Alex Lykos Dares to Disconnect From It All

The next time you're out in public, look around. What do you see? It will likely predominantly be people on their smartphones, living in their own worlds. However, one person you won't see doing that is Alex Lykos.

With his new documentary Disconnect Me, director Alex Lykos does a 30-day digital detox in which he stops using his smartphone to become present with the world. In our exclusive interview, Alex talks about the reason for ditching his smartphone, and his outlook on phones: "Let's talk about our relationship with technology in a pragmatic, mature manner, not in a preachy manner because kids will switch off if we do."

Related: 'Disconnect Me' Attempts a 30-Day Digital Detox

What prompted you to take this 30-day smartphone detox, and when did you decide to make a documentary about it?

I started noticing how all-consuming my habits had become. I was looking at my phone over dinner instead of talking to my wife. I wasn’t in the present with my family, enjoying family time. Instead, I was mind-numbingly scrolling through my socials. But I was feeling worse after doing it, causing you to drop into the rabbit hole of comparing your life to those you see on social media. And I was like, "Hold on a second, where is the return on investment here? I’m spending an hour doing something and feeling worse after doing it."

I decided it was time for a circuit breaker, and to hold myself to account, I had a camera follow me. And it just grew from there into this film which expanded into covering a lot more than just my journey.

What were the first steps you took to begin this documentary?

I wrote a list of some of the things I would like to do during the experiment, one of which was to spend more time outdoors. I did lots more exercise and took up golf again, which I hadn’t played in a while.

One of the most unique elements of the film is audience participation, such as when you ask people to raise their hands if they use their phones in the restroom, as well as asking them to vote with their smartphones using a QR code on the screen. How did you decide to include these moments?

You know how at the beginning of the movie, we get that announcement asking us to turn our phones off? No one ever does. So we thought, "You know what, with this film being about that device in their pockets, let's get them to use it."

And if I may add, from the screenings we have had so far, this is a film best watched in the cinema with an audience, because it is a communal experience. There is a very unique energy in the cinema with the film being about a device that everyone is holding. Some are using it throughout the film, some aren’t. There is a very unique energy in the room.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zXvV5vcxMWQ&ab_channel=LykosEntertainment

A particularly moving moment comes after you reveal to people how their smartphones are made by child laborers, to which they reply it's simply a “necessary evil." How did you feel hearing these responses?

I think the answers highlight just how dependent we are on smartphones, and how hard it would be for anyone who is addicted to their phone to part with it.

What unexpected challenges did you face while making the film?

The challenges of trying to communicate with the crew, dealing with logistics issues, communicating with family, and coordinating daily routines were the biggest.

What were your favorite moments in the film?

After listening to the student Angelina talk about her struggles with social media, we hear this extraordinary voice. It moves me every time I watch and is a stark reminder of the potential negative impacts of social media. At our Australian premiere, she came out after the film.

What do you hope the film achieves?

If the film can instigate a discussion between parents and their children, or between partners or friends, then that is all we are hoping to achieve. Let's talk about our relationship with technology in a pragmatic, mature manner, not in a preachy manner because kids will switch off if we do.

Alex Lykos, where are you from?

Sydney, Australia.

Can you talk about what drew you to pursue theater and the arts?

I used to play tennis, and when I stopped playing, I felt lost. Writing allowed me to express what I was feeling, and it just grew from there. The first story I wrote was about the reunion of two best friends: one a professional tennis player, one a professional drug dealer.

How did you get your start in filmmaking?

I started in the theatre in 2006 and made several shows until about 2013 when I adapted Alex & Eve, our most popular stageplay, for the screen. Alex & Eve's film was completed in 2015.

What have you learned about working in indie film? What did you wish you knew before you began?

It is a grind, a real grind. If you don’t love telling stories, it can be very disheartening. You have to love it to make an independent film. That and sound is the most important element of any film.

Any next projects we should know about?

I am working on a feature film titled The Lady Echindas, another documentary, and a television series titled Jawbone.

What messages and themes are important to you that you wish to explore in your future work?

Generally, I like to explore themes relating to the challenges we all face in trying to navigate life, trying to explore the purpose of it all.

Louise Woehrle Shines a Light On Our Integral True Stories

The adage goes that the first step to solving any problem is recognizing there is one. This can be quite challenging to do, as acknowledging problems oftentimes comes with needing to face our fears, insecurities, and shame head-on. That is why we need brave filmmakers like Louise Woehrle, whose new documentary A Binding Truth shines a light on a vital story of two friends who learned of their shared family ancestry through their ancestor's slaveholding roots.

Related: 'A Binding Truth' Uncovers a Complicated Familial History

In our exclusive interview, Louise Woehrle discusses how by confronting our nation's dark past of racism and slavery, we can all heal and grow stronger together. She also discusses the behind-the-scenes work of bringing the story to the screen, her production company Whirlygig Productions, and her message for her future film work: "I believe we need more stories that help us see each other with more compassion, understanding, and acceptance."

https://vimeo.com/842917169

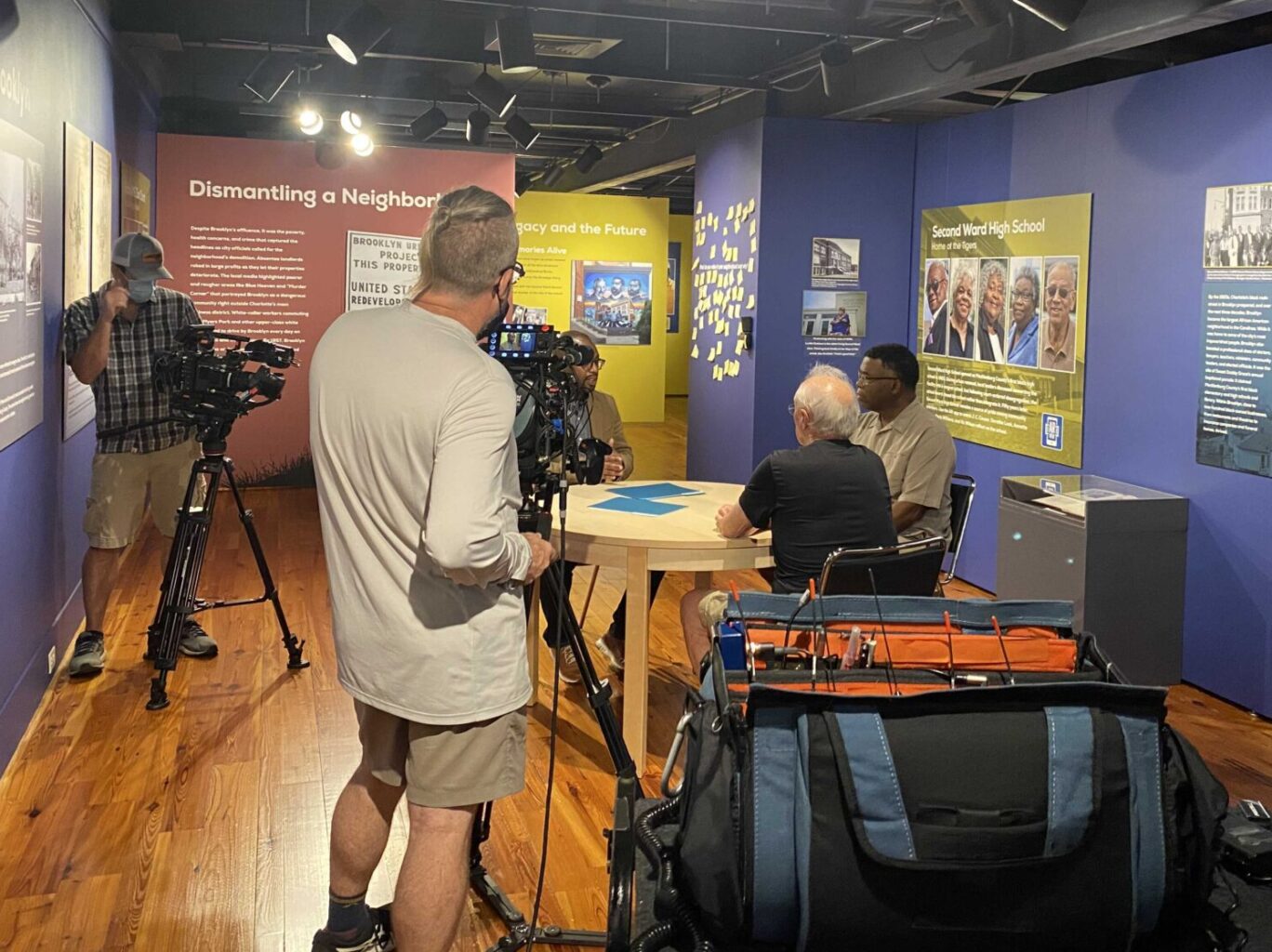

C: How did you first learn about the incredible life story of Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick, the main subject in your documentary, A Binding Truth?

