Muneeb Hassan Shines A Light On Closeted Love

Many people view being closeted as entirely negative. Still, filmmaker Muneeb Hassan sees it in a different light—one that is often shaped by the relationships and cultural expectations of others. In his new short film All the Men I Met But Never Dated, Hassan explores how the decision to remain closeted can express love, particularly toward more traditional family or community values. "I wanted to capture the nuance that, for many, the closet can serve as a safe space rather than just a place of oppression—a perspective often overlooked in the Western world."

Read on to learn how Hassan brought this delicate subject to life, from portraying complex emotions to casting his two lead actors. He also discusses the unique challenges of being an independent filmmaker and what he hopes viewers take away from the film. "I hope viewers leave with a deeper empathy for those navigating similar paths and a greater appreciation for the courage it takes to honor oneself, even when doing so requires balancing cultural expectations."

Follow All the Men I Met But Never Dated on Instagram for more updates.

All the Men I Met But Never Dated is inspired by the unspoken experiences of closeted Gay Muslims. What motivated you to pursue this story, and how did you envision bringing it to life on screen?

Muneeb Hassan: The motivation for this story came from the need to shed light on a reality that is often hidden and misunderstood—the unspoken experiences of closeted gay Muslims who navigate the complexities of identity, faith, and family expectations. I wanted to capture the nuance that, for many, the closet can be a safe space rather than purely a place of oppression, a perspective often overlooked in the Western world. For many men, Muslim or not, the closet represents a complex balance of identity and safety.

Interestingly, after a screening, some audience members from Fort Worth, Texas—even self-identified cowboys—shared that they saw themselves in this story and felt validated by its message. Hearing that it’s okay to date someone in the closet and that this experience can be relatable across diverse backgrounds reinforced my vision. I aimed to bring this story to life with subtle, intimate visuals and restrained dialogue, capturing these journeys' vulnerability, resilience, and quiet strength.

Your film explores the complexities of love, identity, and familial duty. How did you balance these themes while developing the script?

MH: Balancing these themes was essential because they’re deeply intertwined for many people, especially those who feel divided between personal identity and family expectations. David Stokes, my co-writer, and I wanted to show that love, identity, and duty aren’t mutually exclusive but parts of a complex reality for someone like Ali. We worked to weave them naturally into Ali’s story so his decisions and conflicts would feel genuine and universally relatable, even if the specifics are unique to his experience.

David Stokes: Muneeb wrote the first draft, and I took over the writing from that point and did all of the subsequent drafts. As the story was pretty much there, my job was to rewrite Muneeb's script to make it flow better, rewrite all of the dialogue so that it felt more realistic and authentic to the characters as well as some narrative changes that sped up the script and made sure that we always got to the heart of the scene and the emotions the characters were trying to convey.

Dialogue plays a significant role in your film. How did you approach writing those conversations to convey the characters' emotions?

MH: Dialogue is powerful, especially when exploring things that are left unsaid. For Ali and Oliver, we wanted conversations that were raw and honest but also reflective of the hesitation and fear that comes with vulnerability. I approached the dialogue by focusing on subtext—sometimes, it’s what the characters avoid saying that reveals the most about their emotions. Writing these moments was about balancing tension and intimacy to bring the audience closer to their inner worlds.

What challenges did you face in portraying Ali's internal struggles, especially regarding his decision to stay in the closet?

MH: Portraying Ali’s internal conflict was challenging because it’s a silent struggle that many people, especially from conservative backgrounds, can relate to but rarely express openly. It was about capturing his moments of isolation, self-doubt, and reflection without making them feel overly dramatic.

We relied on small visual cues and body language to communicate his tension, and I worked closely with Ahmed to capture the weight of these unspoken battles in his performance. Ahmed also brought his struggle into the character as a journalist and actor; he spoke not about his struggles but represented every single gay Muslim who prefers to live in a closet.

What qualities did you look for in Ahmed Shihab-Eldin and Jared P-Smith, the actors who portray Ali and Oliver, and how did you find the right fit for their roles?

MH: I was looking for actors who could embody the emotional complexity of their roles with authenticity. Ahmed’s real-life experiences and empathy made him a perfect fit for Ali; he understood the character’s depth and struggle.

With Jared, I needed someone who could bring warmth and openness to the role of Oliver—a character who contrasts with Ali’s guarded nature. The chemistry between Ahmed and Jared was essential, and their dynamic truly brought the relationship to life.

