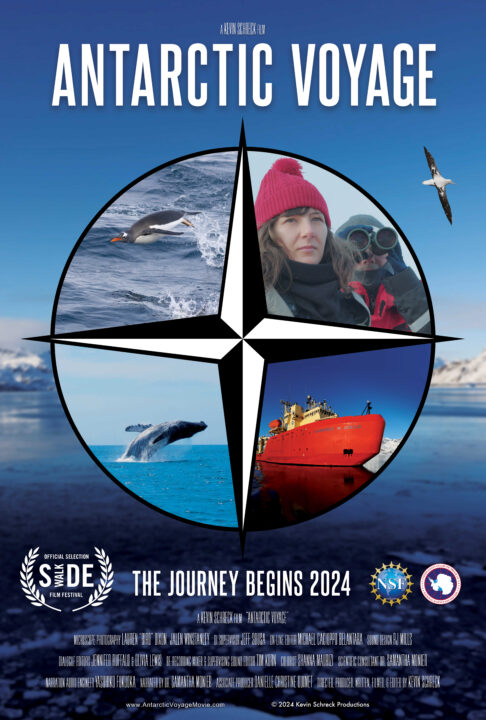

Kevin Schreck Charts New Waters And Life Adventures

"I sincerely think that the science conducted on this voyage by these dedicated people has as much aesthetic and cultural significance as painting a mural, composing a symphony, or making a film." These are the words from Kevin Schreck, the daring filmmaker who transformed a challenging Antarctic expedition into a cinematic marvel with his new film Antarctic Voyage. With this unique project, which shines a spotlight on the stark and breathtaking landscapes of South Georgia, Kevin shows the beauty of a world that is slowly disappearing due to climate change.

In our exclusive interview, Kevin shares how receiving a grant from the National Science Foundation gave him this incredible opportunity to make his film. Discover how he navigated the icy expanses of the Antarctic and crafted a film that not only explores environmental themes but also pays homage to the grand tradition of nature documentaries.

How did receiving funding from the National Science Foundation shape your approach to this project and its scope?

Samantha Monier and her fellow scientists were applying for a grant from the National Science Foundation. Like many applicants, they were rejected by the NSF, twice. But the NSF did say that if there was a way to get the message out to the general public about what this research was for and why it mattered, then they might be inclined to fund this expedition. It was Sam who came up with the idea of hiring a filmmaker to document the process and to release a film about their research around South Georgia. I was lucky enough to be their first choice, and I jumped at the chance for this dream opportunity.

Kevin, you mentioned that as a child, you were hugely inspired by figures like Sir David Attenborough, Jane Goodall, and Carl Sagan. What aspects of their storytelling techniques did you incorporate into your own work on this documentary?

I realized in college that the reason why I was so fascinated by science and nature was because of great science communicators and naturalists like them and others. They could help even young children understand large, abstract concepts about conservation or the cosmos or deep time. I had to make sure that this information in my movie was accessible to everyone who might be watching it, without dumbing it down and feeling like we were oversimplifying anything. Part of that was through capturing the enormous scope and vastness of that landscape, to give it that epic tone.

Another ingredient in that process was to make sure the narration screenplay that Sam would read was not too didactic or too esoteric. I wanted to make sure that even a kindergartener could understand the movie, and, even more importantly, be excited by the movie, without alienating or losing the adults. It’s not really a movie made for kids, but I think it aims to capture that inner child in all of us that wants to be awestruck by the natural world. People like Attenborough, Goodall, and Sagan were champions of that: explaining big concepts in digestible, accessible, and enthralling communication and visuals. I hope I succeeded in being part of that legacy which inspired me long ago in some small way.

Can you tell us more about Dr. Samantha Monier and what drew you to feature her in this documentary?

Sam and I were friends back in college, and became even closer after graduation. I always knew that she had an interest in the performing arts, which meant that she wasn’t camera-shy or nervous around a microphone. She’s a great science communicator, and an educator, herself. With that charisma, she was a natural fit to be a human anchor in this story. There are a lot of themes that the film explores, and no singular, Hollywood-style, three-act narrative structure. So I think Sam helps tie things together elegantly, bringing a charismatic presence that warmly invites the audience into this adventure.

Antarctic Voyage intertwines elements of a modern-day adventure film with the poetic beauty of a visual tone poem. Can you elaborate on your creative process for crafting this distinctive approach?

It was more of a byproduct of how we were filming than anything else. I don’t really study other films when I’m prepping for or in production on a movie, or even when I’m editing. It’s only toward the end of post-production that I start to notice what might have inspired me in the past and made this movie what it is. The adventure film elements definitely come from the fact that this is an exciting expedition to a part of the Earth’s surface that few have visited. But the visual tone poem qualities are more elusive, and less intentional. This movie doesn’t have a conventional, Hollywood narrative, so I wound up capturing a series of feelings and moments that, when stitched together, form a semblance of what it was like to be down on that ship.

As a result, it’s a bit more avant-garde than the usual nature documentary, hopefully for the better. But it wasn’t exactly on purpose. It just came naturally to me. I’ll look at the movie now and go, “Oh, that’s kind of going for the grandeur and intrigue that I feel from Werner Herzog’s early 16mm documentaries,” or, “That microscope footage kind of has this alien quality like Jean Painlevé’s experimental science films,” or “Wow, I guess the editing rhythm of those Soviet montage films by Dziga Vertov from the silent era that I saw in college really stuck with me.”

One person said Antarctic Voyage felt “like 2001: A Space Odyssey set in the Antarctic,” which we both understood as a compliment, as we’re both Kubrick fans. But again, I don’t think about influences until my movies are almost finished. If I did it any earlier, I would fear becoming derivative or phony. Your inspirations will show up no matter what, so you might as well just be honest with the process and not go for homage or imitation right from the start.

In what ways does Antarctic Voyage differ from traditional nature documentaries, and what do you hope audiences will take away from this unconventional perspective?

I think part of what makes this movie feel different is it isn’t especially didactic. There is a lot of educational information in it, for sure. But it doesn’t preach to you or tell you how we ought to live in order to save this marine ecosystem or our biosphere in general. It explores ways in which humans have had impacts on South Georgia’s ecology, both good and bad, but it’s not an instruction manual. I think the movie is more of a musing on just what it’s like to be down there, at sea, isolated from civilization for several weeks, and living a different life while doing amazing things with your life.

Weirdly, I felt humbled and thrilled by just how small I felt amid that expansive, indifferent landscape. It made so many of my more pedestrian, mundane concerns from daily life wash away. But it wasn’t escapism, either. Rather it was a sobering jolt of reality, of what our planet really looks like beyond our homes and screens. I hope people get that sense of awe and connection with nature through this film, even via their screens at home.

What were some of the most challenging aspects of filming in such a remote and harsh environment, and how did you overcome them?

It costs a lot of money to make these expeditions happen, but that’s mostly for renting the vessel, hiring the crew, cooks, and marine technicians, and making sure we had enough fuel, food, and other supplies to last us at least four weeks at sea, among other necessities. So, the budget for the filmmaking portion of the grant was quite small. There was not enough in the budget, or enough room on the ship, for a sound recordist, second camera operator, or production assistant.

Luckily, I was used to being a one-man-band filmmaker, and working inexpensively. I was prepared to do everything myself, which I had done before on my previous feature-length documentary, Tangent Realms: The Worlds of C.M. Kösemen (2018), and often have done on my forthcoming project, Enongo. But that was on dry land and rarely far from civilization. his was my first time making a movie at sea, and in a polar environment. So it was a real gamble. I didn’t even know if I would get seasick or not before going aboard our vessel. Luckily, I did not get sick.

Can you share a memorable moment or experience from the expedition that had a significant impact on you or the film?

