'Magnus' Review: This Chess Doc Tells the Story of Young Norwegian Grandmaster

I don’t expect to have even a sliver of the chess knowledge that Magnus has by the end of the film, however, I would much rather watch his games and feel suspense instead of having to wait to be told the answer.

Entering the world of another person’s experience is the gift of a documentary; with billions of people on the planet, there are experiences we will never know or have because they are so different than our own upbringing, and yet watching documentaries is an approachable way to enter another stratosphere. "Magnus," following Norwegian chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen, is one that falls into a wonderful subgenre of docs featuring competitions unfamiliar to outsiders.

These kinds of documentaries can take two directions. The first is that they are made exclusively for those inside the world, and can dive deep into the subject relying on the viewership being already schooled on the subject. Or alternatively, they can serve as an invitation to the outsider, and take someone with less experience and show them how exciting this foreign world is, and by the end of the duration give them something to root for. While both serve purposes in different settings, the latter is generally the more successful documentary that earns accolades amongst critics and viewers alike.

"Magnus," unfortunately, is neither such type and therefore suffers tremendously. First, to a chess insider, the storyline is too basic and surface level to draw much interest. Chess is an insanely complex sport with billions of potential moves, and we’re reminded of its complexity throughout the film but no attempt is made to show it, it is simply told to us. How about for outsiders to the game? Perhaps more egregious is that no effort is made to raise the stakes of any of the games that Magnus plays on his journey. We’re never given any sense of what is going on, and so the only thing to do is wait until the announcer says whether the game is a draw or if he won or lost. Comparable documentaries are successful in building suspense and emotional investment when they clue the viewers into what’s happening. An argument could be made that the games in "Magnus" are too long and complex for this to be possible (personally, I would’ve been more interested in a documentary examining one very intense chess game than glossing over a dozen without any explanation). This film may inspire chess players in the same way we’re told Magnus has inspired young people who are familiar with him, however, I would need to go home and read more about Magnus in order to be inspired by his prowess.

Eagle-eyed readers may remember that I made a very similar critique of the last chess film I saw, "Pawn Sacrifice." In that film as well, no attempt is made to clue the audience into any of the games of chess shown. Both films briefly show fancy graphics making seemingly meaningless gestures over the game board. All that does is alienate the viewer further. I don’t expect to have even a sliver of the chess knowledge that Magnus has by the end of the film, however, I would much rather watch his games and feel suspense instead of having to wait to be told the answer. The lack of effort in making the chess games interesting makes a documentary focused entirely on the game practically unwatchable.

A counter-point would be that the film is intended to be about Magnus himself beyond the game. Thanks to a good supply of archival footage, there is an attempt to show his upbringing and family life. Yet the movie falls into the same problem: we’re told in interviews about how Magnus was an outsider or is bullied, and yet visually there is little to engage these messages. Even from a young age, it’s clear he is destined to be a savant, yet the transformation to chess master feels madly rushed from humbly playing at home, to being ranked in the top 1,000 and taking on the #1 player. I’m told multiple times he is the Mozart of chess, and yet without concrete reasons as to why he plays so well, it’s lost on the viewer.

There is plenty of emotional potential in any film focused on competition at the top level. This is why sports documentaries and even narrative films can engage viewers regardless of if they know the outcome. I would’ve liked to finish the film having extreme admiration for the accomplishments of this clearly brilliant individual, and yet the lack of insight into his world left me cold. By being unwelcoming to the outsider and uninteresting to the insider, Magnus does a major disservice to the brilliant young man for whom it takes its name.

"Magnus" is not rated. 78 minutes. Now playing at the Laemmle Music Hall and streaming on VOD.

'Into the Inferno' Review: A Different Kind of Nature Odyssey

Some view them as gods, some as ancestors, some as government. But the action of exalting is found globally.

In director Werner Herzog’s own words, “This is not something you will find playing on the National Geographic channel.” And will all due respect to NatGeo, from the very beginning, with the sounds of an angelic chorus singing hymns over images of a fiery chasm of volcanic magma, we know we’re in for a different kind of nature odyssey. Over the next 100 minutes, we follow Werner Herzog and volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer all over the globe as they witness some of the world’s most deadly volcanoes and the people nearby who call the land adjacent, home, in "Into the Inferno."