Can you talk about working with Cinematographer Nicholas Pietroniro on the visual style you wanted to evoke? And what did your editor, Wyatt Smith provide?

MH: Nicholas and I wanted to create a visual style that reflected Ali’s internal state—soft, intimate, and sometimes isolated. We used muted tones and close framing to evoke a sense of closeness and introspection.

Wyatt Smith, ACE, our editor, brought an incredible sensitivity to the project. His precision in pacing and transitions helped amplify the emotional undercurrents without overstating them. He understood the rhythm needed to convey Ali’s journey subtly but powerfully.

As an indie filmmaker, what unique challenges did you encounter during production, and how did you navigate them?

MH: Indie filmmaking is always a balancing act between vision and resources, and with our modest budget, every decision had to be incredibly intentional. We had only 1.5 days to shoot—one day in Cold Spring and half a day in New York City—so time constraints were a significant challenge.

We focused on meticulous pre-planning to make the most of every moment on set. I had a shortlist and storyboards ready. The passion and commitment of our cast and crew were essential; everyone was fully invested in telling this story, and that collective dedication allowed us to overcome our limitations.

How has this film influenced your perspective on your own identity and the stories you want to tell in the future?

MH: Creating this film has been an incredibly profound journey that’s challenged and reshaped my understanding of my identity. In exploring Ali’s character, I reflected deeply on my experiences, the intricacies of cultural expectations, and what it means to navigate the space between personal truth and family loyalty.

It’s awakened a stronger desire in me to tell stories that don’t just entertain but also illuminate the unseen struggles and resilience within underrepresented communities. I’m more driven than ever to bring forth narratives that honor the complexities of identity, belonging, and strength—stories that break down stereotypes and give voice to often overlooked experiences.

What do you want the audience to take away from Ali’s journey and his choices regarding his relationship with Oliver?

MH: I want the audience to understand that Ali’s challenging choices are rooted in love and a deep sense of duty. His story isn’t one of rejection or shame but rather a complex balance between personal happiness and familial loyalty, a theme that resonates across cultures.

I hope viewers leave with a deeper empathy for those navigating similar paths and an appreciation for the courage it takes to honor oneself, even when it means balancing cultural expectations. Ali’s journey shows that self-acceptance and family loyalty don’t have to be mutually exclusive—they are intertwined in ways that deserve compassion and respect.

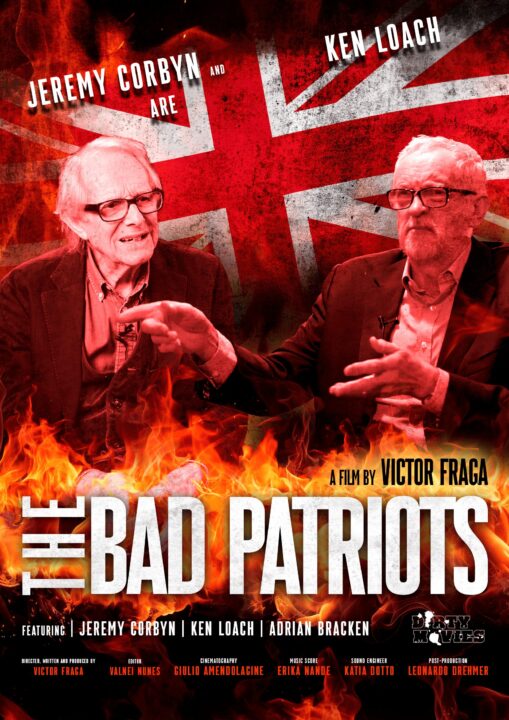

Victor Fraga Busts The Myth of Balance In Media

Born and raised in Brazil but has spent his entire adult life in the United Kingdom, Victor Fraga possesses a unique perspective on the political landscapes of both nations. Witnessing the erosion of Brazilian democracy beginning in 2016, he became acutely aware of the mainstream media's crucial role in both demonizing progressive leaders and facilitating the rise of the far-right. This realization prompted him to produce and direct The Coup d'Etat Factory, a hard-hitting documentary that exposes the manipulative tactics employed by the media. Now, Fraga returns with his latest film, The Bad Patriots.