The most dramatic moment of making the film happened at the very beginning: due to chaotic storms – ironically exacerbated by anthropogenic climate change – thousands of flights were canceled or delayed in North America in one day, including our flight. As a result, all of our checked luggage went missing. That included all of our clothing that we weren’t already wearing, a good amount of scientific instruments, and all of my filmmaking equipment that was too large for, or didn’t qualify as, carry-on and personal items.

My shoulder mounts, my tripod, and half of my cleaning supplies for my lenses and camera bodies were lost in transit, and could not be recovered by the airlines until after the voyage. I anticipated this might happen, which is why all of my carry-on and personal items were only the most valuable, irreplaceable gear: camera bodies, lenses, batteries, SD cards, external hard drives, and whatever cleaning supplies I could carry. So it was an already low budget production suddenly made even more low budget and rough around the edges.

But I reminded myself that other people have made films, conducted scientific research, and traveled the globe with much, much less than we had. It was just a reminder to adapt, which any independent filmmaker needs to do at any moment. I think I became a stronger filmmaker as a result of this technological setback. Even with these unexpected limitations, I still managed to make the movie exactly the way I wanted it to be made.

What role did the team of explorers play in the documentary, and how did their dedication and expertise influence the final product?

We were very lucky that everyone got along so well. There is, of course, that important balance between respecting someone’s need for privacy (especially on a relatively small ship), while also being an outlet for them to tell their story and feelings with your camera and microphone. Human beings best relate to other human beings.

I think we have a charismatic assortment of personalities in the film that were on that vessel who help ground the movie. Best of all, they – and the National Science Foundation – gave me full creative freedom, for better or for worse. That sense of trust was really vital in making this movie what it is.

How do you hope Antarctic Voyage contributes to the broader conversation about the conservation of polar regions and the importance of preserving wildlife?

I hope that Antarctic Voyage, even in some small way, shows that science and art might be different, but that they can still be mutually beneficial allies. Films and other art about science can not only communicate these broad issues of conservation, but can also highlight the aesthetic value of scientific research itself. I sincerely think that the science conducted on this voyage by these dedicated people has as much aesthetic and cultural significance as painting a mural, composing a symphony, or making a film.

Science helps us understand our relationship with the world. We human beings are not only connected to nature; we are part of nature. We never really left that animal kingdom and that vast evolutionary family tree. In a way, encountering other species is like meeting distant relatives. But while there is that kinship with the natural world, what I was filming and what the scientists were researching is also taking place in an environment that is not suited for humans. It really feels like another planet being down on the Southern Ocean at the Antarctic Convergence. You are reminded that the scope and scale of our planet is enormous, and yet everything is interconnected.

I wanted the film to capture both that sense of connection, and that grandiose sense of scale. If we can help to convey intellectual information in ways that are emotionally resonant, then it will stick with people – and then, maybe, they’ll do something about helping our planet. But they have to care first.

What advice would you offer to filmmakers, artists, and scientists based on your experiences completing this project?

My advice to all of them – filmmakers, artists, and scientists alike – is the same. In no particular order: Always be prepared to adapt; go where the evidence takes you; explain big concepts in simple, relatable terms. We are a storytelling species. Find the story in the data that you collect. Maybe it’s one, big story; maybe it’s several little stories. But stories speak to and stick with our fellow humans.

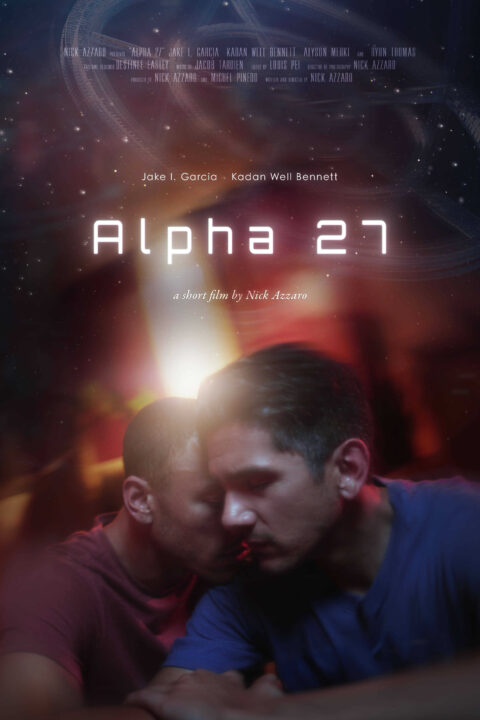

Nick Azzaro Bridges Worlds of Love Through Sci-Fi

Writer-director Nick Azzaro, who bridges his Italian roots with his life in Los Angeles, delves into the complexities of identity and belonging in his new short film, Alpha 27. The film embodies his personal journey through opposing worlds and highlights the power of human connections, capturing the tensions between different identities and the quest for a sense of home.

In our exclusive interview, Azzaro reflects on his return to the HollyShorts Film Festival and the emotional responses the film elicited. He discusses how resourcefulness and collaboration played crucial roles in achieving high production value despite budget constraints, and his hopes for how the film will resonate with audiences by conveying a message of resilience and the enduring strength of love amidst life’s uncertainties.

Cinemacy: It’s a pleasure to meet you, Nick! Congratulations on your short film Alpha 27 being selected to play at the 2024 HollyShorts Film Festival. What was it like showing your film there?

Nick Azzaro: Thank you! It felt amazing to be back at HollyShorts for the second year after screening my short film Retrieval in 2021. This time, I was lucky to have a primetime slot, and it was incredible to see Alpha 27 screened in front of a full audience in such a fantastic auditorium. The film looked and sounded perfect on the big screen!

It was my first time attending a public screening of Alpha 27, so it was incredibly rewarding to witness the audience’s reactions firsthand. You could feel the emotion in the room, and hearing people sob during the film was truly special. It was also great to be accompanied by other amazing films, and having many friends and collaborators show up to support made it even more memorable.

Cinemacy: You’ve said that Alpha 27 is a deeply personal narrative connected to your journey as an international filmmaker. Can you elaborate on how your own experiences influenced your vision for Diego’s character and his journey? Were there any particular moments or emotions you wanted to capture based on your own life?

Nick Azzaro: Alpha 27 is indeed a deeply personal film, and Diego's journey reflects some of the challenges and emotions I've faced in my own life as an international filmmaker living abroad. Like Diego, who is caught between two worlds (the life he's built on Earth and his origins in a distant space colony), I've often found myself navigating between different cultures, environments, and expectations in my career. Diego's struggle to protect what he has built while being recalled to his origins mirrors the tension I've felt between the hopes of forging a new path and the concerns of an uncertain future.

One particular emotion I aimed to convey was the fear of losing what you are blessed to have. In Diego's case, it's his life on Earth and his partner, and, likewise for me, it's the creative and professional journey I've embarked on and the close relationships I’ve built through the years. There's a sense of resilience in Diego's character, which I relate to—the determination to face challenges head-on and the hope that, despite the odds, you can protect what's important to you. Overall, Alpha 27 is not just a science fiction story, but also a reflection of my own experiences, fears, and hopes, translated into Diego's narrative.

Cinemacy: The central relationship between Diego and Marcus is portrayed so beautifully. How did you want their relationship to convey the themes of identity, love, and belonging in the film?

Nick Azzaro: Diego and Marcus’s relationship is the emotional core of Alpha 27. Their connection goes beyond the typical romantic bond; it's about two people who have found a sense of home in each other. Their relationship is a safe space where Diego can truly be himself.

In portraying their bond, I aimed to show how love can be a grounding force and that identity is not just about where we come from, but also about the connections we choose to nurture. Their love story is one of resilience, about the importance of finding belonging in the people we share our lives with, even when the world tries to pull us apart.

Cinemacy: What was the collaborative process like with your cast and crew while making the film?

