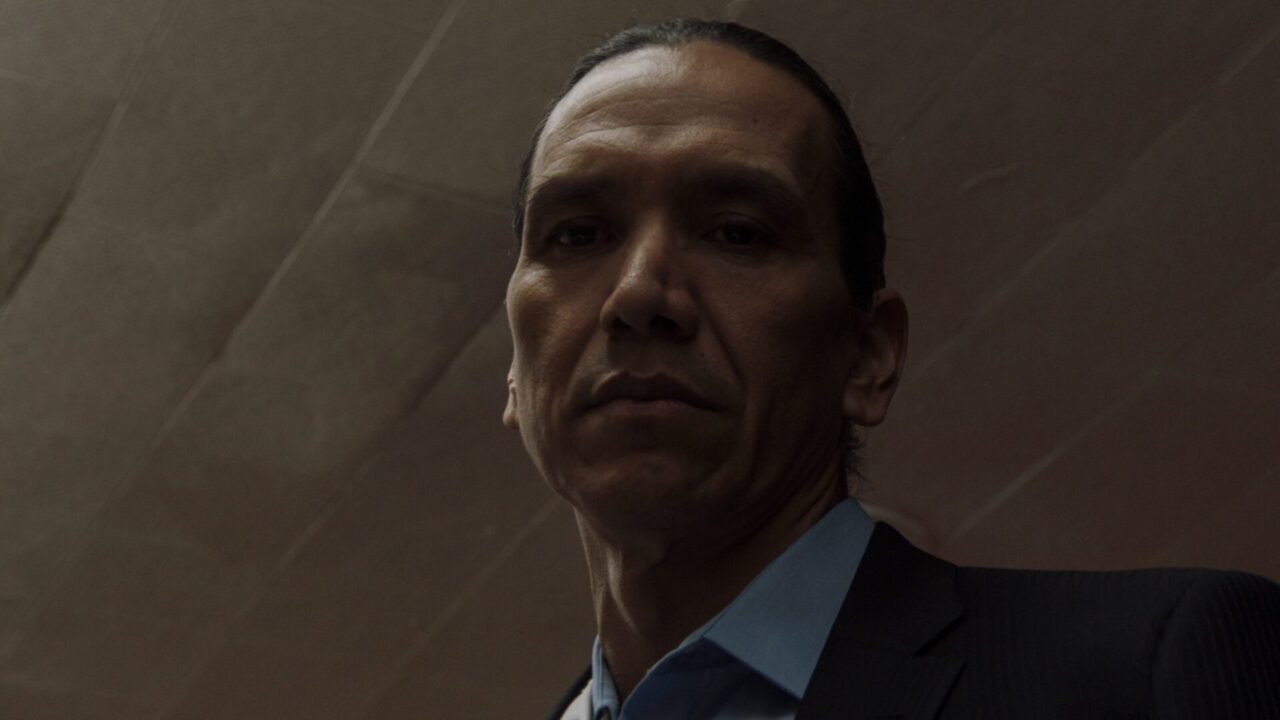

Corbine Jr. makes the confident directorial decision to then leap forward in time over thirty years to 2019, where we see Makwa (Michael Greyeyes)–who now goes by “Michal Peterson”–has succeeded in making a great life for himself, with a white-collar career and partner (Jesse Eisenberg), and wife (Kate Bosworth). Makwa’s fortune impresses the audience, but the real surprise is when we see a grown-up Ted-O (Chaske Spencer), his previously meek, sensitive friend, now covered in face tattoos and being released from prison.

It’s here that Wild Indian puts forward its morality-seeking themes of past sins, and how we are affected by them, as the centerpiece of the film. Considering Makwa’s direct act of committing murder, it’s powerful that the film flips expectations in this way. But Makwa’s repression of his dark past continues to come out in compulsively sick ways, while Ted-O is distraught with the guilt he has carried, forcing the two former friends to each reckon with their past.

Deeply powerful performances.

Wild Indian is cemented by deeply powerful performances by its two leads. Chaske Spencer takes on a scary exterior with face tattoos and a shaved head, but it’s a quiet suffering that makes his character so believable. Greyeyes, with his icy and stone-faced exterior, is able to take on the range of chilling detachment through his eventual crumbling vulnerability. All of this is captured through strong camerawork of gliding sequences and close-up shots to capture the emotions of spirituality and timeless connection, which makes the film feel larger than the frame onscreen.

When all things come to a head for Michael, forcing him to return to his past and leave his new California coast life, the film connects back to its original message of circular patterns of trauma. Wild Indian is a gripping and emotionally charged film that proves powerful both for its thrilling elements as well as its representation of Native culture on the big screen, in substantial roles that we deserve and hope to see more of.

Ryan Rojas

Ryan is the editorial manager of Cinemacy, which he co-runs with his older sister, Morgan. Ryan is a member of the Hollywood Critics Association. Ryan's favorite films include 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Social Network, and The Master.