About halfway through the movie, I had a realization that completely invigorated the remainder of the film’s runtime: Herzog has no intention of making a movie about volcanoes and their properties. Again, let’s leave that to the educational documentaries. This is hardly a film about volcanoes at all, it is, in fact, a story of humanity. Herzog’s journey is about humankind’s relationship to these fiery infernos, and how that varies from place to place worldwide. These chasms have produced legends of all kinds that vary whether he is in the South Pacific, Antarctica, the Caribbean, or most surprisingly, North Korea. The myths themselves are intriguing, but the heart of the film is the power that these volcanoes strike into the hearts of those who witness them up close. Some view them as gods, some as ancestors, some as government. But the action of exalting is found globally. So, when the film makes a detour to talk about the beginning of civilization, while I was initially puzzled, I recognized it as a way to confirm the focus on humanity, despite being led to believe it’s all about the volcanoes.

This type of bait-and-switch artistry is what makes Herzog so essential to the documentary world. He playfully rejects the notions we have grown accustomed to of the informational documentary and views the medium more as art than educational think-piece. This demands an extra level of attention from the viewer, but for cinephiles, this is a delightful treat to the stimuli. My personal realization that he had in fact made a movie about humanity disguised as a volcano film is the type of exciting realization that makes this engaging, and I wouldn’t be surprised if another viewer read into an entirely different argument, in fact, I’d welcome it.

Finally, unlike many films released in the fall which only get specialty releases in the major cities, "Into the Inferno" is already available to view on Netflix! In other words, there is no need to wait another moment to dive into this adventure. Let the ferocity of the world’s volcanoes matched with the insight of a documentary master be your companions on your next night in.

'Into the Inferno' is not rated. 104 minutes. Now streaming on Netflix.

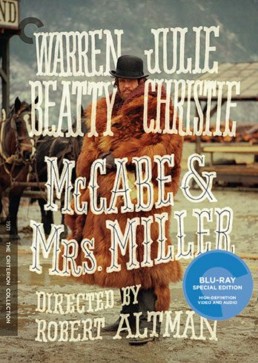

Robert Altman's 'McCabe & Mrs. Miller' Comes to Criterion Collection

In conjunction with The Criterion Collection’s latest release, the Aero Theater hosted a double bill screening of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) and a documentary about its cinematographer No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo and Vilmos (2009). Screening these two entries together in a crowded theater of cinephiles (including members of the Altman family) was an excellent way to express the spirit and mission of The Criterion Collection as one of the few companies focused on preserving film for future generations. McCabe & Mrs. Miller is the most recent addition to the Criterion catalog, and here is some insight as to why the 1971 film is worth a revisit today.

Warren Beatty and Julie Christie play the titular McCabe & Mrs. Miller, respectively. In an early 1900s frontier mining village in the Pacific Northwest, McCabe, a flawed businessman, attempts to build a brothel to make money off of the nearly all men town (ironically named Presbyterian Church). He crosses paths with the British prostitute Mrs. Miller, who quickly intervenes and says that if he’s starting a whore house then she is to be his partner. McCabe, much to his chagrin, is persuaded into agreeing. The unlikely partners develop their ambitious goals as a frontier village slowly builds around them, with a colorful cast of miners, outlaws, prostitutes, and other townspeople all brave enough to endure this harsh American landscape.

Amongst the auteur-loving crowd, Robert Altman stands shoulder to shoulder with Coppola or Scorsese. One of his signatures is his masterful use of ensemble casts, and McCabe is surprisingly another incredible display of this talent. Sure, Gosford Park (2001), Short Cuts (1993), and Nashville (1975) boast more star-studded ensembles, but in this film, every single member of the small frontier town are utilized and developed. There are no ‘extras’ here: the townspeople are funny, endearing, and given storylines that play out in full. In the film’s climax, the nuanced development of the entire ensemble pays off as Altman stages a sequence that employs the entire town in a thrilling, unforgettable conclusion to the movie.