Nick Azzaro: The collaborative process on Alpha 27 was a blend of trust, preparation, and creative synergy. With the actors, we spent a significant amount of time in rehearsals to develop the chemistry needed for their relationships to feel authentic. We worked together to find blocking that felt natural and ensured they were in the right mindset for their characters, especially knowing that our time on set would be limited. We workshopped the intentions behind each scene, making sure every emotional beat was clear. I trusted the actors completely, and they delivered touching performances, sometimes even nailing it in a single take, which speaks to their talent and preparation.

On the crew side, I was fortunate to work with many familiar faces. Most of the crew had been with me on previous projects, which made the process smoother and more efficient. My longtime collaborator, Destinee Easley, designed the costumes, helped as an acting coach, and served as a second pair of eyes while I was juggling both directing and cinematography. We had extensive discussions about the film’s color palette, and she selected outfits that perfectly matched the emotional tone and visual style we wanted to achieve.

I also brought back composer Jacob Tardien and sound designer Ugo Derouard, who had worked with me on Retrieval. Their contributions were invaluable once again. They not only understood my vision but also brought their own creative insights, elevating the film to a whole new level. It was a true team effort, and I’m grateful for the dedication and talent everyone brought to the project, including the many crew members who volunteered their time and energy.

Cinemacy: The film contrasts Earth and Alpha 27 visually and thematically so exceptionally. How did you and your production team approach the design of these two worlds?

Nick Azzaro: Designing the contrasting worlds was a critical part of the storytelling in the film. Even though we never get to see Diego’s life on Alpha 27, I wanted to visually and thematically represent the differences between these two environments, reflecting Diego’s internal conflict. For the house, I wanted to create a warm, inviting environment that reflects Diego’s sense of home and belonging. I used natural, earthy tones and soft ambient light to evoke a sense of comfort and familiarity, underscoring the emotional connection Diego has to his life there, especially with Marcus.

The goal was to make Earth feel like a place where Diego’s identity has flourished, contrasting the colder, more sterile futuristic environments that remind Diego of his colony. The immigration facility and the departures bay were designed to feel oppressing, stark, and clinical. I leaned into a more stylized color palette, using greens and blue tones to evoke the distant, almost alienating nature of the space colonies. The lighting was deliberately harsh and artificial, creating a sense of detachment and unease. I wanted the audience to feel the emotional distance Diego experiences when he’s preparing to leave for Alpha 27, making his internal conflict more palpable.

Being both the director and the cinematographer on the film gave me a unique advantage in having full control over my creative vision. This dual role allowed me to seamlessly align the visual storytelling with the emotional and narrative beats of the film, ensuring that each scene visually reflected the mood and themes I wanted to convey. It also facilitated a close collaboration with other departments, ensuring that every element was perfectly in sync with the film’s overall aesthetic and tone.

Cinemacy: What were some creative solutions you used to achieve the high production values despite budget constraints?

Nick Azzaro: From the beginning, I knew the goal was to create an intimate film rather than a sci-fi spectacle, which led to several creative choices that helped us achieve a higher production value despite the very limited budget. I chose the 4:3 aspect ratio specifically to favor close-ups and performances over elaborate establishing shots. I wanted the audience to stay close to Diego, experiencing what goes on in his mind throughout the film, and only focusing on the world around him when it was essential to the story.

Lighting played a crucial role in conveying Diego's emotional state, with brightness and color carefully selected to reflect his feelings in each scene. We scheduled our shooting days carefully, prioritizing scenes that required more elaborate setups to ensure we had the time and resources to execute them properly.

To achieve the futuristic visuals of Alpha 27 within our budget, I leaned on extensive VFX work. I used visual effects not only for the detailed holograms, but also in more subtle ways, like painting out equipment or enhancing existing set elements. This approach allowed us to achieve a polished look without breaking the budget, ensuring that the end result stayed as close as possible to my original vision.

Cinemacy: You describe Alpha 27 as an ode to the enduring power of love and human adaptability. What message do you hope audiences take away from the film?

Nick Azzaro: The film explores how, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges (like being forced to leave behind everything you've ever cared about), love can remain a constant, grounding force. Diego’s journey is a testament to the idea that while external circumstances may change, our connections and emotional bonds have the strength to transcend those changes. I want viewers to reflect on how love and resilience can guide us through life’s most difficult moments, offering hope and a sense of purpose even in the midst of uncertainty.

Cinemacy: How do you view the role of indie filmmaking in today’s cinematic landscape, especially in the context of competing with major studio productions?

Nick Azzaro: Indie filmmaking offers a platform for originality and diverse storytelling. It provides a bigger opportunity for talented voices to emerge, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, fostering inclusion and diversity in ways that larger studios sometimes overlook.

The budgetary constraints of indie films encourage creative problem-solving, pushing filmmakers to think outside the box, and leading to innovative and unique narratives. One of the greatest advantages of indie filmmaking is the creative control it affords, allowing filmmakers to craft more personal, authentic stories that resonate on a deeper level with audiences. Personally, I enjoy both indie and studio films, and I believe each has its strengths.

While indie films offer the freedom to tell more intimate and original stories, studio films provide the resources to reach wider audiences. I would love to be part of both worlds, bringing the lessons and creativity from indie filmmaking into larger productions and vice versa.

Cinemacy: In your opinion, what are the most important qualities or skills that indie filmmakers should develop to succeed in a competitive market?

Nick Azzaro: Adaptability is crucial. Filmmakers often face unexpected challenges, from budget constraints to last-minute changes, so being able to pivot and find creative solutions is essential. Inventiveness goes hand in hand with this; using limited resources to achieve a compelling story can set you apart.

Enthusiasm is also one of the most contagious and important qualities you can have. It drives the project forward and motivates everyone involved. Forget about trying to be fancy and focus on telling stories with heart and intention. Audiences resonate with authenticity, so putting genuine emotion and purpose into your work is key.

Finally, don’t be afraid to try new things! Embrace that spirit of exploration, and you’ll find that taking risks can lead to the most rewarding experiences and opportunities.

Cinemacy: How do you balance staying true to your creative vision with the practical realities of indie filmmaking, such as budget limitations? What advice do you have for filmmakers navigating this balance?

Nick Azzaro: It’s a delicate blend of realism and creativity. It's important to be realistic with your vision and expectations. When you're approaching a project, it’s common to start with a wishlist that includes all the big, fancy ideas you can think and dream of. But once that’s done, you need to strip it down to the core of the story and what’s best for it, considering what’s actually achievable with the resources you might have.

That said, don’t let limitations hold you back. Instead, use them to your advantage. Often, constraints force you to think outside the box, leading to creative solutions that can be even more effective than the “regular approach.” Limitations can push you to discover new ways of telling your story that are not only more practical but also more original and impactful.

My advice to filmmakers is to embrace these constraints. Be open to adapting your vision without compromising the heart of your story. It’s not about what you can’t do, but about making the most of what you can do.

'Going Varsity in Mariachi': Competitive Teens Perform Their Hearts Out

The best mariachi musicians perform confidently, expressively, and loudly. High school students, on the other hand, tend to be insecure, awkward, and uncertain about who they are and what they want to be when they grow up. Premiering at this year's Sundance Film Festival, Going Varsity in Mariachi is a look at the world of competitive high school mariachi teams who compete to win state championships. The film is joyful, expressive, and fun to watch. It will delight fans of sports and music documentaries (think Netflix's Cheer or Apple TV+'s Boys State) as well as mariachi music (such as myself).

As we learn, the main location for competitive mariachi music in the U.S. is Texas. Going Varsity in Mariachi begins by stating, "In Texas, over 100 public schools compete in state championships. The best are between the Rio Grande border between U.S. and Mexico."

The film begins, when else, but on the first day of school. (Timely enough, it's the school's first in-person semester since moving to online learning due to COVID). The documentary follows Edinburg North High School’s "Mariachi Oro" team. As we see, the school has a long history of success and awards. However, this year, the team is largely green and inexperienced. The task ahead of them is clear: to individually hone their instruments and quickly unite as a top-performing mariachi band in order to win their state's championship.