In this exclusive interview, Fraga—also the founder of indie film publication Dirty Movies—shares insights into his new project, which collaborates with social realist filmmaker Ken Loach and former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. He also delves into his unyielding commitment to challenging the myth of "balance" in the British media. "It’s tragic," he asserts, "that the same shocking manipulation and censorship tactics I witnessed in Brazil are now rampant in the UK, the US, and other so-called 'developed' nations. Perhaps we're not as developed as we like to think."

It’s a pleasure to meet you, Victor! What inspired you to create The Bad Patriots, and what personal connections do you have to its topics?

Victor Fraga: I had previously made a film about media manipulation and censorship in Brazil, my birth nation. It was called The Coup d’Etat Factory. So, this topic has been close to my heart for a long time. After my film was finished, I realized that—contrary to belief—the UK is not quite a role model of media balance and democracy. The manipulation techniques are far more sophisticated here.

I first met Jeremy in 2016, when he was the Leader of the Labour Party, and I was campaigning against the coup that removed President Dilma Rousseff in Brazil. Jeremy has a close and personal association with Latin America, consistently visiting the continent and campaigning for international solidarity. His wife Laura is Mexican. He identified himself with my film so much that we did four or five panels together and became very close. I interviewed Ken three times in the past, and he, too, knew my work. So Jeremy and I insisted that he join the untitled The Bad Patriots.

You’ve mentioned witnessing the collapse of democracy in Brazil and the mainstream media's role in that process. How has this experience shaped your understanding of media's influence in the UK, particularly regarding figures like Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn?

VF: I have left Brazil, yet Brazil has never left me. I feel a duty towards both countries, where I was born and raised, and where I have resided for roughly a quarter of a century. These two films resulted from my activist and artistic commitment to both nations.

My experience with both countries is constant; one does not come after the other. I am intimately and consistently connected with both. I think I’m well-informed and have connections to influential personalities on both sides of the Atlantic, so I can comment on and compare the two countries.

Your films often explore themes of character assassination and censorship. How do you think the narratives around Loach and Corbyn serve as a microcosm of broader societal issues regarding free speech and dissent?

VF: Loach and Corbyn are much more vulnerable than the average citizen because they are well-known. Corbyn points out in the film that it’s much easier to attack individuals than ideas. The average British person might suffer micro gestures of censorship or perhaps even lose their job due to their political inclinations (in more extreme cases).

Very few people are subject to character assassination, defamation, and lawfare to the same extent as Ken and Jeremy, particularly the latter. The attacks are so fierce that despite being such outspoken and courageous people, they, too, have to self-censor on occasion. Freedom of speech is but an illusion.

Can you explain the central thesis of the documentary? What myths are you aiming to bust?

VF: The film's central thesis is that the British media are highly biased and hostile to voices vaguely critical of capitalism and the establishment. The UK is a very conservative country. I’m a pacifist, and I’m not a Marxist. Yet my political views and those of Corbyn and Loach are often viewed as “extremist.”

I set out to bust the myth of media balance in the British media, the facile pseudo-patriotism disseminated by the British establishment (including Keir Starmer’s rotten Labour Party), and the weaponization of antisemitism, among others.

How did you approach the research for this film, particularly in gathering diverse perspectives on Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn?