It’s worth emphasizing the importance of this new restoration as a way of keeping this film in the utmost quality it was meant to be viewed as. One of the treats of this double feature was after seeing the restoration, I saw clips of the pre-restoration version in the documentary, which was released in 2009. The difference is stunning: shots beforehand are muted and darker shades blend together, whereas in the restoration everything pops and the intentionality of DP Vilmos Zsigmond is on display.

Seeing the movie in theaters instead of on the Criterion disc meant I won’t be able to review any of the supplemental material, but the screening introduction by documentarian James Chressanthis included memorable anecdotes and insights into the film’s creation. On the note of cinematography, Altman and DP Zsigmond were both fed up with the oversaturated Technicolor look of Hollywood that was at the time the norm, so instead opted for a muddy, grainy look to establish the rough frontier town and the grit that came with it. When the studio received the dailies, they were horrified at the results. Altman reassured them that the Vancouver lab where the temp prints were being made (the film was shot in British Columbia) was not up-to-par and that the negatives would be just fine. He was, of course, fooling them and continued to shoot in this style so by the time they were done the studio had no choice but to release the film as such. This rebellious photography is still gorgeous in its own right and more importantly utilizes the visuals to convey the story at hand, always a mark of a master DP.

Between the aforementioned photography, beautifully matched songs by Leonard Cohen, and two memorable performances from the leads, this film holds up as an essential example of American cinema at a time when the film industry was reaching a cultural explosion. For classic movie aficionados and casual moviegoers alike, there is much to be savored from the Criterion’s latest entry.

Review: Wrongfully Convicted Women Await Justice in 'Southwest of Salem'

Despite intentions of equality and fair judgment, our country’s criminal law system is still not evenly balanced. Headlines of the infamous Brock Turner case (and specifically, the biased judge who essentially let him off the hook) only reaffirm this sentiment. Unfortunately, while it seems like many seem to skate through imperfection with minimal damage, in this case, it’s determining the outcome of people’s lives, and the errors from both judge and jury have massive ramifications.

Such is the story of Southwest of Salem, director Deborah Esquenazi’s documentary following the story of the “San Antonio Four.” It's not surprising if you haven't heard about this case before, while it garnered some local attention, it certainly isn’t as present in the zeitgeist as other trials. However, after watching the film, it’s impossible to forget this story. The San Antonio Four are four Latina lesbian women who were wrongly convicted of sexual assault and related deviant behavior on two minors, despite being 100% innocent.

The story begins in the 1990s, and it’s amazing to think of how far the world’s understanding of the LGBT community has come since then. For these women, being a lesbian is a radical stance in their community, and this sadly leads to the horrific accusation that ignites the story. Using home videos and interviews, we get to know these women extensively and how much they go through from the turn of the century until present day. When we first meet them, they are all loving, family women who have been strong mothers or maternal figures, and have built a tight-knit love and friendship with each other. It’s all the more painful to see these young women, who we see are good people from the home videos, have their entire lives flipped due to a prejudice-charged accusation. Doing prison time for a crime they didn’t commit sounds like something only found in fiction, but here we see each of them experience the trauma of prison purely due to accusation. At the emotional center of the film is Anna, one of the four women who serves as a protagonist and becomes the primary voice for justice. Her confident articulation of the events allow us to understand exactly what happened and to get some sense of the amount of pain she and the other three women have had to endure.

While the film is almost entirely focused just on this case, it briefly opens up to acknowledge a few other cases where the bias of those in authority allowed for innocent people to be locked up. It’s unfortunately not as much of a rarity as you’d hope. The primary biases displayed are sexual orientation and race. Fortunately, there are a handful of good people out there who are fighting to amend these situations, and in this film we get to see a few of those who took a stand for the San Antonio Four.

