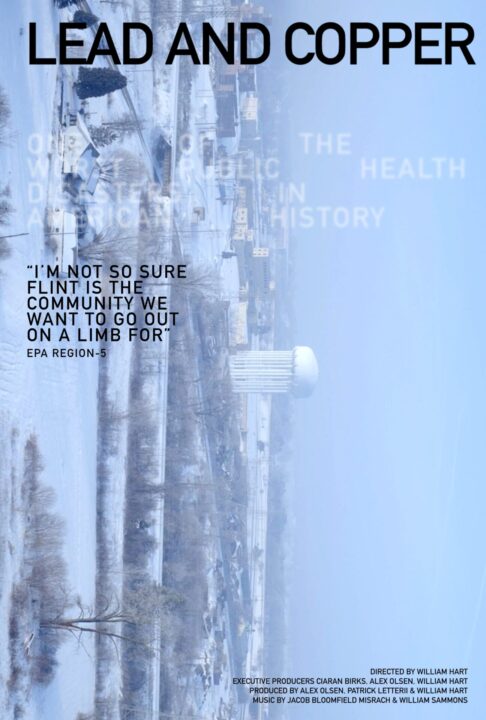

The Flint, Michigan water crisis will forever be remembered as one of the worst public health disasters in American history. The human-created disaster spanned 2014 – 2016 and tens of thousands of lives were forever damaged by their local government’s carelessness and corporate greed. In the documentary Lead and Copper, filmmaker William Hart investigates why Flint officials made the deadly water supply switch in the first place and the severe consequences the community still faces today.

I’d bet that a majority of Americans have never been to Flint, but the opening few minutes of the film do an excellent job of making the audience feel as if we had spent our whole lives there. Sweeping shots of the city, the rolling hills, and robust rivers portray a picturesque community that made up this small but mighty town. All was well in Flint until April 2014, when the city irrationally changed its water supply source from the Detroit-supplied Lake Huron to the Flint River. At the time, Flint residents were paying the highest water bill in the United States at around $230 a month–a shocking statistic that the film lays bare in bold lettering. The local governing officials were becoming fed up with the price gouging and decided to switch to a cheaper, albeit riskier, option. Behind closed doors, it was decided that the municipality water would come from the Flint River, which was meant to be a band-aid, not the solution, to the wider water accessibility issue.

Flint residents familiar with the local river didn’t even want to swim in that water, let alone drink it. Quickly, it became blatantly obvious that the switch was the wrong course of action. The community complained of yellow/brown water that resembled cooking grease pouring out of their faucets. People were getting sick, their hair and skin had become visibly damaged, and that wasn’t even the worst of it. To everyone’s horror, the city was denying there was anything wrong. People turned to buying bottled water in bulk to shower with and wash their dishes. It was unsustainable, costly, and unfair. Eventually, city officials couldn’t deny the issue any longer. These people, under their watch, had been poisoned.

The stories that survivors of the water crisis tell in such detail throughout the film are enough to make you gag in disgust, both at the tainted water they were subjected to as well as their local government. William Hart interviews many people who came to the same conclusion nearly 10 years ago, which is that this happened because Flint officials valued money over human lives. Exposed emails to and from city officials further confirm the theory of turning a blind eye to the lead and copper rules and regulations. The lack of action by those in power signaled that human lives are expendable, especially ones that may run along racial or economic lines.

The film itself is presented in a typical documentary format, including interviews with subjects in their home or business and the inclusion of archival footage from court proceedings and council meetings. The score comes across as a little heavy-handed at times, yet on the whole, the film does an excellent job of recapping the water crisis as well as providing a compelling human interest story about the resilience of the Flint residents. One quote that really struck a chord comes from Elijah Eugene Cummings, the politician and civil rights advocate who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for Maryland’s 7th congressional district from 1996 until his death in 2019. Cummings perfectly sums up the course of thinking that we should all be leading with, especially those in positions of power and influence: “We don’t inherit our environment from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.”

Morgan Rojas

Certified fresh. For disclosure purposes, Morgan currently runs PR at PRETTYBIRD and Ventureland.