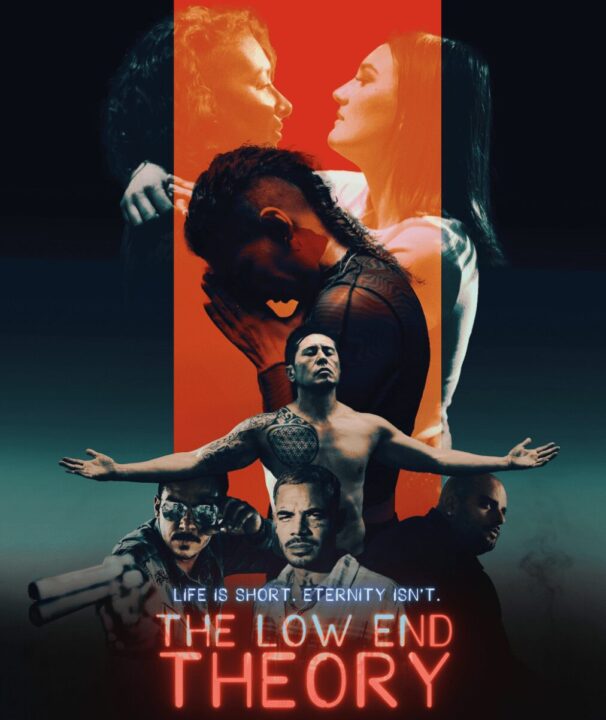

The karmic relationship we have with the universe interests filmmaker Francisco Ordonez. With his new noir film, The Low End Theory (co-written by the film’s lead, Sofia Yepes), Francisco found a way to explore this universal idea through genre filmmaking. “Mainly, I was interested in exploring the question of whether there is such a thing as a cosmic order—whether you call it God or karma. I really wanted to bring the latent mysticism or spirituality of film noir to the surface, to the text level.”

READ MORE: ‘The Low End Theory’ Review: A Neo-Noir Set in LA’s Music Scene

In our exclusive interview, Francisco discusses how his Catholic upbringing informed his making movies “about” religion, his film’s representation of LGBTQ+ and Latinx voices, and his Scorsese-an style to capture a new type of spiritual film noir.

Cinemacy: It’s a pleasure to meet you, Francisco! You’ve stated that the idea for The Low End Theory came to you when your co-writer, Sofia Yepes, brought you a personal story of hers, told as a film noir. What idea did she initially share with you, and what resonated with you enough to want to make it a feature film?

Francisco Ordonez: I’ll have to leave it to Sofia to decide how much detail she is willing to share, but I can tell you that it was the type of story that just makes you think: Wow. There are some really wild and manipulative people out there! And it’s just baffling what willing participants we can be when we’re in love or think we’re in love.

We can go as far as to put ourselves in physical danger. And we’re capable of violating what we know is right from wrong: our moral codes. And if you throw trauma in there, anything is possible. If you’ve experienced a violation but never received justice, it can really torment you. We’ve all experienced this in small ways. We’ve all experienced situations where someone insults you, and that night, you lie in bed, brooding and fantasizing about what you should have said or done.

In the case of our film, Raquel, the protagonist, has experienced a much deeper violation, one that she never addressed. This combines with this toxic relationship with our film’s femme fatale and results in some extreme noir-level decisions. Sofie mainly wanted to explore toxic love and betrayal. And that’s where I said: “Oh, that’s a noir.” Then we met in the middle, with the themes that she brought to the table on the one hand and the things that interested me on the other.

Cinemacy: What was the collaborative process between you and Sofia – who also stars – in writing the film? Can you talk about what incorporating Latinx and LGBTQ+ characters and ideas about fate and destiny into the story meant to you?

Francisco Ordonez: In terms of the writing, Sofia supplied the pieces of the story and the initial emotions, and I started writing a treatment. I would write and then send it to her. She’d give me notes, and I’d revise them. I did this for about a year. The final treatment that we wrote the script from was about 25 pages, single-spaced. I always write a treatment. I like the freewriting of it. And I like the way it allows me to see the entire film from a birdseye perspective, that is, all the acts and movements. A treatment is almost as good as an outline or post-it beat sheet in this respect.