The trajectory of the film indicates that by the time you’re finished watching, all will be resolved and after years of hardship, justice will be served. Unfortunately, this is not the case, and the film is a rare example of a story in progress. Media attention can win cases, and the film has a powerful agenda to get the word out there and build solidarity for these women. It’s evocative to see a documentary being used for such a cause, rather than many which end with a neatly wrapped up story. Both have their place depending on the subject. For this one, I invite you to witness the story of the San Antonio Four, and help develop a larger public awareness that will allow the story to reach the moral conclusion that these individuals deserve.

'Southwest of Salem' is not rated. 91 minutes. Opening at the Laemmle Music Hall this Friday, September 30th.

Kirsten Johnson Talks the Art of Returning in 'Cameraperson'

You may recognize cinematographer Kirsten Johnson's work from any of her 45 credited IMDb films, including "Citizenfour," "Very Semi-Serious," and "The Invisible War" to name a few. "Cameraperson" marks her directorial debut and has been making waves on the film festival circuit ever since its premiere earlier this year. This multiple award-winning film about love, loss, and the human connection may be Johnson's first, but let's hope it's not her last. In our interview, we talk about improvisation on the job, the hard truth about missing shots, and the two things you must know before taking on the role as a cameraperson. We begin:

How did this film originate?

What is peculiar about the process of this film is that it emerged out of a completely different film that I worked on for three years, set in Afghanistan. When I completed that edit, a young Afghan woman who was in the film said, 'I'm sorry, I don't feel safe [being exposed].' From that point forward, we began trying to imagine how we could re-cut the film without her face in it. That edit went to Sundance through the composer's lab and the editor's lab. At the editor's lab, people thought the film didn't work. Then in one conversation, I told the story of how a truck dragged [a man] to his death and everybody really connected to that story. Suddenly we had almost the complete inverse idea, to use only Afghanistan visuals with me telling the story of other places on top of it... Then it became, 'What if the material just speaks for itself.' I think that decision to choose that restraint is the most important part of what makes the film function. It's kind of incredible, how one works through ideas.

Was there ever a time when you felt like you shouldn't be documenting a situation you found yourself in?

Yes, many times! You're always in these moments where people are exposing such intimate things and sometimes people don't realize what the consequences might be for them. I come from a generation of documentarians who existed before the internet when we believed we could promise people we could control the images. We all now know that is not the case. That's the challenge- it may even be that you feel fine with what you're doing in the moment, but then sometime in the future you realize the choice to be there with the camera was naive or exploitive.

"It's kind of incredible, how one works through ideas."

Because you've had time to film and acquire all of these moments, it's like you have this advantage to take a step back and see the bigger picture, whereas typical documentaries are shot for a contained amount of time. I think that's one of the reasons why the film is so impactful.

Yeah, it's not like I'm making a retrospective of my great career– no. It's that I have accumulated a quantity of questions that I have seen duplicated in many places, and I have experienced it over and over again. I have enough material to make these questions public.

One of the themes that I really enjoyed is this concept of returning, both editorially and literally.

Aww! What I'm learning about this process is that something different matters to everyone, things that I haven't even thought of. I haven't been speaking of "return" as a fundamental idea of the film, but it totally is. Thank you! In my line of work, the capacity to return is limited. I get hired to go to a place with a relationship that the director has created, and I'm not at liberty to just return somewhere because I love being with those people. I couldn't do that as a camera person, but I was always seeking to address the things left undone.

Do you struggle with setting up "the perfect shot" vs capturing moments on the fly?

Improvisation is the first mode, you can't know [what you're shooting] in advance. Even if you're working on a film that uses a tripod and all of the shots are locked up, the impulse is primarily an improvised one. You have to be ready, and you also have to accept how much you'll miss.

"You have to be ready, and you also have to accept how much you'll miss."

Oh, that's interesting.

I think you must miss so much to be fully engaged in the project. Managing that anger or frustration itself while you're shooting is constant. Also, if you've been consistently trying to make strong aesthetic decisions with your film and trying to frame things beautifully, and then something that comes out of left field is framed radically different, in some ways that signals to the viewer that people were out of control in that moment. I think we all agree that is where the most interesting emotion of human interaction happens– when people are out of control.

