In 2013, Steve Hoover’s directorial debut Blood Brother premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it went on to win the U.S. Documentary Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award. Blood Brother tells the story of American humanitarian Rocky Braat who traveled to a poverty-stricken, HIV-infected orphanage in India determined to give the children a sense of family that they, and himself never had. Now, Hoover is back with another social justice documentary with an even darker tone in Almost Holy, which profiles local Ukrainian pastor Gennadiy Mokhnenko who, unlike Braat, only has to turn to his own backyard to singlehandedly try to solve the rise of homeless and drug-addicted kids.

The film begins in 2012 in the Pilgrim Republic, a children’s rehab center started by Gennadiy, and right away we are thrust into the chaotic and messy reality for all who stay there. Children as young as seven and eight have track marks on their tiny, frail arms from heroin, others are dying of blood infections. Most are orphans and those who do have living parents have lost them to a lifestyle consumed by alcohol and drugs. It is a terrible sight made worse by the fact that even earnest attempts to help the children don’t cut it. Ambulances are equipt with just bench seats, no oxygen, nor electrical life-saving devices to speak of. Despite all of these odds stacked against him, pastor Gennadiy has bravely committed his life to end child homelessness by any means necessary.

Gennadiy, speaking to the camera in broken English, explains that since the breakout of the Soviet Union, there has been an exponential problem with children living on the streets and in manholes. His tireless efforts are seen during night raids, where Gennadiy and a small team forcibly abduct street kids and take them to the Pilgrim Republic. We watch as desperate children crawl out from trash piles and broken down cars, sewer pipes and gutter shacks. They are transported to the center and given a meal, a shower, and a fresh start. Gennadiy’s hope is that these children will get adopted out to loving families. His ultimate goal? To shut down the Pilgrim Republic, to have no use for it anymore. Essentially, to solve the problem of child homelessness in Ukraine.

There are many people who consider him a folk hero, however, he faces adversity from those who call him a “lawless vigilante.” He explains that the common attitude toward the issue is “it’s not my problem,” and so he takes it upon himself to intervene in a kid’s dangerous, and potentially deadly, lifestyle. “If I don’t,” he says with sorrow, “who else will?”

Let me reiterate the intensity of the film by saying this: I watched Almost Holy while eating lunch, and some of the scenes were so intense and explicit, I literally lost my appetite (and ended up tossing my half-eaten chicken breast in the trash). Hoover managed to hook and pull me into the dismal and dark streets of Ukraine so vividly, it is fully captivating. As a filmmaker, that is a wonderful feat– to affect audiences so much that they have a visceral reaction to what they’re watching on screen. As a human being, however, it is a hard thing to witness.

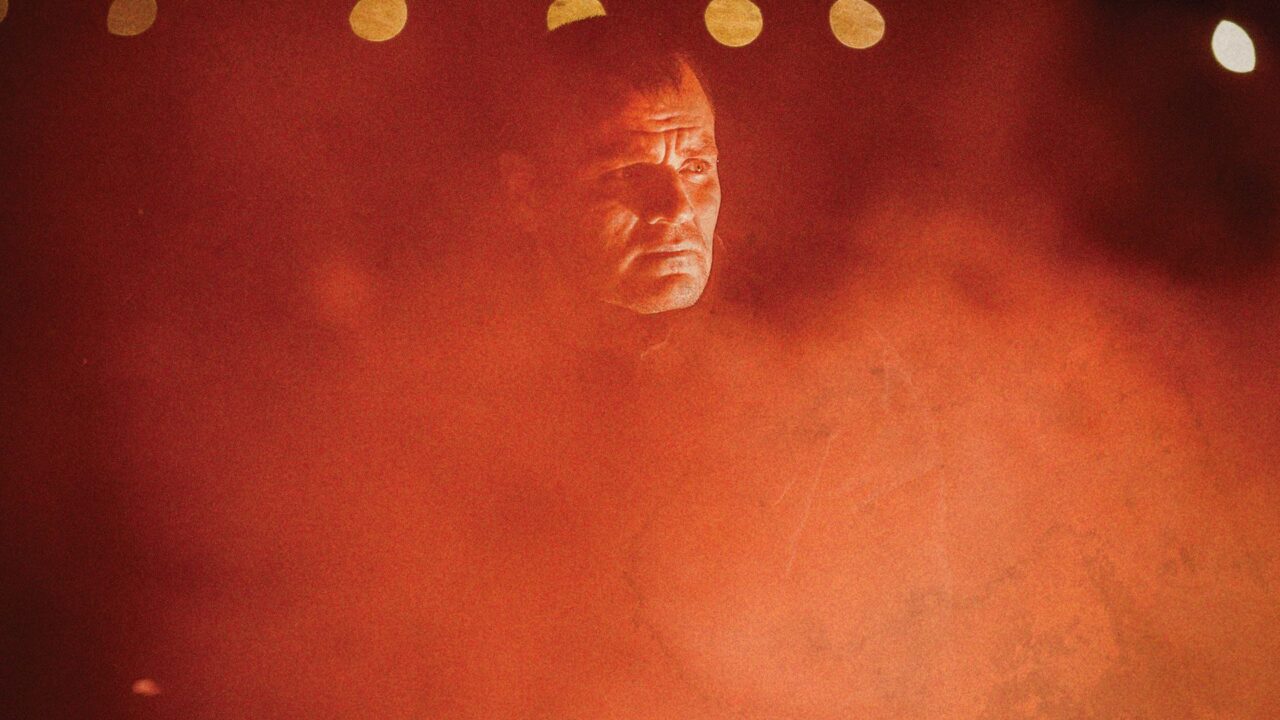

Almost Holy, executive produced by Terrence Malik and with a powerful score by Atticus Ross, is a stunning cinematic portrayal of one man’s mission to save, but it is hard to stomach (literally). The message is important and Gennadiy is a fantastic narrator, his passion for the children is extremely affecting. Before you watch Almost Holy (which I recommend you do), be mentally prepared for a vivid and raw viewing experience. Personally for me, great films linger in my mind for days after viewing and this is definitely one of those films.

Almost Holy is rated R for disturbing content involving drugs and alcohol, sexual references and language. Opens at the Sundance Sunset on Friday, 5/20 and nationwide 5/27.

Morgan Rojas

Certified fresh. For disclosure purposes, Morgan currently runs PR at PRETTYBIRD and Ventureland.