When I’m writing in screenplay format, I find that I can only “see” the scene before the one I’m working on. And maybe I can see one or two scenes ahead. At least, that’s the way it works for me. Once we got to the script stage, I would send Sofia the script as well as our other producer, Dan Ragussis. I’d get notes and keep revising. As I kept writing, Sofia’s initial ideas morphed into more hyperbolic versions of the original circumstances. It got to the point where the story took on a life of its own and had its own requirements. Like all great actors, Sofia asks great questions about the narrative and the characters. During the writing process, she called me on nuts and bolts logic, as well as emotional logic and motivation.

Mainly, I was interested in exploring the question of whether there is such a thing as a cosmic order—whether you call it God or karma. I really wanted to bring the latent mysticism or spirituality of film noir to the surface, to the text level. People who know my work will recognize the spiritual themes (I guess you can call it “spiritual”) that I often return to. I don’t think anyone would call my films “religious films” or “religious scripts” but instead, films that are about religion.

My theory is that I’m drawn to these themes because I went to a Catholic school starting from kindergarten. I remember being marched into confession after my first communion every Wednesday. I must have been about 7 or 8 years old. At a young age, I was obliged to think about Hell, sin, and salvation. Today, I consider myself a lapsed Catholic, but those themes and questions are hardwired into my brain. I can’t shake them. They’re in there, they’re potent, and they keep coming out in my work. When Sofia and I discovered that our main character had a fixation with karma, that was an a-ha moment for me; that’s when I found my own personal way into this story.

My parents are from Ecuador. Sofia was born in Medellin and moved to New York as a baby. We’re both Latino, so in that sense, it’s only natural that we’d incorporate Latinx characters into the writing even while not necessarily making an effort to make a “Latino film.” Same with LGBTQ+. Sofia identifies as pansexual and while this film has helped her navigate through that journey, we never necessarily set out to make an LGBTQ+ or Latinx film, per se.

Our objective was to take people we are familiar with, put them into a classic genre we love, and show the industry what we, as underrepresented people, can accomplish if given the opportunity. Actors like Robert Deniro and William Hurt solidified their stardom in neo-noirs, Deniro in Taxi Driver and Hurt in Body Heat. Noir anti-heroes are wonderful and challenging roles to play, and Sofia has shown that she can deliver and hold an entire film on her shoulders.

Behind the camera, you have me, a Latino director, a female Latinx producer, and a star in Sofia. Our director of photography (Gemma Doll-Grossman), Production Designer (Marina Pérez Ramirez), and film editor (Miriam Kim) are all women. We had a real presence of women, LGBTQ+, and people of color in front and behind the camera in key positions. That was one of our big goals, and we succeeded. Hiring from underrepresented communities is activism. It sounds like a slogan, but I believe it to be true, and I will continue to live by it.

Cinemacy: What were the first steps you took to begin production after the script was complete? Who were the first key crew members that you brought on?

Francisco Ordonez: Once the script was complete, we started a crowdfunding campaign. We needed seed money to open an LLC, to hire a lawyer to create the LLC, and such. We teamed up with an associate producer, Juan Gil, and a crowdfunding consultant and raised about $25K. The 3 of us, Sofie, Juan, and myself, ran the campaign under the guidance of our consultant, Avenida Productions. (Which are great, by the way.) It was around this time, at the commencement of the fundraising phase, that our Assistant Director, Matt Marder, came on board. He started helping us think about actually making the film, scheduling it, and all of that while we were still tweaking the script.

Once we had a company/LLC formed, then we partnered with actor/executive producer, Ricky Russert and Dan Ragussis and his company Atomic Features. Both Dan and Ricky were instrumental in helping us to raise the private equity and of course, Dan produced the film through his company, Atomic. Sofia and I were blessed to work with them.

