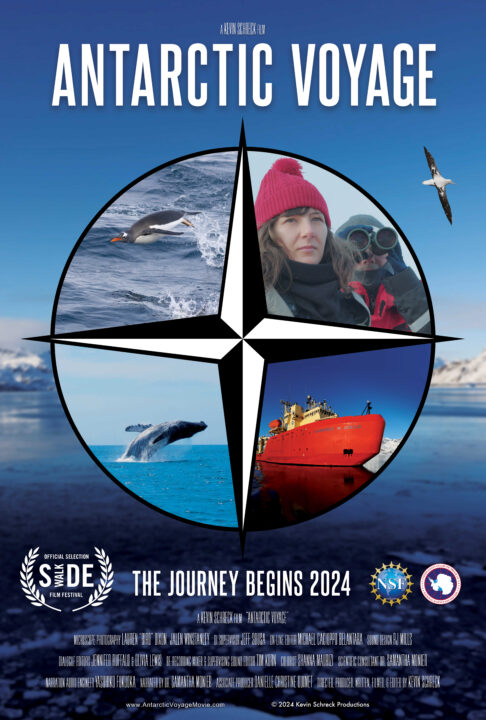

“I sincerely think that the science conducted on this voyage by these dedicated people has as much aesthetic and cultural significance as painting a mural, composing a symphony, or making a film.” These are the words from Kevin Schreck, the daring filmmaker who transformed a challenging Antarctic expedition into a cinematic marvel with his new film Antarctic Voyage. With this unique project, which shines a spotlight on the stark and breathtaking landscapes of South Georgia, Kevin shows the beauty of a world that is slowly disappearing due to climate change.

In our exclusive interview, Kevin shares how receiving a grant from the National Science Foundation gave him this incredible opportunity to make his film. Discover how he navigated the icy expanses of the Antarctic and crafted a film that not only explores environmental themes but also pays homage to the grand tradition of nature documentaries.

How did receiving funding from the National Science Foundation shape your approach to this project and its scope?

Samantha Monier and her fellow scientists were applying for a grant from the National Science Foundation. Like many applicants, they were rejected by the NSF, twice. But the NSF did say that if there was a way to get the message out to the general public about what this research was for and why it mattered, then they might be inclined to fund this expedition. It was Sam who came up with the idea of hiring a filmmaker to document the process and to release a film about their research around South Georgia. I was lucky enough to be their first choice, and I jumped at the chance for this dream opportunity.

Kevin, you mentioned that as a child, you were hugely inspired by figures like Sir David Attenborough, Jane Goodall, and Carl Sagan. What aspects of their storytelling techniques did you incorporate into your own work on this documentary?

I realized in college that the reason why I was so fascinated by science and nature was because of great science communicators and naturalists like them and others. They could help even young children understand large, abstract concepts about conservation or the cosmos or deep time. I had to make sure that this information in my movie was accessible to everyone who might be watching it, without dumbing it down and feeling like we were oversimplifying anything. Part of that was through capturing the enormous scope and vastness of that landscape, to give it that epic tone.

Another ingredient in that process was to make sure the narration screenplay that Sam would read was not too didactic or too esoteric. I wanted to make sure that even a kindergartener could understand the movie, and, even more importantly, be excited by the movie, without alienating or losing the adults. It’s not really a movie made for kids, but I think it aims to capture that inner child in all of us that wants to be awestruck by the natural world. People like Attenborough, Goodall, and Sagan were champions of that: explaining big concepts in digestible, accessible, and enthralling communication and visuals. I hope I succeeded in being part of that legacy which inspired me long ago in some small way.

Can you tell us more about Dr. Samantha Monier and what drew you to feature her in this documentary?

Sam and I were friends back in college, and became even closer after graduation. I always knew that she had an interest in the performing arts, which meant that she wasn’t camera-shy or nervous around a microphone. She’s a great science communicator, and an educator, herself. With that charisma, she was a natural fit to be a human anchor in this story. There are a lot of themes that the film explores, and no singular, Hollywood-style, three-act narrative structure. So I think Sam helps tie things together elegantly, bringing a charismatic presence that warmly invites the audience into this adventure.

Antarctic Voyage intertwines elements of a modern-day adventure film with the poetic beauty of a visual tone poem. Can you elaborate on your creative process for crafting this distinctive approach?

It was more of a byproduct of how we were filming than anything else. I don’t really study other films when I’m prepping for or in production on a movie, or even when I’m editing. It’s only toward the end of post-production that I start to notice what might have inspired me in the past and made this movie what it is. The adventure film elements definitely come from the fact that this is an exciting expedition to a part of the Earth’s surface that few have visited. But the visual tone poem qualities are more elusive, and less intentional. This movie doesn’t have a conventional, Hollywood narrative, so I wound up capturing a series of feelings and moments that, when stitched together, form a semblance of what it was like to be down on that ship.

As a result, it’s a bit more avant-garde than the usual nature documentary, hopefully for the better. But it wasn’t exactly on purpose. It just came naturally to me. I’ll look at the movie now and go, “Oh, that’s kind of going for the grandeur and intrigue that I feel from Werner Herzog’s early 16mm documentaries,” or, “That microscope footage kind of has this alien quality like Jean Painlevé’s experimental science films,” or “Wow, I guess the editing rhythm of those Soviet montage films by Dziga Vertov from the silent era that I saw in college really stuck with me.”