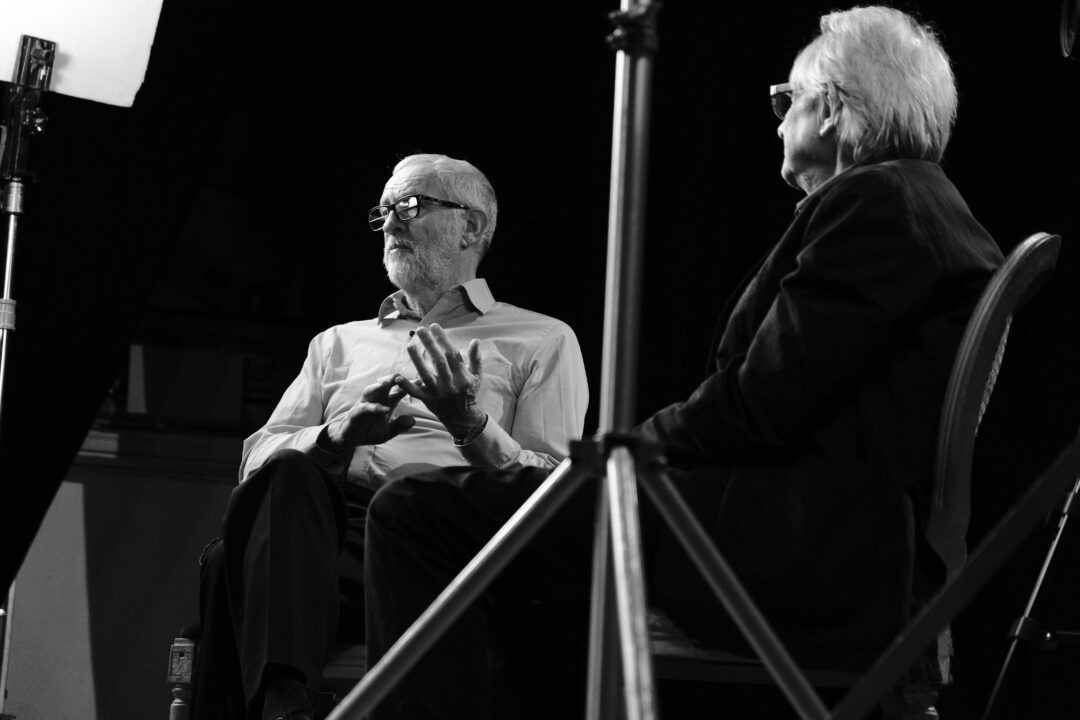

VF: Ken, Jeremy, and I met a few weeks before the shooting (which was done in a single day), and I asked them to collate anecdotes of media bias and censorship to which they were subjected. I researched newspaper articles that demeaned and insulted Ken and Jeremy - which wasn’t a particularly difficult job. There’s so much hate against these guys out there.

Finally, I was familiar with Ken’s filmography, which helped me structure the movie with his clips. It was a relatively simple process, a straightforward project. I would call it politically audacious yet aesthetically unpretentious (I’m not embarrassed by my microbudget and by exposing the informality of the movie, such as the failing microphone, which I intentionally chose to leave in the film).

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced while filming, especially regarding accessing sources or differing viewpoints?

VF: There were no significant issues. We are super grateful to our friends at Sands Studios, who provided their incredible facilities in kind. Christine Edzard and Olivier Stockman are committed to activist cinema—films that make a difference. Ken and Jeremy, too, were super open and relaxed.

Were there any surprising revelations or moments during the production that changed your perspective on the subjects?

VF: The most significant change came during post-production, on October 7th, when Hamas attacked, and Israel retaliated with the most shocking genocide in modern history. We recorded the film a few months before, and the topic was already present. I decided to make it much more prominent and close the movie with a pertinent reflection.

There were no major surprises during the filming. Instead, some of the anecdotes are hilarious in their absurdity, such as comparing The Wind That Shakes the Barley to Mein Kampf and Jeremt Corbyn riding a Mao Zedong bike.

Are there any particular moments in the documentary that resonate most strongly with the audience? Why?

VF: Hopefully, the part on Britain’s inability to self-reflect and recognize its past atrocities (the British Empire). The tub-thumping patriotism that our media disseminates is perhaps the most significant root cause for the defamation of progressive voices. Those who dare to challenge the establishment and refuse jingoism are not traitors. Quite the opposite: they are the ones who care about the average citizen. Hence, the ironic film title.

What are your plans after this project? Are there other topics or themes you’re interested in exploring next?

VF: I am currently a producer on a much larger project for a well-known filmmaker, a close friend of mine. Fingers crossed that comes to fruition. And I’m working on the third movie in the Dirty Media trilogy (the first two being The Coup d’Etat Factory and The Bad Patriots).

It features a very outspoken and energized Noam Chomsky in his penultimate interview before health issues prevented him from talking and writing. Maybe I will call it The Bad Jew.

Amanda Deering Jones and Kitty Edwinson Treat Addiction With Compassion

Addiction is a deeply complex issue, and it becomes even more challenging when a loved one is affected. Director Amanda Deering Jones and screenwriter Kitty Edwinson approach this sensitive topic with compassion in their short film Little Mother Lies, inviting audiences to engage with the realities of addiction more empathetically.

In the film, Amanda Deering Jones and Kitty Edwinson explore the intricacies of bringing emotionally charged scenes to life, aiming to foster a more nuanced understanding of recovery. Jones and Edwinson express, "If even one person leaves with a shifted perspective on their situation, we will consider it a success." Read on for our exclusive interview.

