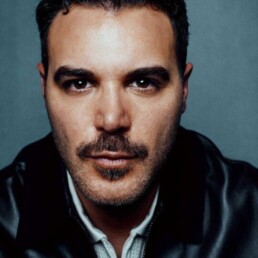

Growing up in a small town outside of Beirut, Lebanon, where he witnessed the cultural repression of women firsthand, filmmaker Zayn Alexandre has gone on to write and tell stories that celebrate humans overcoming oppression. His debut short film, the intimate sociopolitical drama Abroad, tells the story of a Lebanese immigrant couple. His second directorial effort, Manara, debuted during the 76th Venice Film Festival in the Giornate degli Autori section.

Now, Alexandre returns with his new film, Saint Rose. In our exclusive interview, the writer-director discusses how seeing the women in his life confined influenced the story, working with his mother on a personal experience, and how the film is about “the human desire for freedom and self-actualization.”

What inspired you to create Saint Rose? Could you talk about the personal experiences that led to the creation of this story?

Zayn Alexandre: Saint Rose was inspired by the women I grew up around, who navigated societal norms and expectations by succumbing to them or through quiet defiance. Seeing my mother and other women in my life unable to reach their full potential because of roles imposed on them profoundly influenced me.

Life became a state of confinement for them, with moments of joy reduced to small, fleeting pockets of freedom they had to seek. My mother and sister, in particular, inspired me with their resilience and strength in the face of rigid norms. This project is deeply personal and rooted in what I witnessed growing up.

The film deals with control, oppression, and breaking free from societal expectations. How did you approach weaving these heavy themes into a short film?

Zayn Alexandre: I focused on telling an intimate and relatable story. Every detail, from the setting to the characters, was designed to subtly reflect these struggles. I wanted the themes to emerge organically through Rose’s daily life.

Much of the story lies in what’s not being said. I hope the audience can feel Rose’s sense of confinement through these nuances. I would describe the film as both subtle and restrained.

The relationship between Rose and her housekeeper, Becky, is central to the film. How did you portray this relationship, and what did you want each character to represent?

Zayn Alexandre: Despite their different backgrounds, Rose and Becky are trapped by their circumstances. They are prisoners in their ways, shaped by societal expectations and personal struggles, and they’ve developed a mutually dependent relationship.

What might seem like a typical employer-employee dynamic reveals more profound similarities. Their shared sense of entrapment blurs the lines between wealth and privilege, creating a complex and deeply human bond between these women.

You mentioned this film was a love letter to your mother and sister. How did working on such a profoundly personal project affect you emotionally throughout the filmmaking process?

Zayn Alexandre: Tapping into deeply personal issues, which are still ongoing, was very challenging. Working with my mother on a story so closely tied to our own experiences added another difficulty—I had to constantly navigate separating my role as “director” from my role as “son.” It was emotionally taxing for everyone.

The film features crucial roles played by non-professional actors. How did you approach working with them, and what challenges or advantages did that bring to the production?

Zayn Alexandre: Working with non-professional actors is challenging but rewarding. Intuition is a pretty powerful tool. Because the story was close to home to both actors, their performances came from a place of passion. Rehearsals were minimal.

It was important to create a safe environment where they felt comfortable and were not camera-conscious. Their performances needed to feel raw and genuine.

You mentioned using symmetrical and polished cinematography at the start of the film to represent Rose’s entrapment, which becomes more chaotic. How did you collaborate with your cinematographer to achieve this visual shift, and what was your intention behind it?

Zayn Alexandre: My cinematographer, Karim Kassem, and I intentionally used symmetry and rigidity in the film’s early scenes to amplify Rose’s controlled, stifling world. As the story unfolds, we opted for handheld movements and less polished framing to reflect her emotional unraveling and eventual chaos.

The film’s tone shifts from severe to almost campy and satirical by the end. How did you balance these tones, and why did you choose to end the film in such a way?

Zayn Alexandre: Life is rarely one-note, and I wanted the film to reflect that. The tonal shift mirrors Rose’s breaking point. By leaning into the satire, I aimed to highlight the situation’s absurdity and life in general.

Rose’s relationship with alcohol, particularly her secret consumption of vodka, is a significant element in the film. What does alcohol represent in the context of her emotional journey, and how did you want audiences to interpret her use of it?

Zayn Alexandre: Alcohol is both a form of rebellion and escape. It’s Rose’s secret act of defiance in a life otherwise dictated by control and appearances. At the same time, it’s a coping mechanism, a way to numb herself to her reality.

Finally, what do you hope audiences will take away from Saint Rose? Is there a specific emotion or thought you want them to leave the theater with after watching Rose’s story unfold?

Zayn Alexandre: I hope audiences leave with empathy and reflection. Rose’s journey is deeply personal but universal. It’s about the human desire for freedom and self-actualization. I want whoever sees the film to question the societal structures that limit us and feel inspired by the resilience of the many women in their lives.