You've been showing this film for over 9 months, how has Cameraperson generally been received?

I've been overwhelmed by how beautifully it's been received. One of the really gratifying things for me is that [in the beginning], a lot of people told me that only filmmakers would be interested in this film– and that is not true. It's gratifying that people with no relation to documentary films, other than the fact that they are viewers, embrace it. The thing I love is that really young people love it too!

Have you shown this film to the people in it?

I'm hopeful that [I will find] as many as people as possible that were in the film and return to them. That would be amazing.

"One of the most important things you need to know as a cameraperson is that you can't be dehydrated and you can't go to the bathroom."

For filmmakers beginning their documentarian journey, what practical advice would you give?

You don't know what's going to happen and you may have to keep filming for hours on end, so one of the most important things you need to know as a cameraperson is that you can't be dehydrated and you can't go to the bathroom. You have to actually know how much water you need to drink to stay hydrated and not go to the bathroom. This is the best advice I can give anybody! I can shoot for 14 hours straight without having to go to the bathroom. If you have the capacity of being relaxed in your own body and to respond emotionally to what your filming, then you can do it. If you're tense or preoccupied in your body by whatever your physical restraints are, you cannot film the scene.

'Landfill Harmonic' Finds Beauty in a Place Most of the World Would Dismiss

The joy of non-fiction stories is that they can be as incredible as ever without giving the viewer skepticism like they would if a screenwriter had conceived it. Landfill Harmonic is an inspiring documentary about impoverished children who live in a garbage-filled outskirt in the capital city of Paraguay and their inventive way of getting past their circumstances.

A local trash collector named Colá starts making musical instruments out of the trash he finds. An environmentalist is sent to this town to help alleviate the unfixable trash problem but instead discovers a musical solution. Together these two community leaders take a group of schoolchildren and form “The Recycled Orchestra.” By making instruments out of trash, it gives them an opportunity to play music on instruments they could never otherwise afford, like violins and cellos. The result is a story that caught on like wildfire and allowed these children to become more well-known than they could’ve ever dreamed.

This is a story worth sharing in large part because of the intersection of many global problems that it connects: musical culture, environmentalism and waste, education to the impoverished, and more. The hook of seeing children learn music on instruments made of recycled garbage is an entrance into a community we otherwise would never imagine here in the US. It is stories like these that help bridge the world and build a collective understanding of communities across continents and nations.

There is nothing but exuberant praise to be given when discussing this film’s story. Unfortunately, the documentary upon which it is built does not always allow this premise to shine as brightly as it potentially could. The major issue is that there is a clear rift between the two central stories: the music and the trash-ridden community. Playing these instruments has given these musicians the opportunity to travel worldwide and share the power of their story. However, it’s never seen as a way to empower them upon returning home. All I saw was a major disconnect between getting to travel and play for other nations, and then returning home to the same situation as before. What would have been more impactful is showing a connection between their current situation and the long-term change for good that their music is creating. Otherwise, I fear the recycled orchestra comes across as more of a sideshow to the more affluent parts of the world. When the film builds to big moments, for example when the students are playing concerts, it doesn’t capture the power that the music is having on these kids as much as I imagine it would. The approach feels a little more like an outside perspective, whereas I would’ve preferred a clear direction as to where the narrative is going and how the characters are feeling toward the extraordinary situations they reach.

That being said, one message is clear: you can’t expect the people at the receiving end of a trash-producing world to be the ones to fix the problem. We all need to reduce waste drastically and the images in the film confirm this. How to do this on an impactful scale is a question I’d still like to see an answer to. I find that this film is a great introduction to the story but not as in-depth of an experience as many contemporary documentaries. At least there is no doubt that these young musicians have found hope and beauty in a place most of the world would easily dismiss.

"Landfill Harmonic" is not rated. 84 minutes. Opening at the Laemmle in Santa Monica on Friday, September 23rd.