Louise: I first learned about Jimmie and his story when I was in New York screening my previous documentary Stalag Luft III - One Man’s Story. My cousins Ellen and Katie Holliday attended the screening. Katie is married to De Kirkpatrick, the other central subject in our film.

C: In 1965, Jimmie integrated from his all-Black high school into an affluent white high school in Charlotte. One of his classmates, De Kirkpatrick, shared the same last name. Almost fifty years later, a shocking discovery was made that De's ancestors were slaveholders who owned Jimmie's ancestors. What was it like for you to learn of that moment, and how did you want to handle that in the film?

Louise: It took my breath away because I knew what a shock this was to De. I wanted to tell this part of the story with the truth and in an authentic way. De was more than willing to stay open and honest in pursuing the truth of his slaveholding roots. There were no rose-colored glasses.

C: What were the first steps you took to begin this project?

Louise: My executive producer, Jay Strommen, and I flew to Charlotte to meet with Jimmie and De. We talked in depth. We listened to them and shared our interest in doing a documentary about their story and why it was so important. They agreed it was a good idea and a good fit - we were off and running!

After that, I knew I needed fundraising tools, starting with a sizzle reel. Thankfully, Jay provided our start-up capital. Next, I went to FilmNorth, located in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul to get our fiscal sponsorship set up through them. They are a 501c3 that has served as a fiscal sponsor on several of my films, thereby allowing contributors to donate to our project as a charitable contribution.

I next contacted Gary Schwab, a journalist for the Charlotte Observer who had written a 3-part series with David Scott about Jimmie in 2013 and subsequently a story in 2014 about Jimmie and De reconnecting decades after high school. Gary was a wealth of knowledge. Next, cinematographer Chip Johnson, a longtime friend and colleague, and I filmed interviews with Jimmie Lee and De and shot some broll of them in the Sardis Slave Cemetery.

I gathered photos from both men, and Chip worked with me to edit a 13-minute sizzle reel. Next, a friend of De’s, Jock Tonissen, organized a fundraiser luncheon held at Myers Park Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, where I met our lead fundraiser Chuck Hood. Chuck got out there and raised most of the funds with Lauren Batten of Vandever Batten.

C: There are several deeply emotional, delicate moments shared between Jimmie and De that you portray sensitively in the documentary. What were those moments like for you to edit?

Louise: Jimmie is a very sensitive person who can share his emotions. Delving into his past was very emotional for him. He says in the film, “When you do this kind of work, your emotional tank needs to be full.” De is sensitive, too, but is more analytical. I mean, he is a forensic psychologist, so that makes sense.

When we were editing the film, it was my goal to show both men in their true light. Thank you for saying that those moments were handled with sensitivity.

C: You contextualize their story by also showing parts of our nation's larger, problematic history with racism and slavery, using incredible archival footage. In particular, I was so moved to hear the voice recording of the former enslaved Fountain Hughes. How did you go about finding all of this footage?

Louise: The research never stopped from pre-production through post-production. It takes a lot of time and due diligence. We found incredible images and footage. When I heard the Fountain Hughes recording from the 1930s, I knew he was our link to help connect the past to the present. What he says is so powerful as a former enslaved person.

Most of the images were found through various archives in Charlotte libraries and museums, while others were found in the National archives. I had dedicated researchers on the project, so it wasn’t only me digging for gold.

C; What challenges did you face while making the film? What were your favorite moments in the film?

Louise: I would say telling the story of Jimmie and De when they first met nine years ago was challenging, but I think we figured it out. One of the biggest challenges was letting go of some great stories that did not make it into the film. My goal was to keep the length at 90 minutes. It was so tough.

One of my favorite moments in the film is when we are surprised by Emma, age 92, with her uncanny ability to read people, her humor, and her honesty in talking about her own family’s history as slaveholders. Another moment is when Jimmie takes us back to his past with his son JJ, and De’s time in the cemetery with Jimmie, with a voiceover of De reading prose he wrote titled White Bones.

C: While your documentary uncovers a lot about the past, the film also looks towards the future, with the message about how we must acknowledge our atrocities and have difficult conversations with each other to learn and grow. What do you hope people take away from the film?

Louise: I hope that people will see themselves somewhere in the film and relate to the stories - be touched in some way. I believe that when we are awakened by the truth, it allows us to see things through a new lens. The truth is what I hope is conveyed through Jimmie and De’s stories. How people react to the film will be theirs to share, hopefully in positive ways.

We have already witnessed that the film sets the table for personal conversations about race and the Truth of America’s Slave history and how that ties to racism today. I know that Jimmie and De show us a way forward.

C: Louise Woehrle, where are you from?

Louise: I grew up and live in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

C: How did you get your start in filmmaking?

Louise: I was previously an actress in theater and on-camera, doing commercials and voiceover work. My first job as a producer was at a small production company. The owner had seen a Birthday video I was working on for my dad and his twin brother. I was still married at the time. The co-owner of the production company asked how long I had been a producer, and I told her that I wasn’t a producer. She said, “Yes, you are,” and told me that if I ever wanted a job, she would hire me.

So, when I got divorced, my two boys were 5 and 8 years old, and I needed a job - I took that lovely woman up on her offer. That’s where I learned to be a filmmaker and all the various aspects that are involved. It was like getting paid while going to school.

C: Can you tell us more about Whirlygig Productions, the production company you founded in 2002?

Louise: After working at that small production company for 3.5 years, it was time for me to fly on my own. So in 2002, I committed to telling stories that mattered. I started my company Whirlygig Productions as an independent filmmaker. There was no studio, only me.

I created a mission statement for Whirlygig: “Telling stories that help us see ourselves and others in new ways, promote healing, and connect us as human beings.” I have stuck with that mission and love that I get to serve as a conduit for stories that matter. For me, that means shedding light on important stories that need to be told that can serve as catalysts for change.

C: What have you learned about working in indie film, and what did you wish you knew before you began?

Louise: I have learned so much about myself and what matters to me by telling stories about so many different people, places, cultures, and causes. I realize the power of storytelling and how much we can learn from each other. I also feel it's a privilege to shine a light on stories that can positively affect lives and how important trust and integrity are in being able to do that.

C: Who are your filmmaking heroes and dream collaborators?

Louise: I have many film heroes, but in the documentary world, I would say Ken Burns and Waad Al-Kateab.

C: What messages are important to you that you wish to explore in your future work?

Louise: I’ve always been interested in mental health and being there for young people. We need to shed more light on trans young people and their stories. There are far too many deaths by suicide, and I believe we need more stories that help us see each other with more compassion, understanding, and acceptance.

