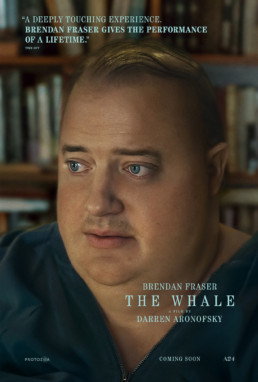

The Whale

Brendan Fraser stars as a recluse battling obesity in Darren Aronofsky's 'The Whale,' a powerfully affecting tale for our times.

The first thing you’ll notice in Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale is its unexpectedly compact format. With a screen ratio of 1.33:1, the frame is nearly square on all sides. Intriguingly, there won’t be any extra width for this story.

As the opening title credits began, seeing this already made me feel uneasy. I, like anyone who will be going into this movie, knew that the central character is an extremely obese man. How then, will he fit into this screen for the remainder of the film?

This (intentional) visual restriction immediately sets the stage for a story of discomfort, pain, and struggles to come. As soon as we see Charlie (Brendan Fraser)–by way of an uncomfortably shocking introduction (in many carnal ways)–we see how enormous, and helpless, a figure he is. We know instantly how impossible it must be for him to exist and fit into the world around him.

Except, we quickly see that he doesn’t actually exist in the world. Rather, as today’s 21st-century accommodations allow, he lives in his own reclusive world; inside, and alone. Teaching an online writing class (one in which his camera remains off), he spends his days either occupying the same flattened corner of his living room couch or traversing the path between his bedroom and bathroom, by way of a walker whose flimsy frame feels as if it could fold under his weight at any moment.

With over 600 pounds of body mass, Charlie is a sight to behold (I say this with no intention of sounding insensitive to the obese community). Yes, Charlie’s appearance is shocking, which the film presents starkly. Yet, the film as we see it is one of empathy. Director Darren Aronofsky’s singular achievement here is how he draws out the sweet, kind, and tender soul of the man underneath the heavy flesh.

Undergoing an immediate health complication that begins the film, Charlie’s nurse and friend Liz (Hong Chau) tells him that he’s in grave danger of dying. The episode brings about a forced introspection, one in which he decides to attempt to reconcile with the daughter he left behind years ago (you would be correct in remembering Aronokfsky’s other film about guilt by way of fatherly abandonment, 2008’s The Wrestler, here too).

We see each day of this final week, with title cards to count them down. Not coincidentally, this narrative structure should also recall the biblical story of creation, in which God created the universe in seven days (we all know what he did on the seventh). Religion and man’s relationship with it, and faith and higher powers at large, are always a preoccupation in Aronofsky’s films, as it is here too. The film confronts religion by way of a young door-to-door missionary (Ty Simpkins) who befriends Charlie and tries to save him by converting him before the rapturous end times (which are closer for Charlie than the young missionary knows).

The central story in The Whale is that of Charlie reconnecting with his daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink), a high schooler whose troubling social media accounts reflect her raging, isolated nature. Drawing her to his home, Ellie sees her father for the first time in years–more enormous now than ever. Her moodiness and rage counter Charlie’s kindness and sincerity.

Each of these scenes–mostly exchanges between two characters–all start to take on a certain rhythm. If it all begins to feel like a play, it’s because the film is based on one. Screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter adapts his 2014 stageplay here for the film (which also lends itself to a COVID production).

For a film about a 600-pound man, I was very surprised to find how much I connected to it. Timely, issues that we experience now such as self-isolation, self-medication, grief, and shame, are all things that we can struggle with every day. In a post-COVID, mostly online world, I was taken aback to see how easy and dangerous it is to fall into our own worlds of isolation and despair that can grow from shutting oneself off from the rest of the world.

It’s a brave story to bring to the screen, and it’s Brendan Fraser who deserves every word of praise that his performance is getting. Incredibly moving, Fraser proves he’s a singular talent here, bringing a yearning presence to Charlie. Further, he brings all sides to this character suffering from grief and addiction. Communicating the pleasures of inhaling a bucket of chicken wings, meatball subs, or pizzas at any given moment, and then the physical stuntwork as well as emotional depth to convey pain inside a man who can barely move is a feat of acting and should be recognized as such.

Cinema rarely features people like this at the center of the frame, getting their own story. And Aronofsky and team, as well as the obese community, should be proud to see this character and story portrayed onscreen with such compassion and empathy, and heart.

The Whale is a transcendent film, as evidenced by its final shot. As Charlie has been saying to his daughter and students, “be honest.” By the time he reaches that pinnacle of truth himself, he is not bound by weight. He is freed by the screen ratio format and even the gravitational forces of this world. Lightness is that thing that exists within all of us if we just choose to lift that weight of despair.

1h 57m. Rated R for language, some drug use, and sexual content.

Ryan Rojas

Ryan is the editorial manager of Cinemacy, which he co-runs with his older sister, Morgan. Ryan is a member of the Hollywood Critics Association. Ryan's favorite films include 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Social Network, and The Master.