'Cameraperson' is a Masterful Dive Into the Human Experience

When analyzing a film, two primary forces determine its quality. First, is how effective the emotional reaction is, as this is the foremost reason as to why we go to the movies. Second, is what the film does cinematically to achieve this goal. The excellent films are those that are able to push boundaries and try new things that work in ways we’ve never seen before. "Cameraperson" is such a film. It opens with a quick text describing what we’re about to see: director Kirsten Johnson has been a camera operator and cinematographer for 25 years, and in this documentary she has compiled a series of footage that she has shot, then edited it together as a memoir of her experience in this role. The result is an experimental project that pushes the potential of filmmaking and non-fiction storytelling to new heights, and a dive into something wholly unique.

From the get-go, she makes it extremely clear that there is an active human being behind the camera. In a conventional film, the artists are invisible and viewers are meant to forget the behind-the-scenes. This film starts out raw to expose the layer behind which our storyteller is operating. We see the parts that are usually omitted from a polished film, and through this, we gain an understanding of who the cameraperson is as an artist. Pulling clips from over 20 films, we then follow Kirsten Johnson and her camera all over the world: Bosnia, New York, Sudan, Yemen, Liberia, and more.

You can recognize that these images are pulled from the context of other stories, often of mass conflict and sometimes tragedy, but here Johnson uses them to tell a biographical story of her own, while at the same time miraculously covering the human condition as a whole. When two outwardly different clips are juxtaposed together, a larger narrative unfolds. Because of the sheer vastness of sources she’s pulling from, as a viewer you can feel that everything we see on screen has been deliberately put in this order to achieve a certain effect. Nothing feels out of place, and the entire runtime feels masterfully compiled.

The effect it achieves is absolutely stunning: we witness life of all forms and see universal themes everywhere. Traditionally, documentary and narrative films are made using material created in a relatively short amount of time: this film has the luxury of being able to take a step back and see the macro picture created in the filmmaker’s entire body of work, and what it means to her. The role of a “cameraperson” is one that nearly everyone inhabits daily in today’s world, and this film exposes the tribulations of when to film and what to film, questions that we all are used to deciding regularly. Our director may be a professional, but the work she does is relatable to anyone who’s ever hit record on a device and let it run.

While also giving us a taste of her career and an admiration for what she’s done, Johnson explores a handful of recurring motifs that she’s found in the world, entirely about the human condition but within that is an infinite number of themes. She never outwardly says what these are, but the editing does this for us. The story of a young mother in Alabama that the director filmed is powerful on its own, but when followed by footage of the director’s own mother, the results are exponentially more effective in ways I’ve never seen film achieve.

One of my favorite motifs that the film makes is the idea of returning somewhere. This works twofold: sometimes in the film’s editing we’ll return back to a clip we’ve previously seen and it has another meaning given the other footage shown in between. On a more literal level, there are moments where the cameraperson returns to a location she’s been to after a period of time, something we all begin to experience more often as we grow older, and the effect is profound.

Because "Cameraperson" covers so much ground, goes so many locations, and causes so many emotional reactions, it’s densely packed to the point it feels like you’ve watched an entire series of films by the time you’re done. That’s a high compliment: it’s a pure feast of filmmaking that left me with the same fulfillment I’d get from watching 20 different documentaries.

The film is so dense that even though I saw it back in January at Sundance, I knew I’d need to see it again and found even more moments that stayed with me: its density means it’s hard to keep track of it all mentally, but this is the type of film that could easily invite a revisit. Given its experimental nature, it’s also easy to find more details upon a repeat viewing.

As a fan of film and its potential for personal impact, rarely has one so powerfully achieved so much. Unconventional movies generally are more alienating to viewers, but this one is the opposite: it’s an invitation to dive into the human experience, through the lens of one individual whose seen so much life around the world.

Few movies have done so much for me as a viewer and achieved new heights in the emotional and cinematic experiences that I seek out. I reiterate that this is one that can’t be missed, at the very least because it’s one I can’t wait to discuss with people as they see it for themselves. Extremely personal and simultaneously universal, "Cameraperson" is one of this year’s most essential cinematic achievements and a formidable contender for one of the best films of the year.

'Cameraperson' is not rated. 102 minutes. In theaters on Friday.

