“I don’t know what to write yet. To me… the world is a mystery.”

That’s how Jong-su, the lead of the enigmatic South Korean thriller, Burning, answers when asked about his novel. He’s an under-employed creative writing graduate, a few years out of college with not much to show for it. And folks, I may not have understood every socio-political implication in this film, but at least I got this swell new catchphrase out of it. The next time someone asks me about my plans for my twenties I will definitely channel Jong-su and stare evenly at them while mumbling “I don’t know. To me… the world is a mystery.”

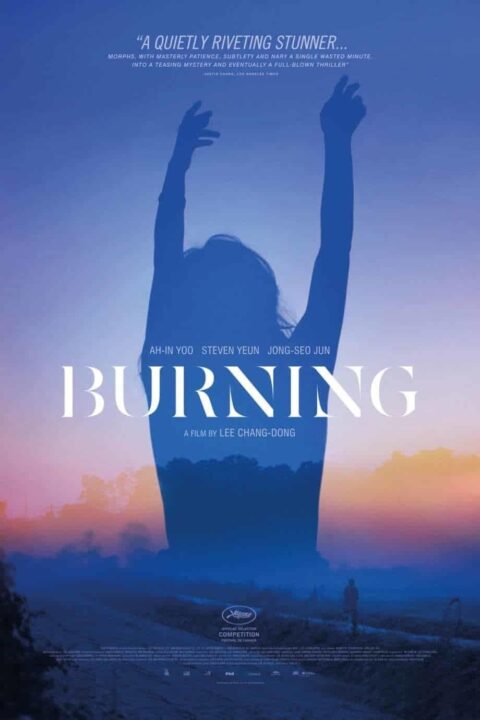

That said, don’t get the impression that this is a gently comedic coming-of-age story. I meant it when I said the socio-political underpinnings here are a tangle. The main plot involves the directionless Jong-su (played by acclaimed Korean film star, Yoo Ah-in) falling into a love triangle with a girl from his hometown and a wealthy playboy. The most pivotal scene involves this young woman dancing topless at sunset through the fields of her hometown at the border of North and South Korea, mimicking the movements of flocking birds, until she collapses while the Korean flag ripples in the background. For many viewers this visually and thematically dense sunset ritual will rank among the most richly interpretable scenes of the year. For others, it may be beautifully shot exploitation, riddled with clichés of the volatile, earthy female whose naked body represents the desire to reconnect with physical reality in a hollow modern world. There are a dozen other interpretations we could emblazon onto her skin. I’m split between the mainstream response crying masterpiece (the film is among the year’s best reviewed) and the small but reasonable backlash saying the thriller raises dazzling ideas but loses them in tropes of tragic girls and obsessed men.

I don’t particularly connect with the film’s bleak vision. And yet I don’t deny that vision’s craftsmanship. Accomplished director Lee Chang-Dong (Poetry, Secret Sunshine) knows just when to mete out information to keep an audience yearning, adding more mysteries and ominous moments to the film’s Jenga-like structure. Much unease stems from the unsatisfied, troubled characters, who all have reasons to tease, manipulate, or harm one another to fulfill their own desires.

I don’t particularly connect with the film’s bleak vision. And yet I don’t deny that vision’s craftsmanship.

The drama begins with a chance meeting. Jong-su runs into his mysterious childhood neighbor, Hae-mi (played with wide-eyed intensity by Jong-Seo Jeon), after she’s been rendered unrecognizable by plastic surgery. She’s a free-spirited presence who sweeps Jong-su into a relationship. She loves to re-invent herself, dancing and speaking with an emotional rawness that Jong-su lacks. The mounting unease that will define the film begins early, with a fumbling sex scene in which Hae-mi tells Jong-su that as kids he would cross the street just to tell her how ugly she was. Jong-su can’t remember this or any of the childhood events Hae-mi recounts.

The plot thickens when Hae-mi travels to Africa to seek a group that teaches people to release the small hunger of life to seek the “Big Hunger” of spiritual meaning. When Hae-mi returns she is not alone. Joining her is the fit and wealthy Ben, played by Steven Yeun (Walking Dead, Sorry to Bother You) in his first Korean-language role. Once this main trio is in place the film bursts with ambiguous rivalries.

Jong-su and Ben are constantly contrasted. Where Jong-so is slouching, Ben is suave. While Jong-su is burdened by his family’s financial troubles, Ben commands vast wealth. When asked, Ben won’t say where he works. Jong-su calls him a Korean Gatsby, ranting: “How does he live like this at his age? Traveling abroad, driving a Porsche, listening to music while cooking pasta.” I will always find it hilarious that when Jong-su lists the most suspicious, unreal aspects of a twenty-something man he includes cooking pasta with music. He seems to believe that Ben is everything insincere while his own connection with Hae-mi is real. Jong-su claims he’s an observer of life’s mysteries rather than a judge, but we watch as his, and our, judgmental, pattern-seeking impulses flare at Ben’s behavior. Before long, Jong-su gets the idea that Ben’s interest in Hae-mi is sinister. Ben says he has never cried and observes Hae-mi’s outbursts and Jong-su’s affections with detached amusement.

Things escalate irreversibly after Hae-mi’s sensual dance in the fields. Jong-su calls her a whore for performing in front of Ben. Hae-mi takes this insult quietly and stops reaching out to Jong-su. Then, a mysterious phone call suggests she’s been attacked. Jong-su launches his own investigation of Ben, who doesn’t show concern about Hae-mi’s absence. This search for evidence drives the last act of the film.

I won’t spoil the conclusion. I’ll only say that the more we watch these characters the less sure we become of them. Are their relationships sincere or transactional? Are their memories honest or unreliable? If creeping dread and haunting mysteries fire you up, you’ll get endless fuel from Burning, though you may never be able to make sense of the charred remains.

‘Burning’ is not rated. 148 minutes. Opening this Friday at ArcLight Hollywood and Laemmle’s Royal Theatre.

Kailee Andrews

Kailee holds a Communication Arts B.A. from the University of Wisconsin. At 21, she programmed her first film festival for an audience of 4,000+ on campus. Since then, it's been all about sharing the cool arts and crafts of cinema.