There's high school senior and varsity leader Bella, the head of the violin section who leads the team. We also meet the leaders of the trumpet and guitar sections, each needing to lead their sub-groups to success. The team's coach is music director Abel Acuña, who's led the school to many award-winning finishes in its history. On the first day of practice, he informs them that for the state championship, they must memorize 2 hours' worth of complex music and outshine all of the other highly skilled teams if they are to place, let alone win.

Watch the Going Varsity in Mariachi trailer here.

It's a tall task, especially considering the factors that are against them. Going Varsity in Mariachi follows the kids at home in their personal lives. Socio-economic factors such as low income pose problems for some kids (and is a reason some pursue mariachi, for financial scholarships to college). Similarly, the school also has to compete against other affluent schools with much higher budgets allocated to their programs.

The kids also struggle with just being kids. A suspenseful moment comes when one of the students, distracted by a new girlfriend, is kicked off of the team for missing practices. Panic sets in, as they're left without a leader for the guitar section with a quickly approaching competition. An even more compelling part of the documentary is the time we spend with a same-sex couple within the band. While young and introverted, they both own their sexualities and their feelings for each other, which is quite touching.

While all of the kids are at different confidence and competency levels, Going Varsity in Mariachi shows what unites them. Admirably, it's the deep connection they all have to their Mexican roots, which the music brings out. When the film shows them in their magnificently made costumes and performing together, you can see them come alive, proud of their heritage that the music expresses. It's hard not to get chills.

Directors Sam Osborn & Alejandra Vasquez do an excellent job of crafting a meaningful story arc within a full year spent with these students. It's a tough journey that they face together. The story doesn't shy away from showing the ups, and many downs, too. After one particular performance, a frustrated Acuña informs them that they've received the worst score he's seen during his time with the school.

But by the end of the film at the state championship, they are ready to compete. Seeing them in their uniforms, while concert-level tracking shots soar past them at their fullest power is electric. It will make you want to stand out of your seat and yelp your deepest gritos.

Going Varsity in Mariachi is a fun and rewarding watch. It's quite powerful to see how this special music will educate and inspire future generations to come.

This review originally ran on January 25, 2023 during the Sundance Film Festival

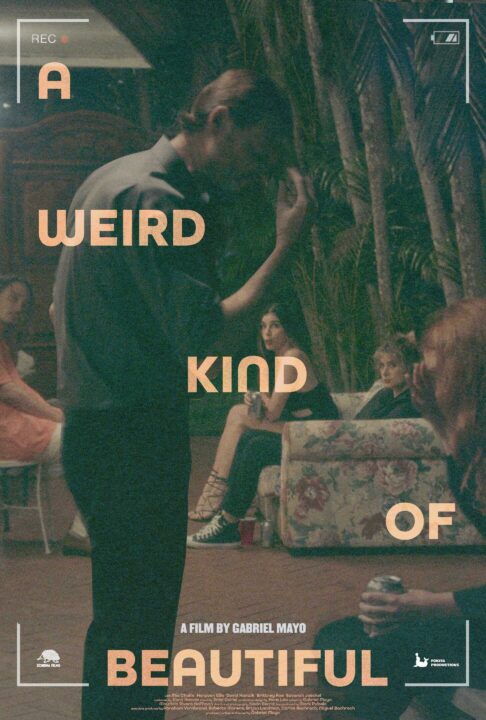

Gabriel Mayo Finds The Humor and Heartache In Life

Gabriel Mayo, a Peruvian-American writer, director, and producer hailing from Miami, has made a notable debut with his feature film, A Weird Kind of Beautiful. Crafted under the constraints of a micro-budget during the pandemic, Mayo's ambitious project showcases his ability to create compelling cinema with limited resources. The film, centered around a funeral and a long-overdue reunion, delves into themes of friendship, secrets, and introspection, making it an impactful directorial debut.

In our exclusive interview, Mayo shares insights into his filmmaking approach, blending drama and humor seamlessly while navigating the challenges of constrained budgets and unexpected hurdles. Along with the collaborative efforts of his carefully chosen actors and collaborators (who all wore many hats bringing this production to life), he has brought to life a film that will deeply resonate with audiences. Discover more about this promising filmmaker and his journey by reading our full interview.

It’s a pleasure to meet you, Gabriel! What inspired you to create your new film, A Weird Kind of Beautiful, and how did you bring the story to life?

Gabriel Mayo: I wanted to make my first feature but needed to make something that was in the micro-budget range, so I initially began to come up with ideas for something I could shoot in one location, with a few actors, and with a DV-CAM if I couldn’t get all the money. I began writing it during the pandemic, so shooting outdoors was also necessary.

I then began to figure out what kind of story I could tell within these parameters and had many ideas but once I came up with the main idea that we later see in a flashback – which I won’t reveal so as not to spoil the movie – I began to build the story around that. I wasn’t thinking too much about what I wanted to say, it was through the process of writing and making creative choices to create good drama that all these things I’d been thinking about seeped into the script.

The film's plot centers around a funeral and a reunion after eight years. What message or theme did you aim to convey through this story, and how did you balance the emotional weight of these scenes with moments of levity and humor?

Gabriel Mayo: I’d be lying if I said that I had an initial message or theme I wanted to convey. It was through the process of writing that I discovered these themes were in my head and I was sort of discovering how I felt about certain things as I was writing it. Yes, then it became obvious it was a story about friendship, the secrets that we keep from each other, and about how we look at the past.

And thank you for pointing out the moments of levity and humor, some people seem to miss those somehow. Once again, it wasn’t a conscious decision to inject humor. I have a dark sense of humor, but life to me is both dramatic and comedic, and can be both at the same time. I never understood the distinction between the genres, to me they feel the same. Sometimes you have more of one than the other, but it feels natural to me to have both.

What was your creative process in developing the film's visual style and tone?

Gabriel Mayo: I wanted to shift what the camera was doing throughout the movie. I knew we had to continually get different angles so we wouldn’t get bored of seeing the exact same setups for 80 minutes. Although this is a movie that can rely a lot on faces, I also wanted to see the set and this tiny little world the characters inhabit.

So in the beginning we use wider lenses and get to see more, as we progress we go up in focal length but only to a certain extent because we also needed the freedom to move the camera and if we had lenses that were too narrow we wouldn’t have had the space to shoot. I also wanted a deep depth of field for the majority of the movie so we could see characters in the foreground and background. And then towards the end we shoot mostly faces and get closer to the characters.

Indie films often rely on a tight-knit crew. How did you assemble your team, and what was the collaboration process like on set?

Gabriel Mayo: The first person to come on board was Mark Pulaski, who helped me produce the film. We needed people who were down for the cause. It’s a small indie movie, nobody is making what they should be making, they have to come on board because they love the project and want to be part of it and believe in it.

I wish we could’ve paid everyone what they should be making, but if we did, the movie wouldn’t have been made. So it was a matter of finding people that read the script and wanted to be part of the movie because it resonated with them in some way. It was a small production, so on set everyone wore multiple hats because we had limited resources.

How did you approach casting the film? What qualities were you looking for in the actors to portray these complex characters?

Gabriel Mayo: Casting and working with the actors was the most important aspect of this movie. I knew people had to almost believe the actors weren’t actors, but were the real-life people they’re supposed to represent. It should feel like you’re a fly on the wall this one evening with this group of friends. I was looking for very naturalistic acting.

To a degree I wanted it to have the same feeling like when I watched the movie Kids. None of them were actors and they seemed so real and unique. We dedicated a lot of time, more than a year, to casting and finding the right actors. Again, if we’re going to be staring at their faces for 80 minutes you better believe every word they say and action they take. It was challenging but we were lucky to find all of them.