It’s a pleasure to meet you both, Amanda and Kitty! I’d love to hear how you first became involved with your new short film, Little Mother Lies. Kitty, being the screenwriter, when did this story’s idea first come to you? Amanda, when did you become involved with this project as the director?

Kitty Edwinson: Hi Ryan, it’s a pleasure to meet you! The idea for this short came from the feature on which it's based, Mother Lies. I found a letter my grandmother had written in 1955 to her sister’s psychiatrist describing what the sisters endured as children when they fled Russia during the 1917 Revolution. My mother did not know this story. I showed the letter to my sister and said, "There’s a movie in here."

Amanda Deering Jones: Thank you for talking with us! As a producer, I have been with the feature since 2020. However, at the end of 2022, we discussed creating a short as a proof-of-concept. At the same time, I had personal revelations about wanting to enter the directing seat in my career. The stars aligned, and I was able to dive in with this short.

What were each of you most excited to bring to the screen, and how did you approach these sensitive subjects?

KE: This story gave me a chance to portray the fallout of a horrific choice parents of addicted children often face and then play with what might happen if the son, in this case, caught even a tiny inkling of what that fallout was, how it was shaping the decision he’s making in this very moment.

We approached this by gradually revealing the extremity of the situation to the audience and then having the son and audience learn what the choice was at the same time. This way, the audience’s reaction would be compounded by caring how the son responds.

ADJ: Two things excited me from the feature that Kitty crafted. I wanted the world to meet these complex sisters. I always thought their dynamic was fascinating as well as deeply relatable. And I wanted to show a mother willing to face her darkest fears to save her son. Much thought and care was put into the story around what we wanted to highlight, poke at, and elevate in the world of addiction.

The same goes for the pitch material when we approached investors. Kitty did a beautiful job sculpting the dialogue around what was said and what wasn’t said. We only moved forward once we all felt the script was truly ready.

Kitty, what did you want to highlight when writing the roles of sisters Dorie, Marinka, and her son?

KE: I wanted Dorie to embody the fear, worry, and exhaustion of a parent in this situation, layered over with tension and ambivalence around being with her sister. Pascale Roger-McKeever did this brilliantly. I wanted Marinka, her sister, to be this mesmerizing force of nature who embodies the allure of the family’s particular approach to life while also dramatizing the destructive core of that same approach–Emilie Talbot did this brilliantly.

I wrote the son to be in the throes of heroin withdrawals, a state he’s familiar with while being in a situation that is literally foreign, suffering in this weird room. Elliott Thomas West perfectly captured the son’s curiosity, rising and falling with the waves of sickness and his primal need to escape while also being a beloved son who has not been lost.

Amanda, what was your process for casting these characters? Did you have specific actors in mind?

ADJ: We had actors in mind for the feature, but the short was a different beast. We brought on a brilliant local SF Bay Area casting director, Kim Donovan, and decided to look for local actors first. We lucked out for both of the sisters. Pascale Roger-McKeever and Emilie Talbot sparked us immediately. Elliott West from LA also quickly rose to the top as a standout.

Amanda, how did you approach directing actors in such emotionally charged scenes?

ADJ: Time is often more squeezed with a short, but I met with each of them individually because I wanted us to get to know each other as people first. I wanted to hear more about their process and how their brains work. This was supremely valuable going into the shoot.

I knew these would be tough roles, but I wanted them to feel they could lean on me for emotional support and to feel safe throughout the entire process. This preparation served us all as we navigated the hardest scenes, and in the end, they blew me away.

What were some of your biggest challenges in making Little Mother Lies as an indie film?

KE: My confidence flagged sometimes. On days when we hit some bump, I’d feel certain that the project would never come together, much less be superb. I had to work on restoring my faith. I was also worried about funding, which came together after all, but boy, that was a nail-biter.

ADJ: Kitty said it: Fundraising is high on that list. We approached investors and utilized crowd-funding. The great news is we got there, but it was a lot of work and a rollercoaster. Looking back, I realize that so much felt deeply hard while we were in it. Still, I am also blown away at the number of things that fell into place to support this project, particularly the incredibly talented people we pulled together.

Can you discuss your collaboration with the crew and how you brought everyone’s ideas together to shape the final product?

KE: We have been a tight bunch since the idea's inception for a short. We gradually honed our goals over the time the script was finalized so that by the time we had to shoot, Amanda could be the shepherd, as she says, and everything zipped together. The communicativeness and focus with the crew were a delight to experience.