Elan Golod Preserves History Through Our Elders' Unheard Stories

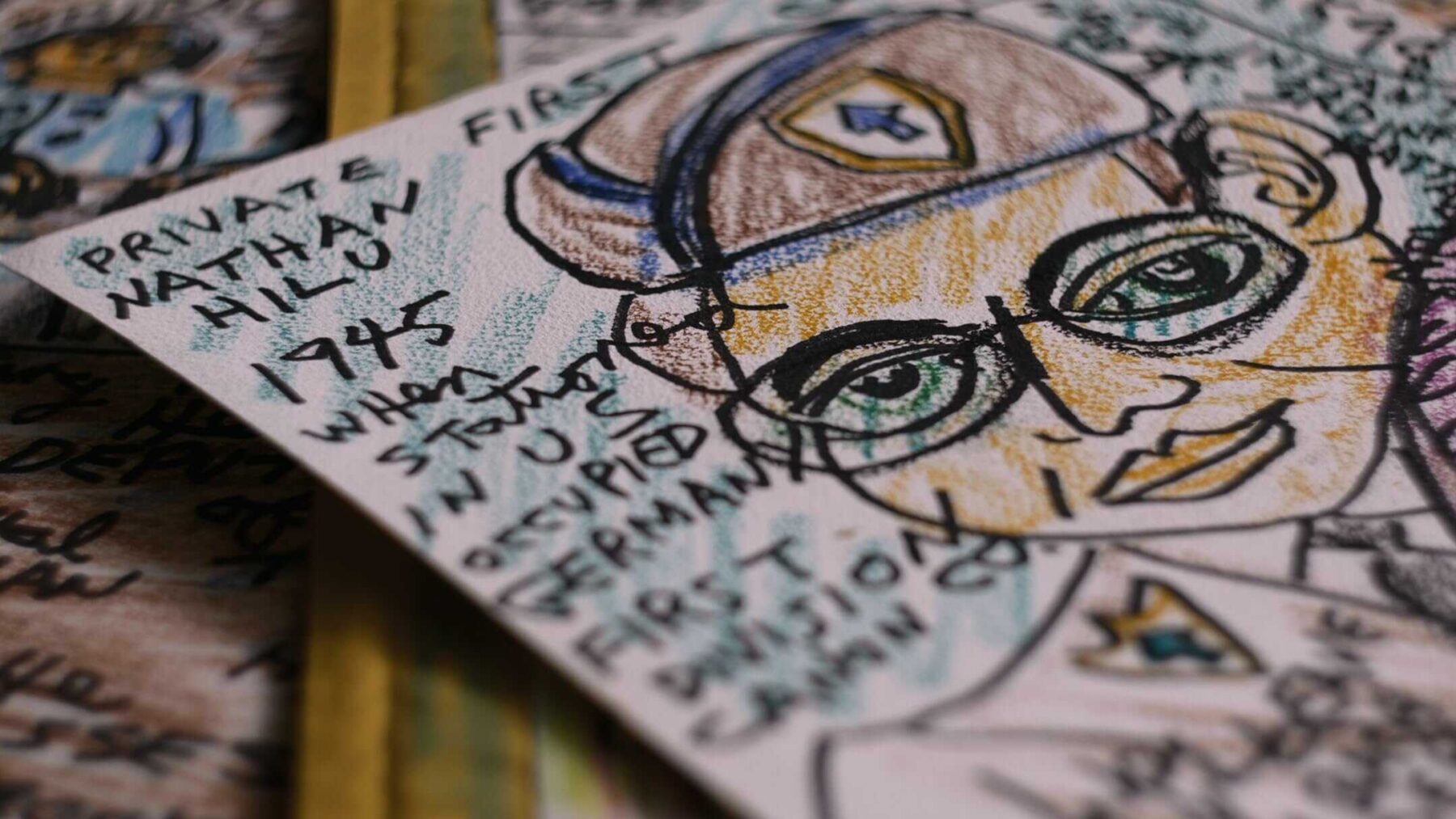

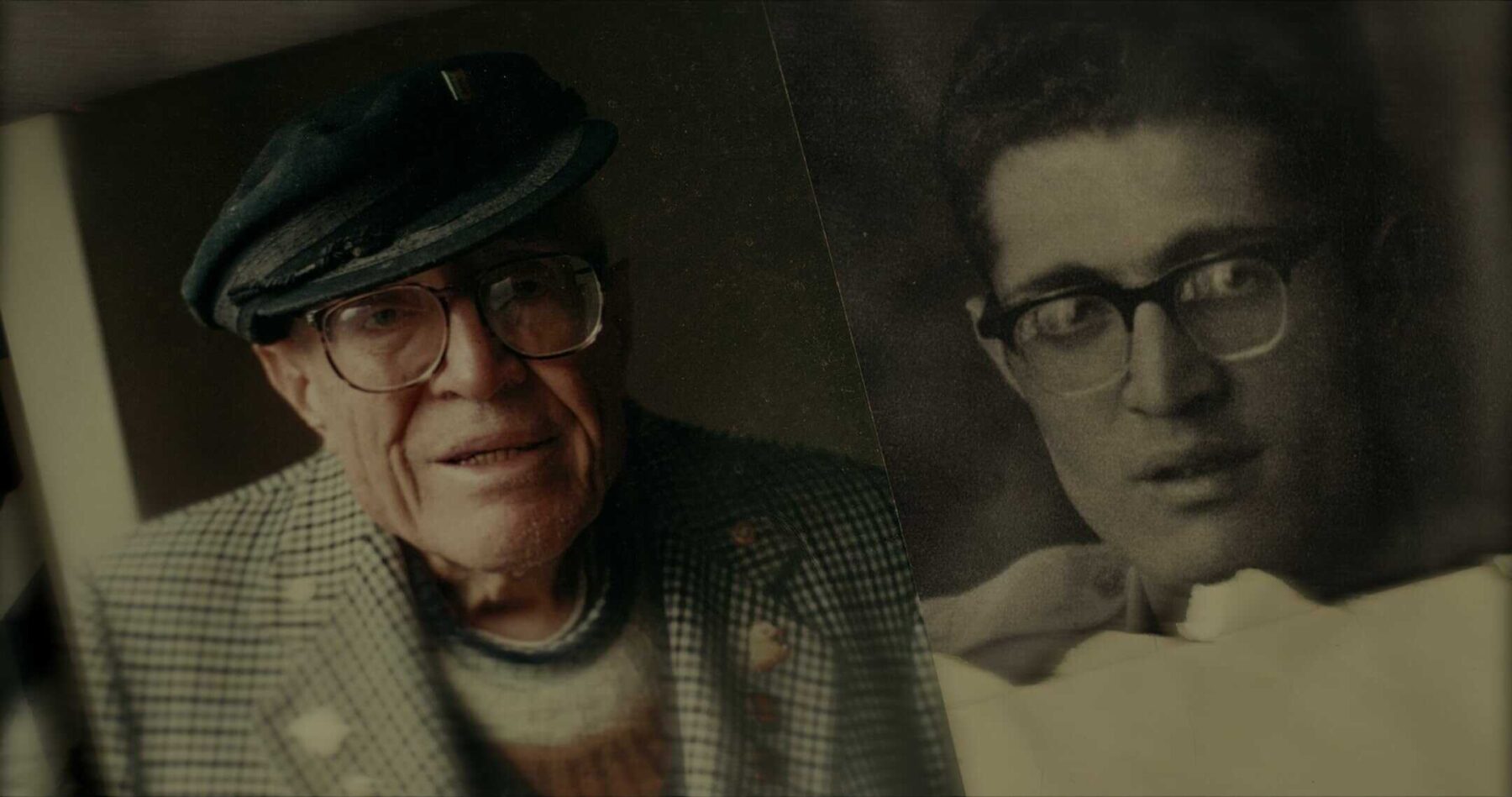

With his large eyeglasses, thick suspenders, and slumped posture, Nathan Hilu may appear at first glance to be just an elderly man on a couch. But by looking closer, intentionally listening, and putting a camera in front of him, we learn that he's a man not only rich in stories but with an abundance of artwork that illustrates pivotal moments in world history. And bringing this man's life and stories to the screen is Elan Golod, director of the new documentary, Nathan-ism.

Nathan-ism tells the life story of Nathan Hilu, a Jewish veteran who guarded the worst criminals responsible for the Holocaust following WWII. But as the documentary reveals more about the expressive Nathan through seeing him sketch his quickly drawn cartoons–capturing monumental life moments relying on memory alone–we also learn that there may be some questions as to the authenticity of the stories as Nathan remembers them.