How did you work with the cast to create authentic, compelling performances in a large ensemble environment?

Gabriel Mayo: We rehearsed the material for nine days before we shot anything. I had done a long casting process and some extensive readings with some of them prior. We spent the first few days of rehearsal going over the script line by line, making sure we were all on the same page about it. There were lots of questions and discussions that were part of the process but after the first few days we had covered a lot of ground.

We went in order and split up the script in the 8 or 9 different parts and focused on each one of these parts. After the first 4 or 5 days we went on set and started blocking. I think we finished blocking the last 10min of the movie on the last day of rehearsal because we were going in order and going over it again and again as we went along. By the time we got to day one of production they knew their characters really well, the dialogue, the blocking, etc… and they had also become really close friends in the process, which definitely helps. You see real friendship on screen.

What were your biggest challenges as an indie filmmaker in bringing A Weird Kind of Beautiful to life?

Gabriel Mayo: The uniqueness of the project made everything challenging because we had to do many things that are uncommon in an indie production. Finding five great actors who could deliver the performances you saw, given our resources, was incredibly hard. We spent a lot of time looking for them and, as I mentioned earlier, we went through a rehearsal period that was crucial and I had to fight for it because many people involved, not only did they not see the benefit, but didn’t see the necessity.

I’d get questions like, "Why can’t we rehearse for a couple of days? Why not just a week?" Making a movie is convincing everyone of your vision and of your way of doing things, and none of them had worked like that before. Shooting it too. It was a challenge to get all the setups we needed, and it was challenging for the actors to memorize so many lines and be ready to perform for ten minutes straight. The only way to address that was through preparation.

Do you have any memorable moments or behind-the-scenes stories from set?

Gabriel Mayo: Yeah, we had rehearsed the movie and knew how everything was going to play out, but there were two moments with Crux (who plays Eric) – one moment where he gets into an argument with Ivan, and later another between him and his fiancee – where something happened on those two nights where he tapped into something he hadn’t before and delivered an emotional performance that wasn’t even in the script and turned out to be better than I had originally imagined. Of course we had the night where it rained, our lights blew up and we couldn’t shoot for the rest of the evening, but who wants to hear the negative stuff?

Can you talk about the funding and budgeting process for the film? How did you secure financing, and what strategies did you use to make the most of your budget?

Gabriel Mayo: The funding was a combination of putting my own money, some investors came in, and then asking friends and family for money. Overall it wasn’t a huge budget, so between all those I was able to get enough to make the movie. It was still hard because we often didn’t have things that we needed. Many of us had to wear many hats, we had to ask favors, and tried to get what we could for cheap or nothing. The typical indie way of doing things.

What do you hope audiences will take away from watching the film, both in terms of its narrative impact and emotional resonance?

Gabriel Mayo: I wouldn’t want to impose an answer on the audience or tell them how they should feel or think. I’m often surprised to hear of people who have watched it, or read the script, because they all have their own interpretation. It’s always different how it resonates with them on an emotional and personal level. I do hope people find the movie engaging and it resonates with them in a way that makes them think about their own lives. Ultimately, like Albee once said, when people leave the theater they shouldn’t be thinking about where they parked their car. I agree with that sentiment and that’s the only thing I can hope for.

What advice would you give aspiring indie filmmakers looking to create their own feature films, based on your experiences?

Gabriel Mayo: Find a way to make something on your own with the resources that you have. Build a script around that. Stick to your vision and your way of doing things while at the same time be willing to accept other opinions, but only change what you had planned if the alternative gets you more excited than what you had originally planned. And learn how to write well before you shoot your first feature, you may not get another chance to make another one.

'Cuckoo' Review: A Shriek-Filled, Ear-Splitting, Bird Horror

I saw Cuckoo at this year's South By Southwest Festival in downtown Austin's historic Paramount Theatre, and it was a screening I won't soon forget. Not because it was my first time at the historic theater, which was beautiful in its ornate and old-school decoration inside. Rather, it's because the film–a body horror whose main monster is a shrieking carnivorous bird disguised in human form–was so absurdly bizarre and so ear-splittingly loud that it clawed and nested its way deep into my brain and ears.

The film stars Hunter Schafer (HBO's Euphoria, Yorgos Lanthimos's upcoming Kinds of Kindness) as Gretchen, a young woman whose remarried father brings her to a remote German Alps resort, much to her resentment. After her dad's weird boss Mr. König (Dan Stevens) shows interest in her mute half sister, she begins to understand that something is off. The strange noises she hears at night reveal a darker secret and danger threatening her.

Watch the Cuckoo trailer here.

Cuckoo is a fun time if you're looking for a mix of unsettling thrills and a playfully silly premise with a campy execution. It's definitely squarely a midnight movie versus thinking of itself as a serious horror film. I understand that this line is what the film's eccentric writer and director, Tilman Singer, enjoys treading. During the film's post-screening Q&A which the cast and director attended, Dan Stevens said that he saw Singer's 2018 horror film Luz and immediately agreed to be in this film without question. He did, however, appear to be just as flummoxed as the audience was after watching this deranged, off-center horror movie.

Leading the film is Hunter Schafer, who commands the film with strength and toughness, bloody and battered combatting the bird by the film's end. Cuckoo will best be enjoyed by those looking for a midnight movie. I know that when I think of Cuckoo, I'll hear every shrill, piercing squawk that rang in my ears every time the cawing creature preyed upon another unsuspecting victim. I'm still trying to wonder if the effect that I felt from the film was from true fear, or if it was just the shrill volume that the sound design operated at. I won't overthink it, as it would drive me to the point of the film's title if I did for too long.

This review originally ran on May 15th during the 2024 SXSW Film Festival

Spencer Jamison Explores Connection Through Serendipity

We've all experienced those moments in life where aimless, late night walks with friends or dates turn into long hours of laughing and discussing the most random of topics. These are the moments that indie filmmaker Spencer Jamison finds the beauty in, seeing connection through our shared serendipity.

In our insightful interview, indie filmmaker Spencer Jamison discusses her short film At Capacity which had its premiere at the LA Shorts International Film Festival. Spencer recounts how she drew from her experiences as an overwhelmed artist seeking hope and authenticity as inspiration for the film, along with challenges faced during production (managing multiple roles and a gas leak on set). Spencer emphasized the importance of collaboration and networking in the film industry, and gave invaluable advice for aspiring indie filmmakers. Read on for our exclusive interview with this bright, upcoming talent to keep your eye on.

Cinemacy: Hi Spencer, it’s nice to meet you! Congratulations on the world premiere of your short film, At Capacity, at the LA Shorts International Film Festival! Can you tell us about the inspiration behind it?

Spencer Jamison: It’s great to meet you as well, Ryan! And thank you, it’s a pleasure to be interviewed by Cinemacy. Also, shoutout to LA Shorts for supporting the film… it was a bit surreal getting to celebrate with the cast and crew this past weekend… some of whom have known me my whole life.

I wrote At Capacity at a moment in time where I was extremely overwhelmed with the state of the world and trying to figure out my place in it as an artist and woman. I wanted to create something with hope, something a bit sweet. But also a film that would spark a dialogue about how we can be better to one another… leading with tenderness and authenticity. It’s very inspired by those character driven 90s rom-coms, my appreciation for The West Wing, and the whimsical heart of Korean Dramas. Fortunately, my big brother and fellow filmmaker, Jai Jamison, and a close family friend, Ron Forbes, believed in the script so much they came on board as Executive Producers to help bring it to fruition!

Cinemacy: As an indie filmmaker, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced during the production of this film, and how did you overcome them?

Spencer Jamison: Production was fairly smooth (thank goodness!) once we brought on the help of Macy West and her production company, Mad Box Made. I’m currently based in Los Angeles and we were planning to film in my hometown, Richmond, VA. Macy was incredible because she was there on the ground making sure we assembled a really generous and skilled crew. With that taken care of, the most challenging aspect of production was wearing multiple hats and splitting my focus.