ADJ: I care deeply about each person feeling they can contribute. You do this by declaring it from the start with your team and how you respond when they offer a thought or note. You will not take every idea, but if you’ve done your homework as a director, you will know what to take and what not to take. When I didn’t take a note, I at least acknowledged it and often explained my reasoning. Yes, this can be more work, but it creates a dialogue and builds trust. If we had not set this tone intentionally, we would have missed out on gold, and the short would have suffered.

Amanda, did you employ specific filming techniques or styles that were particularly effective for this story?

ADJ: In my research, I found an image from another film that I knew was the exact tone I was aiming for, and it became my guiding light. It utilized an anamorphic lens, and that cinematic feel was vital to convey a bit of mystery, a deep focus on the subjects, exposing their vulnerability, with a touch of absurdity and chaos at times.

Then, lighting was essential to bringing in all the conflicting tones; a warm background meant to tell us that there was love amongst the chaos, but blue lighting reflected the current state of the relationships. The opening scene has the sisters mostly isolated in shots, demonstrating how disconnected they are, but with a few wide two-shots for moments of connection. We were fortunate to utilize 2 Alexa Mini cameras for those isolated shots, allowing seamless filming where we could capture full performances with fewer takes.

What do you hope audiences take away from Little Mother Lies? Have you received any feedback that particularly resonated with you?

KE: People in recovery are all around us, and people struggling with addicted loved ones or addiction themselves are, too. Before we began shooting, crew members conveyed to me how important it was to them that this story be told. It has already generated critical conversations. This means everything to me.

I want the audience to come away with a deepened understanding of what being in this situation might be like from each perspective: parent, sibling, addicted loved one. I want them to soften or suspend judgment. If they do know something about addiction, I want them to gain the courage to have a different kind of conversation with people who matter to them (including themselves).

ADJ: Most feedback has been powerful and moving because it resonates. Like Kitty said, it’s sparked meaningful conversations at times. Each person's interpretation of the ending is unique, but they’ve certainly felt its weight with each viewing. I hope it creates more understanding for families struggling with addiction. If just one person walks away with a perspective shift on their situation, we will have won.

Do you have plans for future projects after Little Mother Lies? Will they explore similar themes or different ones?

KE: The feature Mother Lies is about the sisters within the richly textured, disappearing community of descendants of Russian exiles in San Francisco. Addiction is just one thread weaving throughout. So we want this film made. I am completing another screenplay set in San Francisco in 1976, based on the true adventures of a rock-concert-crazed teen at the Cow Palace.