Related: 'Nathan-ism' Explores Truth and Narrative Through This Cartoonist

In our exclusive interview, Elan Golod shares the process and challenges of making Nathan-ism, the film's upcoming screening at the Nuremberg Memorial ("It’s incredibly gratifying that Nathan will have his story shared in the very room where many details about the Holocaust were brought to light"), and the biggest takeaway after making the film and working in independent filmmaking.

How did you first learn about Nathan Hilu, the subject of your documentary and directorial debut, Nathan-ism?

I was going down the internet rabbit hole searching for potential documentary-worthy stories and I came across an article in a small Jewish magazine about Nathan Hilu and an exhibition he had had at the Hebrew Union College Museum. I was immediately struck by the dramatic circumstances of his Nuremberg experiences.

I was also intrigued by the cognitive dissonance of this heavy subject matter treated in these vibrant Crayola colors, unlike much of the existing canon of Holocaust-related art. That felt inherently cinematic and worthy of deeper exploration of the person behind these visual memoirs.

At the beginning of your film, Nathan shares that there are many art “isms”: Futurism, Impressionism, and now, “Nathan-ism.” How would you describe the “Nathan-ism” art style to audiences?

If "Nathan-ism" were featured in art history books it would probably be defined something like this: Rooted in the expressive storytelling of individuals like Nathan Hilu, this distinctive approach involves the skillful translation of personal narrative into a vibrant visual language, creating a unique fusion of storytelling and artistic expression that immerses viewers in the intimate and vivid landscapes of individual memories.

At first glance, Nathan’s art might appear amateurish and childlike to viewers, made with markers and crayons. But they are deceptively deep once you see that the cartoons are his life’s memories, specifically of being a Jewish prison officer guarding the highest-profile criminals of the Holocaust during the Nuremberg trials. What do you find striking about the juxtaposition between his playful cartoons and their grave historical subject matter?

To me, Nathan’s drawings offered a unique opportunity to convey a narrative linked to the Holocaust from a fresh perspective, diverging from the conventional portrayal often seen in previous Holocaust films. So much of the visual documentation of the Holocaust is in black and white which leaves the viewer somewhat removed. In stark contrast, Nathan’s artwork feels like it is bouncing off the page and screaming at you with the same urgency as Nathan’s storytelling style.

What were the first steps you took to begin this project?

After reading about Nathan Hilu online, I reached out to Laura Kruger, the curator of the Hebrew Union College Museum. She provided me with Nathan’s contact info but warned me that he was “quite the character” and that he wasn’t the easiest to deal with.

I cold-called Nathan and explained my interest in documenting his story. Initially, it took some time to gain Nathan’s trust and get him on board with the project. I visited him over several months without any camera or recording equipment, just sitting and listening to his stories over coffee. Nathan was very excited to have a willing audience for his stories and eventually felt comfortable enough to start sharing his stories on film.

What was the process like to bring Nathan's artwork to life using animation?

From the outset, I felt that harnessing Nathan's vibrant artwork with the right animation treatment could authentically immerse viewers in his deeply subjective perspective. During the conceptualization phase, I stumbled upon the work of Héloïse Dorsan Rachet, a Paris-based animator who had done beautiful animation sequences for Michelle Steinberg's documentary "A Place to Breathe." Rachet's animation style, with its childlike and innocent quality, left me convinced she could effectively replicate Nathan Hilu's unique artistic flair.

To ensure the animations stayed true to Nathan’s original work, we embarked on an extensive series of animation tests, prioritizing authenticity above all. Nathan's abundant drawings, featuring key figures from the trial and pivotal scenes within the narrative, served as an invaluable visual foundation guiding our meticulous animation process.

https://vimeo.com/815880849

What challenges did you face while making the film?

My relationship with Nathan was not the traditional filmmaker-subject relationship. While Nathan's personality added a captivating layer to the narrative, it also posed occasional challenges during the filmmaking process. Each time we filmed with Nathan, it was like a “show-and-tell” session in which Nathan shared the stories behind his last batch of drawings. Nathan was very much intent on crafting his narrative, leaving little room for interjecting questions. Here and there, by curating the drawings I had him talk about, I was able to steer the conversation towards the topics I wanted to cover.

For the research about Nathan’s military service, I was unsure what our digging would unearth. At times it was a struggle to wait patiently while our archival research attempted to shed more light on Nathan’s time in Nuremberg. But as viewers will see in the film, the patience paid off.

As you just touched upon, the film takes an unexpected turn when it’s brought into question whether or not Nathan actually lived each of these experiences as he says he witnessed. This being a documentary, and you being so close with Nathan as a person, what was it like for you to include this part in the film?

This is an aspect I discussed extensively with my therapist. Navigating the intricate relationship between my roles as both a filmmaker and Nathan's friend demanded a delicate balance. I intended to thoroughly delve into Nathan's life story and delve into the depths of his psyche while avoiding the risk of putting his memory on trial in the process.

This required a nuanced approach, where our friendship served as a foundation for trust, allowing the exploration of his narrative with sensitivity and respect. I’m thankful to say that despite some tense moments featured in the film, I managed to maintain my friendship with Nathan until the very end.

Nathan-ism will have a special screening at the Nuremberg Memorial on February 13th. What does having this screening at such a sacred site mean for you?

I am truly humbled by this honor and I’m beyond excited that Nathan’s legacy and this film will have such a full-circle moment. It’s incredibly gratifying that Nathan will have his story shared in the very room where many details about the Holocaust were brought to light. In 1945, the four allied powers behind the Nuremberg trials had hoped that the trials would deter future aggression by establishing a precedent of holding war criminals accountable in international court. So it is very unusual and timely to showcase this film as conflicts persist in the Middle East and Ukraine

What would you say is the biggest thing you learned from Nathan, and what do you hope people take away from the film?

The most actionable lesson I learned from my time with Nathan is taking the time to listen. There are so many elders like Nathan, who have an abundance of remarkable stories waiting to be unraveled. Taking the time to truly listen not only honors their wealth of wisdom but also forges meaningful connections that transcend generational boundaries. In a world bustling with noise, dedicating moments to absorb and cherish the narratives of our elders becomes a powerful act, unlocking a treasure trove of experiences that might otherwise be lost to time.

Let’s get to know you better! Elan, where are you from, and how did you get your start in filmmaking?

Raised in Israel to an American mother and Israeli father, my journey unfolded with an unexpected twist as I found myself creating training videos as part of my mandatory service in the Israeli army. Post-army, I pursued a deeper understanding of filmmaking at New York University and went on to work as a film editor on both scripted and documentary films. This collaborative learning experience has significantly shaped my directorial approach.

What have you learned about working in indie film, and what did you wish you knew before you began?

Unfortunately, I've become increasingly aware of the challenges facing the documentary filmmaking landscape, with market trends narrowing the range of documentaries able to secure distribution. Nevertheless, I maintain a hopeful outlook for the emergence of fresh opportunities for daring documentary content, and I am determined to actively contribute to this essential transformation.

What messages and themes are important to you that you wish to explore in your future work?

I am currently deeply intrigued by the concept of legacy and the imprint we leave on the world long after we're gone. At the moment I’m starting to explore a story related to this idea from within my own extended family.

For updates and more information on 'Nathan-ism,' head to the film's website.