Very early on, we brought in actor Rene Rosado. Sofie, Rene, and I have been working together since I was in film school, 19 years now. Both Sofie and I knew that we wanted Rene to play the pivotal role of “Efraim,” Sofie’s best friend in the film. We knew that their real-life chemistry as long-time friends would work great in the film. I think it does.

Also, originally, Rene came in exclusively as an actor, but then he and I formed Shakti Sol Productions along with our third partner, Krishna Tewari. Shakti Sol helped produce and finance the film and consequently, our company has an ”in association” credit. Once we were officially in pre-production, we found our amazing Director of Photography, Gemma Doll-Grossman, her team and production designer, Marina Pérez Ramirez, and her awesome Art Director, Marian Wood.

Cinemacy: How did you find the right actors to embody these complicated characters, and what was your casting process like?

Francisco Ordonez: Working with the legendary casting team of Susan Shopmaker and Matthew Lessall was a blessing. They made incredible suggestions for all the roles or were pivotal in securing actors that I had targeted. For example, I had seen Sidney Flanigan in Never Rarely Sometimes Always and was blown away like everyone else. Same with Ser Anzoategui from the show “Vida.” Ser, like Sidney, was amazing to work with in terms of Ser’s commitment to the role. They’re such a nuanced and intense actor—intense in the best way.

Like Rene Rosado, there were a few actors cast among our friends. For example, Eddie Martinez plays “Uly,” Scotty Tovar plays “Nico,” and rapper and entrepreneur Berner plays “Tino.” They’re friends but they’re also amazing actors that we knew would deliver. It’s really important for me to know that everyone I’m working with is committed to the material, and it’s not just a paycheck. You need that, especially in independent films where paychecks are not necessarily exorbitant. I made sure that everyone we cast had that passion for playing the role and being part of the film.

Cinemacy: Can you describe The Low End Theory’s visual style and how it aligns with traditional noir aesthetics while incorporating your unique perspective? Were there any particular films or filmmakers that inspired you?

Francisco Ordonez: For the most part, The Low End Theory doesn’t directly align with a traditional visual noir aesthetic. That was intentional. A lot of classic noir films are rooted in German Expressionism. Given that we filmed in color, I didn’t want to try that style because I felt it would be compromised.

One of the things that I find really fun about neo-noirs, from Chinatown to neo-noirs made today, is that they don’t necessarily have a unifying visual style. They deliver echoes of classic noir via hairstyle or wardrobe (The Last Seduction is a good example of this), but overall, there’s a real eclecticism to the visual aesthetic in neo-noirs. What unifies neo-noirs is the experimentation with the narrative elements of the genre.

With this film, I was looking forward to filtering those narrative elements through my own visual instincts. While I didn’t go for German Expressionism, I was influenced by what I’ll call “Scorsese-an expressionism,” as well as the surrealism of Jacque Audiard’s Un Prophete. Scorsese comes into play via slow motion at certain moments when Raquel is faced with a big decision. We decided that we’d use slow-mo in those pivotal moments combined with tripod shots in what is otherwise a mostly shakey handheld film.

To really pull off Scorsese-an expressionism, you need a preponderance of fluid Steadicam and dolly shots, which I knew we couldn’t pull off based on our schedule. I knew we had to shoot fast, so we opted to shoot 85% of the film with a handheld camera (combined with a lot of available light) and relegate the smoothness of tripod shots to a few well-chosen moments so that those moments really mean something when the audience experiences them.

As far as Un Prophete, our film’s “ghosts” are inspired by Audiard’s film. I love the way that in Un Prophete, the apparition is really an effortless manifestation of guilt versus being explicitly supernatural, you know, a “ghost.” And yet, in Un Prophete, there is nonetheless a kernel of something supernatural about the ghost that I can’t put my finger on. The ambiguity is really nice and resonant for me in that film, so I wanted to play with that in a noir context. This was, for me at least, another way to pull the mysticism of noir up from the subtext to the text.

Cinemacy: The setting can significantly impact a film’s tone. How did you choose the locations for this story, and what atmosphere were you aiming to create?