I’d written these dialogue heavy scenes in multiple languages, was also discussing blocking, camera setups, in and out of hair and makeup, doing collaborative revisions with my cast… it was a lot, but I honestly loved it and want to do it again. My main goal at every step of production was I wanted the world of At Capacity to feel warm and lived-in. This meant truly trusting that the cast and crew had my back and allowing folks to expand into their individual roles.

Cinemacy: One of the things that I was so taken by while watching was how the story explores themes of connection and serendipity. How did you translate these abstract concepts into visual moments in the film?

Spencer Jamison: There’s a specific visual moment at dinner where the camera slowly zooms in on Mia as she reveals to Ari that she feels like she’s stuck in a corner sparring with fear, anxiety, and rage. The camera lingers on her until Ari says, “Would you rather be pushed off a cliff, or with your own parachute in tow, choose to jump?” She doesn’t answer the question… but the question does give Mia some reprieve. She starts to breathe.

This is when we’re catapulted away from the restaurant into a more liberating and whimsical moment walking the canal in Shockoe Bottom. Having grown up in Richmond, I already knew it would be one of the main locations. I wanted to capture those serendipitous late night walks with friends or dates, where you spend hours laughing and discussing the most random topics.

Cinemacy: Were there any unique or memorable moments from the filming process that unexpectedly impacted the film's final cut?

Spencer Jamison: On our last day of filming… we had a gas leak… *insert yikes emoji* *sideways laugh-crying emoji* *upside down smiley face* Luckily, we caught it early, were able to air the location out, made sure everyone was okay, and had already created a plan to get the coverage we needed for the rest of the day. But it did mean we had to be really precise and ditch a couple of our setups.

We approached the restaurant scenes with an urgency that I actually believe aided in the acting for both me and Jake (Ari). Also I have to say… Jake is brilliant and hilarious and had some great adlibs and dialogue changes that elevated the film and 100% made it into the final edit.

Cinemacy: Working with a limited budget is a common constraint for indie filmmakers. What strategies did you use to ensure high production quality without breaking the bank?

Spencer Jamison: Again, I cannot thank my line producer, Macy, enough… She was so thoughtful in her budget and hiring that I knew going into filming we would be in great shape. Also fortunately, my brother was one of the editors, so we both deferred our payments for the various roles we took on in this production to make sure cast and crew were taken care of first. Which I mean is pretty common for filmmakers who really want to get their films made! I’m just very grateful for the crew in Richmond who have worked on a ton of big projects and took the time to contribute/work on At Capacity.

Cinemacy: How did you cast the roles of Ari, Maxine, and Audre? What qualities were you looking for in your actors?

Spencer Jamison: From the jump I wanted to work with my classmate from the Yale School of Drama, Jake Ryan Lozano. He was one of my first scene partners and has now become a great friend. We have immense trust in each other and I knew he would bring the wit, charm, and chemistry I needed to make us fall in love with both characters.

Zainab Bari (Maxine) is the sister of one of my best friends (Hey Binta!) and a fellow James Madison University alum. She’s a gifted director, writer, and actor in her own right and I’d been looking for an opportunity for us to work together. Plus, we look like we could be sisters.

We held auditions for the role of Audre. I have to thank our casting director, Anne N. Chapman, for introducing me to the incredibly talented, Joy Hana Park. The minute I saw her tape, I knew she would bring so much fun and nuance to this character in a short time. Now, we’ve become great friends and she’s like a little sister.

Cinemacy: What advice would you give to aspiring indie filmmakers who are just starting out and looking to get their films noticed by festivals, such as the LA Shorts International Film Festival?

Spencer Jamison: The festival circuit is hella unpredictable, so my biggest advice is to be centered in the purpose, intention, audience, and creative process of your film. You’ve got to have a strong “why” first and foremost. That will keep you grounded when rejections come and when those festivals in alignment with your work ultimately say yes!

More technical recommendations… rewrite, revise, and get the script (or treatment/concept if it’s more experimental) solid. It’s your roadmap. Be concise in how much time you need to tell the story you want to tell. Then assemble a team of people you trust to enjoy the process of creation alongside you. There’s no rhyme or reason to the way any of our paths unfold in this industry, but at the end of the day, we all want to be able to look at our work and be proud of the steps we took to birth our projects.

Cinemacy: Can you talk about the importance of networking and building relationships within the film industry, especially as an independent director? Who have you met along the way that has helped you get to where you are today?

Spencer Jamison: I’ve been fortunate to build a foundation of collaborators very organically. I met a fellow filmmaker last year, Caroline Renard, because we’d both recently made shorts. We bonded over our shared southern Black girl nerdom and desire to create opportunities for other Black women. She’s been a great holistic support system this year and now we’re planning a project that I’m going to produce and star in that she’s written and will direct.

Another incredible friend and mentor I have is Kaitlin Fontana whom I met through my brother. I took her screenwriting class and whew… my voice as a writer and skillset as a filmmaker have grown immensely with her trust and encouragement. I was recently the 1st AD on a short film of hers. “Networking” should feel nurturing. For me, it’s more important to genuinely enjoy each other’s presence than to pursue relationships with transactional intent.

Cinemacy: What pivotal moments or projects would you say significantly shaped your path as a filmmaker?

Spencer Jamison: I’ve been extremely driven my whole life and always believed I had a healthy relationship with the pursuit of achievement or success. But when the pandemic happened and we were all forced to pause/take stock, I faced burnout coupled with the brain fog of long Covid. This extended period of time was pivotal because it reminded me that caring for my physical, spiritual, and mental well-being is beyond essential. My approach to creation and collaboration is much more holistic now. It’s why I talk about nurturing one another and encouraging rest so often. It’s why I really want to lead by example on sets, in writers’ rooms, in rehearsals, in life… with a true sense of gratitude, play, and presence. I know now that my dreams as a filmmaker must work in tandem with living a good and full life.

Cinemacy: Are there any upcoming projects or future goals you're excited to share with us?

Spencer Jamison: I recently finished writing my first feature, a nerdy romantic comedy called Caught in the Middle of June. I’m now working on a second feature, a coming of age film dedicated to my grandmother, Marie. Hopefully one of them will be my feature directorial debut. I also have a sci-fi action short I’d like to direct. I wrote it for two close friends to star in with the need to unpack our relationships to social media and unhealthy trends.

For future goals, I desire to work in multiple capacities as a filmmaker and meet each project in whatever role it requires of me… whether that’s as a director, writer, actor, or producer. I’d also love to work with directors, writers, and showrunners I admire, travel, and create creative opportunities for others. Instead of the visual of climbing a mountain, I see my life and career as navigating waterways… sometimes the water will be still, some days there will be waves, but ultimately I’ll always have a healthy relationship to the changing of tides.

'Kneecap' Review: The Anarchic Rise of an Irish Rap Group

There’s a brash, in-your-face cockiness that the new dark comedy and music-packed film Kneecap carries itself with. The law-breaking, drug-snorting antics from the Irish rap group at the center of the film—played by the real-life hip-hop trio "Kneecap" that the movie takes its name from—are downright anarchic.

Further, the film doesn’t even care at times if you literally understand what's going on, as multiple rap numbers are delivered in their native Irish Gaelic language, requiring subtitles that the film sometimes, defiantly, does not provide. Despite this attitude, or perhaps because of it, Kneecap is a rebellious crowd-pleaser with a worthwhile message about preserving indigenous identity.