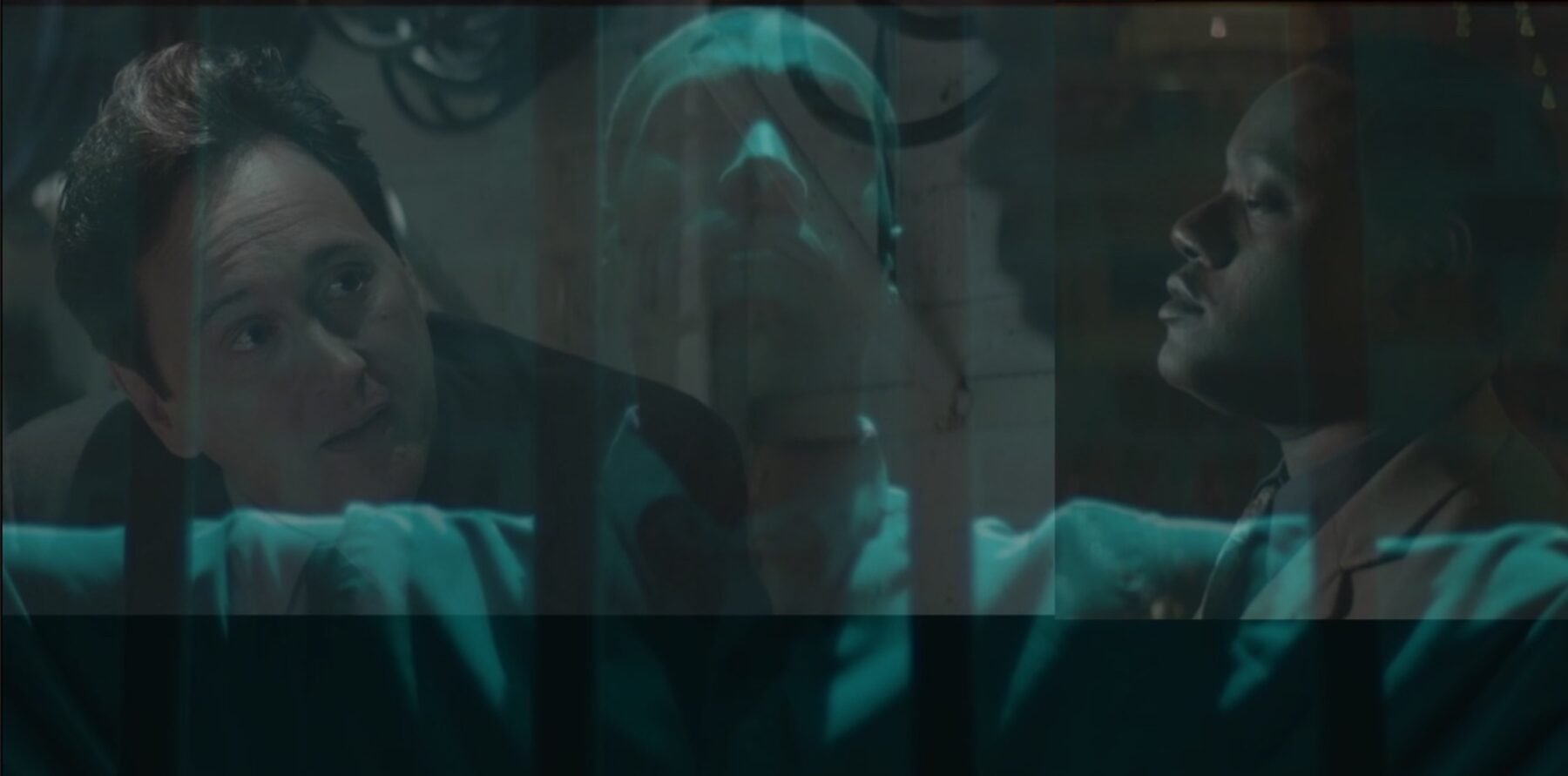

Sundance: 'A Real Pain': A Heartfelt Trip Through the Hurt We Feel

Among the films I saw at this year's Sundance Film Festival was the second feature film written and directed by Jesse Eisenberg. Humorous, heartfelt, emotionally honest and altogether moving, it was the best film I saw at the fest. It's called A Real Pain, which stars Eisenberg and newly-awarded Emmy winner Kieran Culkin as a pair of cousins who, following the death of their grandmother, travel to Poland to join a Holocaust tour. Seeing the historical sites of their family's history, they are given the chance to reconnect to their ancestry as well as with each other after time spent apart.

With eyeglasses and a general nervousness, David (Jesse Eisenberg) is introverted, anxious, and altogether cut off from his emotions. He's less than comfortable leaving his wife, child, and job behind to vacation with his free-spirited cousin Benji (Kieran Culkin), whose pajama pants and tousled hair reveal the responsibility-free life he lives.

After reconnecting at the airport, the cousins touch down at their first hotel in Poland (where Benji has already pre-shipped his large package of pot, which he consumes in small doses along the way. They join the rest of their travel group, along with their guide (excellently played by Will Sharp). Although the trip and stops along the way are all pre-planned, what is not as predictable are Benji's emotions, which David is surprised to see fluctuate wildly, from delightful to distraught.

Benji is reeling hard from his grandmother's passing, she being the "only one who understood him," as he shares with David. The group's daily activities visiting memorial sites and gravestones begin to bother Benji, ultimately pushing him past the brink where David and Benji are forced to acknowledge a troubling truth that lies between them, as well as confront the emotional distress they feel within themselves.

In part, A Real Pain is just a wonderfully made tour movie and will delight anyone looking to take a lovely-looking trip through the beautiful historic Polish city and countryside. The film is warmly shot, and montages set to Chopin's classical piano music (a smart inclusion, he being a Polish composer) create a calm, intimate peacefulness over this sacred ground.

On a deeper level, the film is an emotive exploration into the personal pain we all may experience, and the different ways we choose to feel, or not feel it. Eisenberg's directorial debut, 2022's When You Finish Saving the World, was a smart, sharply observed suburban comedy about a disconnected mother and son. But where that film was less inclined to dig deep into emotionally painful terrain, here, Eisenberg (a neurotic overthinker) bravely confronts emotions head-on. By portraying David (essentially an Eisenberg stand-in) as someone repressing emotion through medication and denial, along with Benji as the uninhibited but volatile opposite, we see the film's biggest statement: that choosing to address and express one's internal pain is necessary, however uncomfortable it may be.

Bringing these themes to life is the singular Kieran Culkin; the "mercurial sprite" who gives the film its magical ingredient. Culkin's charisma is so singular and spontaneous, making for scenes that are as hilarious as they are heartfelt. A scene in which the group tour stops for a photo in front of a set of WWII statues becomes an exercise in improvisational acting, in which Benji directs them to pose as each of the different military members, bringing an unexpectedly life-affirming moment to the group. Similarly, the fearlessly frenetic Kieran Culkin breathes life into a story that is made even better with his presence.

A Real Pain proves that Jesse Eisenberg should continue to not only make films but confront emotions head-on. Searchlight acquired it for $10 million (one of the higher buys from the fest), so audiences will be able to see this emotionally stirring life-affirming film, giving us the opportunity to process our own pain as well.

1h 30m.

Sundance: 'Little Death' Is a Pill-Popping, Manic Mash Up

I could not have prepared myself for the twist that comes midway through one of the most bizarrely made films I've ever seen at this year's Sundance Film Festival. The movie is called Little Death, and it follows a depressed, middle-aged screenwriter (played by David Schwimmer) living in LA whose midlife/artistic/existential crisis makes for a manic, disjointed experience.

We see that he's a screenwriter who is grappling with "selling out," having made his success from a brainless TV sitcom back in the day (the parallel to Schwimmer's actual life feels pointed). He's now going through the agony of trying to get his very personal and very non-commercial project made with that earlier work hanging over his head. The stress of countless dead ends and empty promises within a smarmy, soulless industry weighs heavily on his fragile mental state.

We hear his aggravated rants against the entertainment industry, and today's modern living on the whole, in a series of darkly comical voiceovers (making me think of Tyler Durden's rants in Fight Club). These delusional voiceovers narrate over wild–and I mean wild–computer-generated AI art, which illustrates his depraved fantasies and declining mental state. We also realize that all of this could be the effects of the medication he's relying on to battle his depression and live his life.

Without giving anything away, it's around this point that a mid-movie climax ensues, and we're suddenly following the late-night journey of two pill-addicted kids played by Dominic Fike (Euphoria) and Talia Rider (Never Rarely Sometimes Always, and this year's The Sweet East). This whole other storyline takes us on a dangerously crazy nighttime adventure that they try to survive, stemming from the unsuccessful scoring of pills (which made me think of what a very different version of Superbad could have been like).