One person said Antarctic Voyage felt “like 2001: A Space Odyssey set in the Antarctic,” which we both understood as a compliment, as we’re both Kubrick fans. But again, I don’t think about influences until my movies are almost finished. If I did it any earlier, I would fear becoming derivative or phony. Your inspirations will show up no matter what, so you might as well just be honest with the process and not go for homage or imitation right from the start.

In what ways does Antarctic Voyage differ from traditional nature documentaries, and what do you hope audiences will take away from this unconventional perspective?

I think part of what makes this movie feel different is it isn’t especially didactic. There is a lot of educational information in it, for sure. But it doesn’t preach to you or tell you how we ought to live in order to save this marine ecosystem or our biosphere in general. It explores ways in which humans have had impacts on South Georgia’s ecology, both good and bad, but it’s not an instruction manual. I think the movie is more of a musing on just what it’s like to be down there, at sea, isolated from civilization for several weeks, and living a different life while doing amazing things with your life.

Weirdly, I felt humbled and thrilled by just how small I felt amid that expansive, indifferent landscape. It made so many of my more pedestrian, mundane concerns from daily life wash away. But it wasn’t escapism, either. Rather it was a sobering jolt of reality, of what our planet really looks like beyond our homes and screens. I hope people get that sense of awe and connection with nature through this film, even via their screens at home.

What were some of the most challenging aspects of filming in such a remote and harsh environment, and how did you overcome them?

It costs a lot of money to make these expeditions happen, but that’s mostly for renting the vessel, hiring the crew, cooks, and marine technicians, and making sure we had enough fuel, food, and other supplies to last us at least four weeks at sea, among other necessities. So, the budget for the filmmaking portion of the grant was quite small. There was not enough in the budget, or enough room on the ship, for a sound recordist, second camera operator, or production assistant.

Luckily, I was used to being a one-man-band filmmaker, and working inexpensively. I was prepared to do everything myself, which I had done before on my previous feature-length documentary, Tangent Realms: The Worlds of C.M. Kösemen (2018), and often have done on my forthcoming project, Enongo. But that was on dry land and rarely far from civilization. his was my first time making a movie at sea, and in a polar environment. So it was a real gamble. I didn’t even know if I would get seasick or not before going aboard our vessel. Luckily, I did not get sick.

Can you share a memorable moment or experience from the expedition that had a significant impact on you or the film?

The most dramatic moment of making the film happened at the very beginning: due to chaotic storms – ironically exacerbated by anthropogenic climate change – thousands of flights were canceled or delayed in North America in one day, including our flight. As a result, all of our checked luggage went missing. That included all of our clothing that we weren’t already wearing, a good amount of scientific instruments, and all of my filmmaking equipment that was too large for, or didn’t qualify as, carry-on and personal items.

My shoulder mounts, my tripod, and half of my cleaning supplies for my lenses and camera bodies were lost in transit, and could not be recovered by the airlines until after the voyage. I anticipated this might happen, which is why all of my carry-on and personal items were only the most valuable, irreplaceable gear: camera bodies, lenses, batteries, SD cards, external hard drives, and whatever cleaning supplies I could carry. So it was an already low budget production suddenly made even more low budget and rough around the edges.

But I reminded myself that other people have made films, conducted scientific research, and traveled the globe with much, much less than we had. It was just a reminder to adapt, which any independent filmmaker needs to do at any moment. I think I became a stronger filmmaker as a result of this technological setback. Even with these unexpected limitations, I still managed to make the movie exactly the way I wanted it to be made.

What role did the team of explorers play in the documentary, and how did their dedication and expertise influence the final product?

We were very lucky that everyone got along so well. There is, of course, that important balance between respecting someone’s need for privacy (especially on a relatively small ship), while also being an outlet for them to tell their story and feelings with your camera and microphone. Human beings best relate to other human beings.

I think we have a charismatic assortment of personalities in the film that were on that vessel who help ground the movie. Best of all, they – and the National Science Foundation – gave me full creative freedom, for better or for worse. That sense of trust was really vital in making this movie what it is.

How do you hope Antarctic Voyage contributes to the broader conversation about the conservation of polar regions and the importance of preserving wildlife?

I hope that Antarctic Voyage, even in some small way, shows that science and art might be different, but that they can still be mutually beneficial allies. Films and other art about science can not only communicate these broad issues of conservation, but can also highlight the aesthetic value of scientific research itself. I sincerely think that the science conducted on this voyage by these dedicated people has as much aesthetic and cultural significance as painting a mural, composing a symphony, or making a film.

Science helps us understand our relationship with the world. We human beings are not only connected to nature; we are part of nature. We never really left that animal kingdom and that vast evolutionary family tree. In a way, encountering other species is like meeting distant relatives. But while there is that kinship with the natural world, what I was filming and what the scientists were researching is also taking place in an environment that is not suited for humans. It really feels like another planet being down on the Southern Ocean at the Antarctic Convergence. You are reminded that the scope and scale of our planet is enormous, and yet everything is interconnected.

I wanted the film to capture both that sense of connection, and that grandiose sense of scale. If we can help to convey intellectual information in ways that are emotionally resonant, then it will stick with people – and then, maybe, they’ll do something about helping our planet. But they have to care first.

What advice would you offer to filmmakers, artists, and scientists based on your experiences completing this project?

My advice to all of them – filmmakers, artists, and scientists alike – is the same. In no particular order: Always be prepared to adapt; go where the evidence takes you; explain big concepts in simple, relatable terms. We are a storytelling species. Find the story in the data that you collect. Maybe it’s one, big story; maybe it’s several little stories. But stories speak to and stick with our fellow humans.