Rising From Belfast

The film fictionalizes the rise of the real-life Irish hip-hop group “Kneecap” in their proud hometown of Belfast. Naoise (Móglaí Bap) and Liam Óg (Mo Chara) are Northern Ireland hooligans who grow up selling club drugs and running from the cops. When Liam gets caught one night, a disillusioned music teacher, JJ (DJ Próvai), is tasked with translating Liam's Irish Gaelic into English. We learn that Liam's defiant use of his native Irish language was instilled in him by his father, a small-town crook now on the run (played by Michael Fassbender).

JJ realizes that Liam's commitment to his mother tongue, along with his original, cocky lyrics, aligns with his own values and inspires him to record the band. The trio—Liam, Naoise, and JJ, now known as DJ Próvai—begin recording songs that defiantly speak out against the country's harsh laws, drawing unwanted attention and catapulting them into the spotlight.

Beat-Driven Rebellion

Kneecap is anarchic, foul-mouthed, and ungovernable. And also, it's entertaining as hell. It's also more of a crowd-pleaser than I expected. Written by Rich Peppiatt along with Kneecap stars Móglaí Bap and Mo Chara, the film brings a unique story and style. Director Rich Peppiatt, in his first credited feature film after a Kneecap music video, injects electric energy and style, making for a visually captivating experience.

Director of Photography Ryan Kernaghan (Ted Lasso, Belfast) delivers sensational camerawork, with a full-on music-video approach, featuring hand-scribbled lyrics that bring the songs to life. Editors Chris Gill (American Animals) and Julian Ulrichs (Sing Street) create a kinetic, wild energy that the movie thrives on.

A Defiant, Musical Riot

And of course, the music is massive fun. Electronic club beats underscore Kneecap's in-your-face raps sensationally. Even if you can't understand the lyrics (or find it hard to read the onscreen translations), you don’t necessarily need to, as the emotion and energy are what are most important.

Kneecap is a riotously fun movie that captures the spirit of rebellion and cultural pride. As Michael Fassbender's wise, country-loving character says to the Kneecap lads, "Every word of Irish spoken is a bullet fired for Irish freedom," a sentiment that resonates deeply throughout the film.

Christine Handy and Ziad Hamzeh Connect Through Catharsis

What do you do when tragedy befalls you? If you're Christine Handy, who battled a breast cancer diagnosis, you bravely share your story to as many people as possible so that others may heal through connection. "Honest and courageous storytelling allows others to feel less alone. Sharing stories of great difficulty promotes connectedness," Handy says in our interview. Handy courageously put her own story into Walk Beside Me, which would become a best-selling novel. Now, she has overseen the adaptation of that novel into a feature film, Hello Beautiful, which she served on as as executive producer.

Cinemacy had the distinct pleasure of talking with Christine Handy as well as Ziad Hamzeh, who wrote the screenplay and directed the film. Read on to learn more about this poignant film, which captures the courage and resilience in the face of illness and despair. Christine and Ziad dive into their shared creative journey, inspirations, and challenges faced in bringing this deeply moving story to the screen.

Christine, what inspired you to adapt your best-selling book Walk Beside Me into this film? What were the earliest challenges you faced during this adaptation process?

Christine Handy: My inspiration to turn my book, Walk Beside Me, into a full feature film came from my own experiences seeking films during my cancer journey. Not only did I become frustrated with books that portrayed a cancer patient's journey, but I also became more fearful while watching popular cancer films. After completing my chemotherapy, I knew that if I could write the book, I would not stop until a film was made.

Of course, those were just dreams, but if you know me, you will know that I have a lot of grit and determination. I respect "No's," but they don't stop me. The earliest challenges still face me today. I am not in the film industry, so each step of the way has been fraught with uncertainty and tremendous hurdles. But we keep going, especially when it involves helping others.

Ziad, this film, Hello Beautiful, explores themes of courage, friendship, and love amidst tragedy. What excited you about the original story, and what did you want to add to ensure the visual and emotional themes captured the beauty and ugliness of illness and despair?

Ziad Hamzeh: Christine Handy is a remarkable woman, and her story is one of tremendous courage, determination, and love. As I read the novel and developed the screenplay, tears often burned my cheeks, because the emotions were so strong, on so many levels. I was determined to bring to audiences what I found so compelling in Christine’s story. She and her family were tested against the most extreme circumstances, and they did not give up. It was a transformational journey for all of them.

To do justice to their stories, it was important to highlight each characters’ perspective and struggles. I was assisted greatly in this area by our Director of Photography, Terrence Hayes. The visual tapestry he created effectively communicated the contrasts of intimacy, urgency, and vulnerability that mirrored the internal struggles of the main character. Also integral to communicating the emotions visually was our Production Designer, Layla Calo-Baird. She understood that the environment is also a key character in the film. We began at the pinnacle of happiness and success and fell to the depths of hell. The environments she created reflected all of that.

Together, our team created a visually stunning environment that externalized the variety and depth of emotions our characters were experiencing. Finally, the emotional environment was elevated even further by the exquisite compositions of Marco Werba. His music enhances every moment of the film. The collective expertise and tireless efforts of our entire team resulted in the creation of an engaging, heart-felt, and inspiring film.

Christine, could you elaborate on the decision-making process behind selecting Ziad Hamzeh as the director for Hello Beautiful? What qualities did you see in him that made him the right fit for this project?

Christine Handy: Ziad Hamzeh, from our first introduction, has been a champion for this story. It is not because it’s my story, but it is a story for all women that Ziad recognized. Because breast cancer is on the rise, particularly in younger women, I needed a partner that would get through all of the stumbling blocks with me. Ziad, like myself, has a great sense of tenacity and determination to help others. He brings passion to his projects as well as decades of experience. Ziad and I instinctively trusted each other from the beginning. We used the same entertainment lawyer to seal the agreement in 2018 and since that moment, we have not stopped working on this project.

Ziad, Hello Beautiful navigates through emotional and visual chaos while portraying decency in darkness. What early work did you do to conceive these contrasting elements into the visual style of the film?

Ziad Hamzeh: All of my work, both in theater and film, embraces the basic human experience. This requires knowing each character intimately. To accomplish this, I create a unified vision derived from the environment, economic status, and engulfing need of each character. This deep understanding of each character guides the development of the story and maintains consistency and authenticity throughout the project.

Also essential is contrast. I learned early in my career that contrast really matters. Most would agree that without pain, we cannot fully understand joy; and without darkness we cannot fully appreciate the light. It is the contrasts in the characters’ lives that enable us to genuinely understand and connect with them and their experiences.

I take my responsibility very seriously, because actors depend upon the director to ensure their performances deliver truthfulness and authenticity. So it is essential for me to work from a platform where humanity and human experiences are at the center of the story. This approach has always enabled me to deliver honest and compelling stories.

Christine, as someone deeply connected to the story on a personal level, what was it like for you to be on set during the production of Hello Beautiful?

Christine Handy: It was a dream come true to be on set during the production of Hello Beautiful. However, we were not portraying the most flattering parts of my life or the easiest. This film sheds light on the pain that entire families go through during cancer trials, bringing up deep pain. There were a few intense scenes that I purposely did not show up on set for. One scene in particular is still hard for me to watch even though I experienced it ten years ago. When you watch the movie, think of the table scene; that was the day I stayed home.

Ziad, in a film that explores such intimate and challenging themes, how did you work with the actors to bring authenticity and depth to their performances?

Ziad Hamzeh: The intimate and challenging themes in the film required us to explore the story and the characters in a truly honest and authentic manner. Perhaps the best preparation for me relative to supporting the actors’ understanding of the characters and the themes of the story is that I wrote the screenplay. As I did, I felt the characters’ emotions, spoke their words, ached with their pain, and reveled in their joy. So when it came time for me to rehearse with the actors, I had already developed a deep understanding of each character and theme.