Related: 'The Sweet East': Welcome to the United States of Anarchy

Now, I was highly anticipating watching this film (being a fan of David Schwimmer) and had fairly high hopes for this movie. But I'll be honest, I was already not loving the first half of the film. And when it took its abrupt turn into an even less interesting, more painful second act, I was quite ready to leave the film behind.

Little Death is the directorial debut of Jack Begert, a music video director who has worked with Kendrick Lamar, Olivia Rodrigo, and James Blake, to name a few. Begert attempts the very ambitious idea of making and connecting two quite different types of stories to try to make something that comes together full circle in a larger way. But it's an attempt that doesn't work at a basic enjoyment level.

Now, I will say that Begert's creative swing is a big one. Experimenting and challenging the form is integral to cinema so that storytelling can evolve (and it's great that Sundance continues to foster this type of artistry). At the very least, Begert is making a statement about some pretty important topics in today's culture: depression, addiction, and overly-prescribed medication which are necessary conversations to have.

Little Death was in part produced by Darren Aronofsky, who similarly explored drug addiction with the painfully visceral Requirem for a Dream. But Little Death is a tonal mess and really could have benefited from Aronofsky giving Begert some notes in the editing room. While the film awaits distribution, it would benefit by having some much-needed cuts lest it suffer a quiet death of its own when it releases.

1h 50m. 'Little Death' is currently awaiting distribution.

David Zum Brunnen and J. Mardrice Henderson Resurrect Icons

Most people may know about the prolific writer Richard Wright and his classic novel Native Son, a seminal work in American history. Lesser known, however, is that he also developed the story into a stage play, working with groundbreaking author Paul Green to do so. The process would not be an easy one, as the creative collaborators were forced to acknowledge and discuss the racism that very much divided the segregated South at the time. The story behind bringing this joint effort to the stage is dramatized in the new feature film The Problem of the Hero.

Portraying the two American icons are David Zum Brunnen and J. Mardrice Henderson, playing Green and Wright respectively. In our exclusive interview, David and J. Mardrice discuss their processes of bringing such historic characters to life and the complicated state of debate and dialogue today, as well as their experiences and challenges in indie filmmaking, of which their passions run deeply.

The Problem of the Hero dramatizes the story of groundbreaking author Richard Wright and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paul Green as they work together to adapt Wright’s acclaimed novel Native Son into a Broadway play. What were each of your processes like for researching and ultimately creating these historical figures that you portray in the film?

David Zum Brunnen: Most everyone in North Carolina of a certain generation (mine or older) grew up aware of who Paul Green was (is), as he was quite intentional in the use of his craft, his art, toward his social justice activism. I was raised in a household where reading and a love of history were prevalent. As I grew up, and in my undergraduate studies, I couldn’t avoid reading Paul Green, and my fascination with his work and his life–the living of his life and his activism (in NC and the southeast US)–has never relented.

I’ve seen and heard recorded interviews with him. I’ve read his plays, his works, and works about him. In some ways, I feel as if I’ve lived closely with him for the last twelve years since this project was initially conceived. He considered himself a "folk philosopher." That stirred my curiosity even deeper.

J. Mardrice Henderson: Coincidentally enough, I was not at all familiar with Richard Wright before becoming a part of this creative process. I’ve been an admirer of the Harlem Renaissance era with an affinity for writers such as Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and Zora Neale Hurston. I even auditioned for Native (the play written by Ian Finely that precursors The Problem of the Hero) with a Langston Hughes poem. After reading that script, I knew I had to learn more about Mr. Wright both personally and creatively.

I started with Native Son, which is as brutal as described both onstage and on film, especially for his time. I read books about Mr. Wright from some of his contemporaries. I also found some visual footage to try and infuse his mannerisms and characteristics into my performance. Mr. Wright was certainly an intellectual and a pioneer of his time and his craft.

Audiences have not largely seen characterizations of each of these historical figures before onscreen. What did you find was important to materialize in your characters?

DZB: I hoped to be as authentic as possible with the gift of the script provided by James A. Hodge & Ian Finley. Yes, I need to know who Paul Green was in the living of his life, what his behaviors were, his phrasing, and his "voice," but it was also important for me not to merely imitate him. Authenticity is key. We’ve been asked if these two men spoke as they do in this film, and I can confirm that they did indeed speak & write in the fashion we attempt to convey.

JMH: There is always some trepidation when portraying individuals who existed, especially when said person is beloved by many. There’s a pressure of getting it right, doing it well, and not tarnishing this person’s legacy. That is why research is important as well as finding where the art and the artist merge.

I was able to find similar characteristics and personality traits that Mr. Wright and I share. Both he and I have a thirst for knowledge and aren’t afraid to go against the grain regarding our passions. This, I believe, lends itself to the honesty and gravitas of a performance.

https://vimeo.com/786684025

The story, written by James A. Hodge and Ian Finley (adapted from the stage play Native by Ian Finley), largely rests on your characters shared dialogue, which explores topics about race, social justice, politics, and personal & creative agency quite deeply. What was it like for each of you to read the script on your own as well as together for the first time?

DZB: Well, I was engrossed by Ian’s stage script and James & Ian’s screenplay from the first read. But allow me to tell the story of when we held auditions for the stage play, Native, by Ian…

Serena Ebhardt (the director of the stage play) and I agreed that I would portray Paul. We had already workshopped the play at Deep Dish Theatre in Chapel Hill, NC, and were now looking to tour it. In walked Josh, and we both knew we had our Richard Wright. It was immediate as we sat there in the studio theatre. And then we just sat there, still, and listened to Josh perform a Langston Hughes poem.

JMH: Upon receiving Ian’s script, after being cast, I was simultaneously anxious and excited. It’s a two-character piece with heavy dialogue, both in weight and length. And though I am removed from a lot of what Mr. Wright endured in his upbringing, there was something ancestral about his story and his experiences.

My father had told me of some of his experiences growing up in the 1960s that mirrored Mr. Wright’s experiences long before him. What I truly loved about Ian’s script is that it relays Mr. Wright’s experience without the “angry black man” trope, but a man who has been formed by his circumstances that subsequently impassioned his creative momentum. Once rehearsals started with David and Serena, all the pieces came together so beautifully. It was an instant family.

How did you both work on your scenes? Were there any significant moments of discovery during this making, either in pre-production, rehearsal, or while shooting?

DZB: We’d already performed the stage play while touring some East Coast U.S. venues. But the screenplay is vastly different in some respects: the rhythms, the phrasing, the setting. While we had the screenplay in hand before rehearsals and before principal photography began, the script was changing daily. So, we had new lines each morning; sometimes even as we were filming the scene. The moments of discovery never ceased actually. Everything was new, each time. The screenplay was like putting on a different set of clothes from the stage play.

JMH: I had become comfortable with Ian’s script after having toured it many times. However, the screenplay was different in a lot of ways. It took some time to get used to the new dialogue and beats. There were often rewrites at the start of each day of filming which kept me on my toes. Many times David and I would go off in our separate corners to grasp the new rhythms and then come back together to combine our separate work; almost like a boxing match, but without the blood.

The film was directed by Shaun Dozier. What were the larger themes and ideas that he wanted to ensure came through in the film, through your performances? Was there any particularly insightful guidance or direction you remember him giving to you that you still remember?

DZB: Credit it to Shaun (and our cinematographer, Steve Milligan, and producer, Ayana Johnson) for establishing a strong sense of ensemble and adventure on the set each day. That element was essential for both cast & crew and I believe it shows in this film–where the whole ends up greater than the sum of its parts.

Shaun’s influence is all over this film–particularly in his guiding us through the emotional journey of each character. He was mindful (when we couldn’t be) of the emotional build for each scene and what intention we brought to each moment–particularly as we were shooting completely out of linear sequence, of course. I’ll admit that for me, there were a few moments of struggle with his very fine strokes of the director’s paintbrush and his specific adjustments for each take, but they were worth it.