'Pete's Dragon' is What the Family Movie Can and Should Be – Magical

It’s a travesty that the description ‘family movie’ has been marooned by studios and the public alike as a juvenile and tasteless affair. Animated movies aside, the subgenre is no longer seen for its potential: to enrich the lives of all those who watch it, provide a nourishing dose of spectacle to the wide-eyed young audiences and sincere delight to the parents and older folks that accompany them.

"Pete’s Dragon," opening nationwide tomorrow and the latest of Disney’s live-action remakes, has exactly that type of magic that’s been devoid at the cineplexes. I admittedly haven’t seen the original, one of Disney’s less-branded properties, so can only speak about how the current film stands. The title is a reference to our protagonist, Pete (Oakes Fegley), an orphaned boy who lives deep in the woods, alone with the green dragon, and for years has avoided human companionship. I expected the film to wait a long time to reveal the titular dragon as most movies would, but instead he’s introduced and shown right from the get-go, a nice device that reminds us this is their story, not the story of the outsider townspeople we’ll meet next. The dragon is shown early but its enchantment continually develops as stakes are raised. This introduction works as a way to immediately put us on our protagonist’s side: while the outsiders nearby don’t believe in such creatures, we as an audience do.

These outsiders are a well-cast ensemble of familiar actors, all living in small town U.S.A. Bryce Dallas Howard is Grace, the no-nonsense forest ranger who’s never seen a dragon. Her fiancé Jack (Wes Bentley) and brother-in-law Gavin (Karl Urban) are loggers encroaching upon the forest. Oona Laurence plays Jack’s daughter, Natalie, and continues to prove herself as one of the greatest current working child actors in this touching supporting performance. Lastly, the legend Robert Redford plays Grace’s wise father, Meacham, who shares the movies wisdom with a reverence that can only come from cinema’s finest in a role that likely was tailor-fitted to him.

Aside from Bentley’s character, who we don’t get too much of, this ensemble all shine in their respective roles, and each one is given the opportunity to grow as a character thanks to the adventure they’ll experience. There’s no need for crude humor or pandering kid jokes, our characters make the story come alive without lowering the bar. Time and time again the film respects our intelligence as viewers and develops with a certain grace that never takes us out of the story. It’s amazing that something simple and well-executed feels like a marvelous revelation in this case, but regardless I’m happy to have experienced it here.

I’m impressed at how easily the film could have diverted into overused tropes but doesn’t. From the moment the protagonists are established as loggers and rangers, I was waiting for the inevitable heavy-handed environmental message that always feels hypocritical coming from a major studio. As we learn more about Pete, I was ready for a certain orphan backstory that you’ll think has to be employed. But the film is above all that, it never succumbs to the on-the-nose mentality. Instead, these themes of wilderness/nature and mankind’s interference stay subdued knowing that within the context, all audiences are mature enough to understand what’s at stake.

And most of all, this is a beautiful story about what it means to grow up, perhaps the perfect theme for the genre. There’s even a feeling reminiscent of Room, one of last year’s finest entries, in the protagonist who similarly enters society for the first time, and the rest of us can relate to the emotion of life changing fast and taking on the new feelings while holding dear to the past. Rarely can a movie so smoothly depict an easily comprehensible storyline while also layering in meaningful themes to be understood differently by the many age groups who may all relate to varied experiences.

And on another note, only because I can speak about it, the 3D in this movie does no noticeable enhancing, so it isn’t worth the extra upcharge. The movie works great on its own, and I invite readers of all ages and interests to experience this treat; check your cynicism at the door and let the movie’s wonder and magic take you as it did for me.

At a time when both the world at large and my own personal experience feel like widespread compassion is shortchanged, "Pete's Dragon" is an adventurous and triumphant return to those joyous feelings that make the world feel like a better place. Let this film serve as a benchmark for what a family movie can and should be: an emotional embrace of heartwarming adventure from start to finish.

"Pete's Dragon" is rated PG for action, peril, and brief language. 102 minutes. In theaters nationwide tomorrow.