Francisco Ordonez: Independent films have to be very practical about locations. We had to shoot in places we could secure. And yet, we were able to get some great-looking locations. And by “great,” I mean they look visually appealing but also real to the story and the characters. Our production designer, Marina Pérez Ramirez, was instrumental in this via her artistry and vision and by generously devoting untold hours to scout with me. She really helped to ensure that we secured locations that she could make look striking and narratively appropriate.

Another consideration was the fact that I love showing parts of a town that don’t get enough screen time in most movies. For me, that was places like the downtown Los Angeles alley where two characters have a conversation or the bus that Raquel rides to work. We don’t really see the inside of L.A. buses in movies. That was fun shooting in those buses, let’s say, unannounced, even though it was tricky to shoot. Shout out to Sofia and our director of photography, Gemma, who were great sports about getting on those buses and shooting stuff guerrilla.

Cinemacy: How did you secure funding for The Low End Theory, and what advice would you give to other indie filmmakers looking to finance their projects?

Francisco Ordoñez: Three things: First, Tailor your budget to the amount of financing you can raise. Whether you write it yourself or find a script, get behind one that you absolutely adore. You have to be 1000% passionate about any story if you’ll have any chance of success. But do your best to tailor your budget to the financing that you can realistically raise. It’s a tricky thing to decide in advance how much you can raise before you’ve done it. But what’s the point of trying to raise, say, $20 million for your first film when it’s practically impossible to ever get it off the ground?

Nothing, of course, is impossible, but when you’re starting out, there’s so much to learn about the business of raising money, and the more you’re trying to raise, the more you don’t know. It behooves aspiring directors to make their film, to “get on the board,” because there’s just so much to learn about the craft of directing. It’s a mistake to ignore that the outliers are directors with debut films that are masterpieces.

Many think that Scorsese’s first film is Mean Streets, while it was his third. (Or fourth, if you count The Honeymoon Killers, from which he was fired.) Many people think that Tangerine is Sean Baker’s first feature, while it was his fourth. The only way to practice your craft is to make a movie, one you believe in. Therefore, it’s absolutely critical to make one, so get behind a doable project, one that you love, and bring it to life.

Second: Don’t try to produce by yourself. Find a producer, one that is as passionate about your project and about becoming a producer as you are in becoming a director. The key is finding partners to help you raise money that are as incentivized to see the film made as you are. Our initial crowdfunding raised $27K. I couldn’t have raised that amount without Sofia and our associate producer, Juan Gil. Same with the equity we raised. My producers and exec producers, several of which were also actors, were pivotal in raising the money. I could not have done it by myself.

Third: Pick one project and throw yourself behind it like an obsessive maniac. There’s a reason why so many people want to make a film but never do. The answer is that it is so damn hard to pull off. Unless you have a trust fund, you won’t do it as an afterthought. You can’t dabble in producing an independent film. It’s just impossible. I found that I had to stop doing everything else other than “work-work,” that is, work to keep the lights on. Once I realized that I had to put down all the side pet projects, music videos, short films, and devote utter focus to The Low End Theory, that’s when things started to move, that’s when money started to move into our account.

Cinemacy: What emotions or questions do you hope audiences take away from the film, and how do you see it resonating with them?

Francisco Ordonez: Our noir hero really struggles with whether it’s right or wrong to do what she does in the name of love. She’s someone who walks around believing that “what comes around goes around,” and she interprets events through that lens. She’s in a transactional relationship with the universe—trying to do good so it comes back to her and avoiding transgression for the same reason.

I think most of us live this way to some degree, even if it’s at a subconscious level, which makes it a universal film. I hope that, however you see Raquel’s ultimate fate, it entertains you and that you think about these questions at least a little about how they relate to your own life.

Hello! I just finished going through your article, and I have to say it was truly enlightening! You’ve done a fantastic job of highlighting some key points that don’t always get the attention they deserve. I especially liked how you laid out your ideas—it felt very relatable to me. I’ve been exploring a similar topic on my own site, focusing on [mention relevant subject], and I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts on it. Thanks again for providing such valuable insights! Keep up the awesome work!