Fortunately, our talented cast came well-prepared for their roles. Their skills and professionalism were extraordinary. They had researched their characters, the global crisis of breast cancer, and many other elements. My responsibility during rehearsals was to ensure they came to understand their characters even better than I did. I worked closing with them in a variety of formats and listened attentively to their queries and requests. They prepared diligently and collaboratively and brought their passion for the project to the set every day. Each and every moment of the script was explored, dissected, and questioned in order to deepen the actors’ understanding and thus strengthen their performances.

What were the biggest challenges you each faced while making this movie? What were the most unexpectedly rewarding moments?

Christine Handy: The biggest challenges related to funding and our limited budget. We started production during the strike, which also added to our restraints. Ironically, the most rewarding moments involved the same budgetary constraints that invoked such peril. The slender budget forced each and every person to work harder and with greater professionalism. This elevated the set and brought all of us closer. We all shared an underlying drive to make this film exceptional, even with the restrictions.

Although many of the scenes required intense emotional acting, we did not have time for breaks. Our schedule demanded an intensity that was felt by all. Quite literally, the entire community rose to the occasion. Other unexpected rewards occurred when the actors gave much more than I expected. I cannot wait for the world to see Tricia Helfer's performance in this movie. There is also a buzz going on about Sara Boustany and Tarek Bishara's performances as well. The casting for this film is perhaps the greatest reward so far.

Ziad Hamzeh: Challenges in filmmaking are common from the moment you begin development until you complete the project. In our case there were three significant challenges. First, the Screen Actors Guild was striking, so we had contractual terms to negotiate with SAG. Fortunately, we were granted permission to proceed. Second, there were a variety of complications with the set. Our Producer, Michael Espinosa, took on the burden of resolving most issues, so I could focus on my role as director. Third, as with many productions, the biggest challenges were time and money. The limitations of our budget required us to complete the filming in fewer days than we would have preferred. We shot in only 18 days, when ideally we would have had double that.

As for unexpectedly rewarding moments, I was reminded daily of the exceptional talent and determination of our cast and crew. It was an honor, a privilege, and a joy to work with them, and the quality of the film is evidence of their ability and commitment.

Another unexpectedly rewarding moment occurred on a day when Tricia Helfer was slated for a particularly demanding day - several scenes and costume changes, long hours, and lots of emotion. She is incredible, focused, humble, and patient. Between scenes she would listen to music in a quiet space to find her center so she could harness the energy and emote the feelings required of her. The seriousness and dedication she invested in the role was all awe-inspiring. That day she brought the cast and crew to tears, myself included. Witnessing the impact you hope an audience will experience come to fruition on set is truly humbling and enormously rewarding.

What do you both hope audiences take away from Hello Beautiful, both in terms of its narrative impact and its emotional resonance?

Christine Handy: Honest and courageous storytelling allows others to feel less alone. Sharing stories of great difficulty promotes connectedness. I felt very alone in my diagnosis. I was younger than most women I had known with the disease and I was blindsided by my diagnosis. It was in those early darker moments that I vowed to share my story if I survived. I desperately did not want others to feel such emotional fear and paralysis. My greatest hope is that this film helps as many women as possible feel less alone. I want to champion the importance of community in breast cancer while trying to negate the loneliness of the disease. If this narrative accomplishes that, then the emotional resonance will be one of togetherness and not separateness.

Ziad Hamzeh: Since the beginning of time, humans have shared their stories with others. From ancient cave drawings to the modern spoken word, humans have sought validation from others for what they have experienced, loved, learned, and lost.

Early in my career, I was an actor. It was at UMASS Boston, under the guidance of Lou Roberts and Susan McGinley, that my competencies as a director began to evolve. Those who understand the approaches of Stanislavsky and Brecht may find their methods in opposition, but for me the combination of the two seemed natural and appropriate.

Brecht wanted his audiences to be inspired to action. He wanted them to erupt from the theater with the determination to do something as a result of what they had witnessed. His goal was to effect positive change.

In contrast, Stanislavsky sought to optimize the cathartic experience within the theater. This allowed his audiences to relieve themselves of the emotions they were feeling in the moment instead of bringing them outside the theater.

I wanted our audiences to feel the cognitive dissonance of the two approaches - to feel the heightened emotions of the characters and also to feel inspired to effect change. No one should die of breast cancer. We need a cure.

Let’s get to know you both better! Where are you both from and where do you currently reside?

Christine Handy: I am from St. Louis, Missouri. I then moved to Dallas, Texas to go to a college called Southern Methodist University. I ended up staying in Dallas for over 25 years. I raised my two sons there. In 2015, I moved to Miami, Florida to live close to the beach and get a fresh start.

Ziad Hamzeh: I was born in a small farming community south of Damascus, Syria. I immigrated to the United States in 1979 after spending a few years in Paris. Presently, I live near the ocean with my wife and sons about 20 miles north of Boston, Massachusetts.

What are your favorite films, who are your filmmaking idols, and dream collaborators?

Christine Handy: Some of my favorite films are older films. I loved John Candy, so anything with him in it, like Uncle Buck. But I also enjoy watching movies based on true stories, such as The Boys in the Boat and CODA. Recently, I watched Ordinary Angels starring Hilary Swank. It is a story of tragedy and hope, as well as a refreshing reminder of the importance of compassion.

My dream collaborators are those production houses that can take Hello Beautiful to the largest audiences. I believe, with everything that I know to be true, that this film will ignite hope. For that reason, I am deeply committed to continuing to work to reach as large of an audience as possible. There is no limit to what we can accomplish when we believe in ourselves and our projects.

Ziad Hamzeh: As you might imagine, I enjoy many films, admire many filmmakers, and would love to collaborate with some of the legends of our industry. The common denominator is that each honors the essence of humanity - what we are, what we feel, and what we aspire to be… These speak to me; their works inspire me. In truth, every human being I've encountered has contributed in some way to my understanding of good storytelling.

In terms of a dream collaborator, that is and always will be my wife. When we were young, she taught me English, and we created The Open Fist Theater together, an oasis in Hollywood for those who shared our passion and collaborative spirit. Forty years later, she is my North Star, my writing partner, challenging me to achieve the honesty and truthfulness I strive for in all my projects.

What is one thing you’ve learned as a filmmaker that you think other filmmakers would benefit from knowing in starting their careers?

Christine Handy: I do not consider myself a filmmaker, although I suppose I have now made one film. When making this film, I couldn't understand how any films truly get completed. The obstacles seemed so great, not just for small budgets but I imagine for all budgets. I would simply say that quitting should not be an option. Only the ones who stick it out in the difficult messes get it done. So keep going.

Ziad Hamzeh: I have learned countless lessons as a filmmaker, and I’ll share just a few. First, human beings are continually evolving, so we must continue to learn from and with each other. That means listening with an open mind to all opinions and respecting all perspectives. Second, working as a team is important, but nurturing that team so it becomes an ensemble is even better. When your cast and crew know and care about each other, everyone’s experience on set is improved. Third, all egos must be left at the door. Only with kindness and compassion can a unified vision flourish.

What is one message that you would like to share with audiences about your work, your general outlook on life, that you are interested in further showcasing in your films?

Christine Handy: I would describe myself as a hope facilitator. It is not always easy to continuously talk about a story that is rooted in such pain. Yet, by doing so, it can bring a sense of community to a disease that is so isolating. Whether through a book, a film, social media, behind a podium, or even one-on-one, talking about struggles on a very personal and vulnerable level invokes connection. The purpose of this film is to show a very accurate portrayal of a disease that is on the rise. Not to show the disease as hopeless, but to model the importance of people showing up during illness and the truth of the human spirit's fight to survive. I believe deeply that this film, in particular the ending, has the ability to give tremendous hope.

Ziad Hamzeh: I believe the most valuable stories engage the viewer in the immersive experience of unpacking, scrutinizing, and embracing the human condition. Much of my work is a reflection of who I am, what I value, and how I see the world. I seek to contribute positively through my art even as I dare audiences to look in the mirror, think differently, and choose alternative paths.