JMH: I applaud Shaun for his creative vision and for knowing exactly what he wanted to do with this piece. There were times when I wasn’t quite certain how the puzzle was going to come together, but Shaun made us all comfortable and guided us well. Each time I see the film, I am in awe of the transitions and cinematic choices Shaun made.

I also have to give accolades to our DP, Steve Milligan, and our producer, Ayanna Johnson for both their professionalism and candor. It was certainly a safe, wonderful, inspiring atmosphere which–with this being my first feature film–I will cherish forever.

At its center, this story is about a difference of opinion between two people. It turns into a contentious dialogue but makes the audience think deeply about each of their perspectives and histories. How do you feel the story speaks to today’s culture or disagreement and how we relate to others of different ideologies?

DZB: I find this to be a quintessentially American story. Particularly with the tenor of the times in which we find ourselves. We live in a precarious time with a great many questions of how we live and work together unresolved. We are struggling to come to terms with someone else’s perspective that challenges us to think differently, and that perhaps hints to us that there’s more for us to learn from one another. We are struggling with embracing empathy.

That said, this is a brief moment in time in the extraordinarily full and creative lives of two brilliant men from the 20th century. And as difficult as it is to see how this story unfolds, it all happens in a fashion without the need to inflict violence on one another, and without an artificially imposed limit to the number of words or characters with which one can communicate. Yeah, I’m pointing to social media when I say that, and would it be so that we could all take the time to listen and perceive as fully as these two men tried to do in their own lives.

JMH: One of the things I love most about this story is that, at its center, it’s a story of friendship. These are two individuals who both admired and cared about each other. Their penchant for storytelling on culture, socioeconomic structures, and injustices is what made them contemporaries. With that as the foundation, the conversation that these two men have is much more palatable than having two men of different races arguing over such issues.

These issues are just as prevalent today as they were in that hotel room in the 1940s, however, many come to the table only wanting to be heard and not listen. We live in a nation where the lines of separation are so evidently clear. There’s no cause for compassion, no enamor for empathy. We move about the world in silos where our interests are mainly self-gratifying and egocentric. I truly feel that The Problem of the Hero presents a version of ourselves that is willing to listen, to understand, to amicably agree to disagree, and to be okay with that.

What are you most proud of about this film and what do you hope audiences take away from it?

DZB: The audience response has been most telling. The post-screening discussions that have occurred at every film festival thus far. They mirror each other. And as we’ve said at each screening, we’re still processing this film and its impact ourselves. And they’re the same conversations that occurred pre-production, on set every day amongst cast & crew during filming, during post, and on and on…

Ian and James’ writing has struck a chord for folks–particularly in light of the feedback we’re getting. Their response has mirrored our answers above–that this is a story that speaks deeply to the times in which we live–locally, nationally, and globally. With this film, we’ve asked people to embrace discomfort. It’s clear that for many this film and that discomfort still lingers with them.

JMH: I am proud that I can present one of the founding fathers of Black literature to his adoring fans and hopefully create new ones as well. I have been incredibly blessed to be on this journey with the group of individuals telling this story. I hope that the audience listens to what is being said between these two literary giants. I hope they digest not just the arguments but the experiences that support the arguments.

There have been many times where audiences have agreed with one author and disagreed with the other at the start. However, as the film progresses, their allegiances sway in a different direction. This is a film that has to be seen more than twice to really grasp all that it encompasses and ultimately leads the audience to question their own bias and prejudices.

Let’s learn more about you both: where are you both from and how did you get into acting?

DZB: I’m from a small town in North Carolina, called Salisbury. An idyllic place to grow up, because my parents made it so for my sister and me. But a place where life’s lessons are also plentiful. I’m a bit slow sometimes so I’m still learning some of those lessons. My kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Nell Troxler, cast me as a shepherd in the annual Christmas play. I sang a song, and then was instructed to rest on the stage floor "in the stable near the manger." I took the note. I fell asleep, and I’ve been at home on the stage (or the set) ever since.

JMH: I, too, come from a small town–Ridgeway, North Carolina. It’s one of those places where you drive through, look back, and ask “Did you feel that?”. However, I never let my rural upbringing deter me from my BIG dreams. I fell in love with acting and writing early on. I remember playing a frog in a Disney-inspired production in the 1st grade. From there I began creating characters and stories on my grandmother’s front steps.

I followed that passion to the University of North Carolina at Greensboro where I received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Acting. From there, I began doing community theatre, student films, short films, and web series. I’ve been featured in the International Black Film Festival for the past two cycles. I’ve also had some of my original work featured on online platforms as well as onstage workshops.

Who are your acting heroes, and what are your favorite performances of all time?

DZB: Besides J. Mardrice Henderson you mean? (big smile)

I always have a difficult time with this kind of question, because I feel pressured to remember all the wonderful performances I’ve ever experienced, in film & theatre. And there are a LOT. I also tend to lean to mention those I’m working with at a given moment, as I always find myself learning from those I’m playing opposite.

There are numerous actors here in North Carolina and the Triangle region here in NC from whom I’m always learning. One of ‘em is in the film: Derrick Ivey. Derrick can do anything; any role. I’ve said it often; he’s a remarkably gifted artist in many respects, not only as an actor but as a director, designer (a farmer, too!), you name it.

JMH: Oh, there are an abundant amount of actors/performances I admire. Denzel Washington in Glory, Morgan Freeman in Lean on Me, Viola Davis in Doubt, and Whoopi Goldberg in The Color Purple, just to name a few.

Gosh, from this list, seems I need to watch some more comedies. I also really enjoy working opposite great actors who are in the moment with me and can elevate a scene beyond what’s in the script. I truly enjoy working with David in every iteration of this script. Our bond has both big/little brother elements as well as mentor/mentee. I believe that is why so many of our performances have been met with such great accolades. Our personal and professional relationship aids my performance with aplomb.

We would love to hear more about your experience working in indie filmmaking. What has been your experience working outside of the studio system, both positive and negative? Do you have any wisdom or lessons learned along the way that you can share with up-and-coming artists?

DZB: As an ensemble, the core creative team had the opportunity to make the film that we wanted to make. At the same time, I can’t count the number of times we’ve been dismissed; the shrugs, the "so what’s?" that we experienced in getting this film completed. I think that’s a pretty universal experience for many filmmakers. And it’s happened with practically every project our company has ever taken on in its twenty-five-plus years now.

The audiences that have seen the film thus far and the critical response hint to us that our diligence paid off. In other words. I say to our fellow storytellers… stick to it, keep at it. And know that your work is important; it’s essential. Never forget that.

JMH: This is my first foray into filmmaking of this caliber. I have been a part of filmmaking on a smaller scale, mostly as a talent. Even at this level, I have learned that tenacity is a tool to keep in your metaphorical bag. There are thousands, if not millions, with similar dreams who are more than willing to take your place. However, they can’t bring what you bring to the table. There’s an innate ability in each of us to be authentic in our quest. And that authenticity can’t be forced, only celebrated.

There are two adages I hold dear: “What’s yours is yours” and “Be yourself, everybody else is already taken."

What is it about acting that keeps you going?

DZB: Curiosity. Fear. Opportunities to learn and put myself in the shoes of others. Fear is something I’ve come to embrace over time in my life. It’s a great motivator for me, and there’s always fear that comes for me while leaping into a place where I’m reminded of how little I know.

I was raised in an environment where vulnerability is strength - and I still find that to be true. That’s what acting often is for me. I think any creative action is that for me…. embracing the fear and the fun of the unknown, and letting it be your friend.

JMH: Acting is cathartic. It has truly been my therapy in some instances. I am very much an introvert and a staunch protector of my feelings and emotions in real life. However, when onstage or on screen, I can throw aside those idiosyncrasies and allow myself the joy of being open, being honest, and being vulnerable.

I am also a self-proclaimed “forever student” and acting is the forever study of the human condition. It has allowed me to learn more about myself as I learn more about others. If fame comes, that’s a bonus, but it’s the development of the craft that brings me the most joy.

Follow David Zum Brunnen through his production company on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, Vimeo, and their site.

Follow J. Mardrice Henderson on his Linktree, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and his site.

Follow 'The Problem of the Hero' on their site.

Writer-director John Carney's crowd-pleasing movie musicals are similar to the infectiously catchy pop songs that soundtrack them so spectacularly. His movies, like the songs he helps write for them, celebrate the human spirit in heartfelt, emotional, and uplifting ways. However, underneath their charm and feel-good surfaces also lies a deceptive, painful truth that Carney can't help but fixate on: humans long to connect, despite not knowing how to communicate with each other. As his latest film Flora and Son (now streaming on Apple TV+) shows, sometimes the universal language of music is the only thing that can allow us to connect.

Set in Carney's native home country of Dublin, Ireland, the film follows fiery, foul-mouthed Flora (Eve Hewson), a lively young mother struggling to make ends meet. Spirited but scattered, Flora's world has been reduced to fit inside a cramped apartment where she is raising her young, rebellious son Max (Orén Kinlon), and where the walls rattle from the daily shouting matches before Max storms off. Warned that his punkish behavior could land him in the court system, Flora happens upon a secondhand guitar, which she tunes and gifts to her son–to no effect.

As boredom sets in, Flora decides to learn guitar herself, signing up for online lessons where she meets upbeat, Los Angeles-based Jeff (Joseph Gordon Levitt). Drawn to her hilarious sense of humor and wry coaxing, the pair become closer, and soon Jeff is sharing original songs with Flora, which inspires her to do the same. Her newfound musical interest not only gives her an identity and sense of life purpose, but becomes a way for her to connect with Max who she learns has been producing hip-hop and electronic pop music. The more music Flora brings into her world, the deeper she connects to Max and Jeff. Life, however, can get in the way of even the best melodies, she soon discovers.

Fans of Carney's (like me) will recognize that while his films are unabashedly feel-good fun, his characters are charmingly defiant rebels whose artistic spirits bump them up against the system. Going back to his directorial debut and star-making arrival with 2007's Once, to 2013's Begin Again, and through 2016's Sing Street, Carney's characters are often scraping to get by, and nearly down for the count after suffering life's punches. That is, until they discover the literal music inside of them which allows them to express their inner truths and live their fullest lives.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=beNTTHnMIy8&ab_channel=AppleTV

Flora and Son is so delightful, funny, heartwarming, and charming. And yet, while I loved it so much, it's also not Carney's best film (that remains Once, with Sing Street quickly behind). For one thing, the film is quite contained. The choice to have Flora and Jeff's relationship defined over the computer brings about limitations (I'm sure it was a conscious decision to illustrate their distance, another pandemic-era effect). However, Carney still breathes creative life into these scenes by cleverly staging ways to bring the presence of Flora and Jeff into each other's intimate living space through their conversations, illustrating the intensity of their bond

But to review the film alone would be half-complete. Scored by John Carney and Gary Clark, the original songs are once again catchy, and moving. They have played in my head since I watched it, giving me chills as I bopped around in my seat during several of the catchy numbers. The songwriting might not reach the soaring highs of Once, or the unique synth energy of Sing Street, but songs like "Meet in the Middle" and "High Life" are fantastic and deserve to stand alone outside of the film.

Beyond John Carney's writing and direction, plus the wonderful songs, Flora and Son works because of its cast. Led by Eve Hewson, who embodies the main character of Flora amazingly, balancing her foul-mouthed toughness with a tender, funny, heartfelt spirit that also announces a star-making turn (she does have star-making charisma in her, being the daughter of Bono). Pairing well with her character is Orén Kinlon as her frustrated son Max. Jack Reynor pops up as Flora's former partner, Max's dad, in a shared custody situation. And rounding out the talent, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, as Jeff, brings his naturally warm-hearted self, along with musical chops, to pair well with Flora and give the movie its heart.

Flora and Son is a funny, heartfelt film, full of humor, heart, and infectious and emotional music. If this is your first start with John Carney, I'd recommend starting from the beginning and watching all his films. Through this cinematic journey, you might even discover the music that's inside of you.

1h 37m. Rated R for language throughout, sexual references, and brief drug use.

'American Star' Is a Sluggish Final Job For This Hitman

American Star centers around the suspenseful idea, "What if an assassin's final job didn't go according to plan?"

It's the same premise that David Fincher explored in last year's film The Killer. However, in that film's plot, an unsuccessful target hit forces Fincher's contract killer to run for his life, whereas, in American Star, the target simply never shows up. Instead of endangering this film's hitman, he is left to simply bask in the ambiance of the luxurious island he's on and do a whole lot of nothing. While this sets itself up for a compelling and meditative neo-noir, there isn't enough substance or compelling story under its moody surface to make American Star intriguing enough to invest in.

Read More: 'The Killer' Doesn't Aim Too High, But Hits Its Darkly Comical Mark

Ian McShane plays Wilson, a mysteriously silent assassin whose weathered face and steely reserve allude to having lived a long, hard life. His excellently tailored black suit is as out-of-place as he is on the beautiful island of Fuerteventura where he's landed. After a long trip, he heads directly to a home where he slips in unnoticed, expecting to see the face of someone he's only viewed from a photo inside a manila envelope: that of his target, who is luckily not there, as this is Wilson's "final job" and all. Unexpectedly, a younger woman suddenly slips into the house and takes a dip in the pool. After clocking her and assessing the situation, Wilson slips away back to his resort.

Now faced with the question of whether to leave or take in the pleasures of this idyllic island. Wilson decides to stay but without an agenda. He wanders around the island, taking in the hotel's buffet, the beautiful white-sanded beaches, and the local bar. And, wouldn't you know it, Wison even recognizes the bartender as the pool-dipping woman from the target's residence–Gloria (Nora Arnezeder), and they soon strike up a conversation and exchange contacts. Not too shortly after, Wilson's associate (Adam Nagaitis) arrives at the island as his backup and keeps him company until the target arrives.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hb47dUzNUm4&ab_channel=IFCFilms

What does a lonely hitman with no other plans do while he waits, you might ask? In screenwriter Nacho Faerna's story, not very much. It's an alluring template for a story, putting a person with a complicated past in a new, unfamiliar location where they're forced to consider their life's decisions leading up to this moment. This premise reminds me of the masterful Sundown, in which Tim Roth goes on a vacation that he consciously decides to never return from. But where the revelations in Sundown made for a thrilling film, not much excitement happens in American Star. Director Gonzalo López-Gallego leans into the quiet, meditative neo-noir feel–complete with leveraging all of the noir-like tropes and characters–but throughout the film, I was largely waiting for something to happen.'

Read More: In Twist-Filled Drama 'Sundown,' Tim Roth Reveals His Shadow Self

A lot is demanded of someone to hold down a film while remaining largely this quiet, not to mention suggesting a person's backstory in their silence. In American Star, Ian McShane does so excellently, his face alone suggesting a complicated past and long life story. It's great to see him lead the film. However, without much story in the script, he can only hold the center for so long before his presence is just wasted. As the young woman he encounters, Nora Arnezeder is an alluring femme fatale type, however the suggested chemistry between them feels forced. When Gloria introduces Wilson to her mother (Fanny Ardant), it seems like they should have been a couple. There's a little boy Max (Oscar Coleman) who hangs around the hotel and nags at Wilson. The character was written to show he's a hitman with a heart, but the obviousness comes across as sappy.

The film culminates in a climactic, fate-filled end (which I won't spoil), but by then I wasn't very invested. The only interesting thing about the film is the offshore ghost ship that Gloria takes Wilson to, named the "American Star" (of which the film is named). It's a big hulking warship that's been sitting off the coast in the Atlantic for years. Wilson realizes that the ship is not much older than he is–just as it happens to sink into the ocean. While this seems to be a metaphor for his own life, it's the only moment that truly feels unexpected, and poetic. It's just too bad the film didn't explore this further.

1h 47m. Rated R for language and some bloody violence.