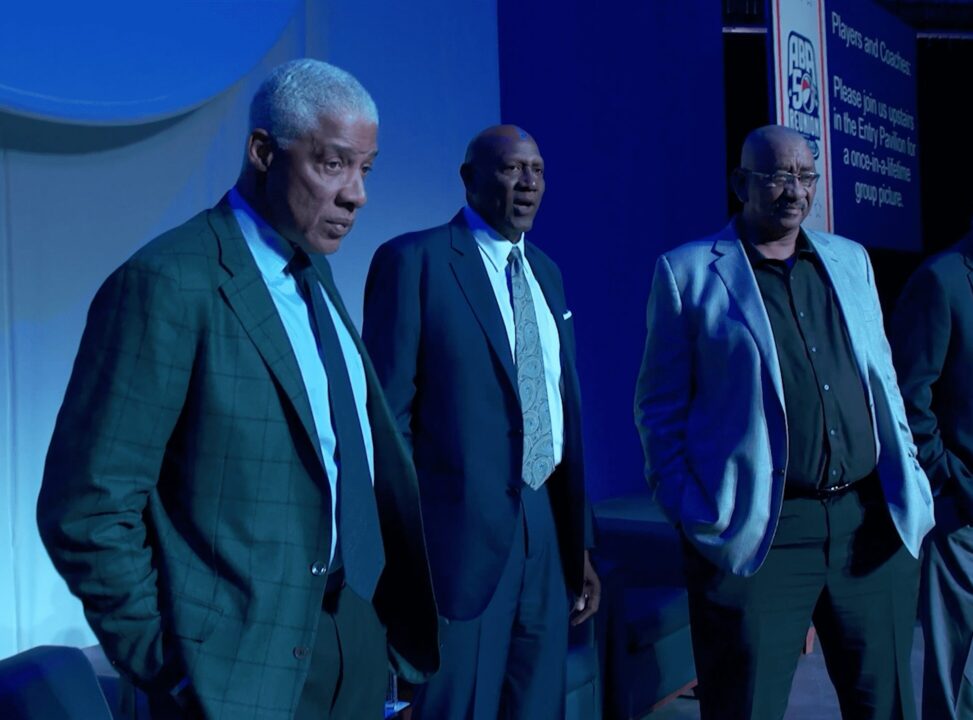

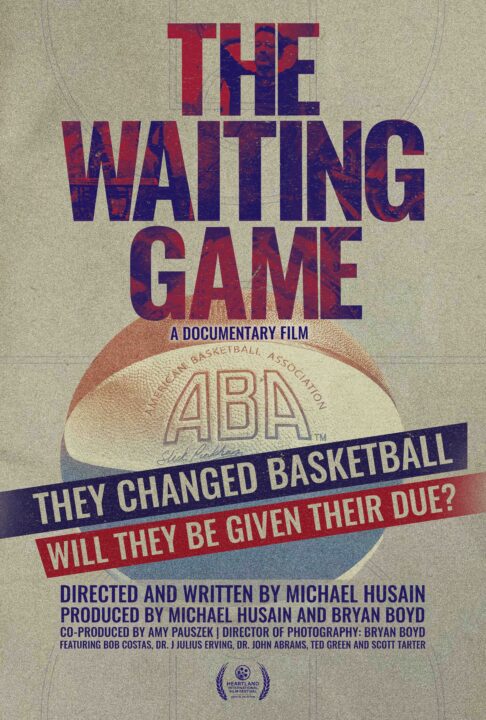

Michael Husain Fights For ABA Basketball Players' Rights

Basketball fans often view the NBA as the sole professional basketball league. However, to do so overlooks the significant contributions of the American Basketball Association that preceded it. The ABA introduced groundbreaking elements such as the three-point line and the slam dunk competition and entertainment features like player fashion, sneakers, halftime shows, and cheerleaders—elements we often take for granted today. The ABA enriched the game and laid the groundwork for the modern NBA, making basketball more enjoyable and dynamic.

READ MORE: ‘The Waiting Game’ Review: The Ongoing Drama Surrounding the ABA/NBA Merger

In the new documentary The Waiting Game, writer-director Michael Husain explores the NBA-ABA merger and former ABA players' ongoing challenges. Featuring insights from legends like "Dr. J" Julius Erving and broadcaster Bob Costas, the film highlights these players' profound impact on transforming basketball into a multi-billion dollar sports and entertainment phenomenon. In our exclusive interview, Husain emphasizes the importance of recognizing the social justice issues surrounding their treatment, ensuring their legacy is understood and appreciated.

What inspired you to create your new documentary, The Waiting Game, about the ABA-NBA merger and the struggles of former ABA players?

Michael Husain: The Waiting Game initially arose from being a sports fan and learning a story I had no idea about. But quickly, it became bigger than sports—about injustice and wrong that must be exposed and corrected.

The guys who played in the old ABA innovated the modern game of basketball, which is now worth billions. How could anyone see them struggling now as older men and not want to help? That was the question that kept coming back to me.

Can you walk us through your research process for this documentary? What challenges did you face in uncovering the ABA's legal history?

MH: There were several key research threads. First, I needed to understand the impact of the ABA on basketball. Terry Pluto’s book Loose Balls is the go-to on that material and other books on the ABA. Next, I needed to understand the deal that went so badly – often called “The Merger” – that it left former players unable to care for themselves in their later years. It happened in 1976, and all those documents were in the possession of Scott Tarter, the lawyer in the film who co-founded The Dropping Dimes Foundation, which was set up to assist struggling ABA players.

Then, I needed to understand the social/cultural impact. The ABA was created in 1967, during the apex of the civil rights movement in America. In some ways, it reflected the changes that were afoot in society. Black cultural influences in the modern NBA are plain to see and celebrated. Much of that came from the ABA, and renowned sports sociologist Dr. Harry Edwards helped me understand it.

You mention the ABA's significant innovations, like the three-point shot and the slam dunk competition. How do you think these contributions are perceived today, especially by newer generations of basketball fans?

MH: I think they are no longer seen as innovations; they are seen as “basketball." That’s the game we all love these days, myself included. So part of the challenge in storytelling was to unfold the story for fans, say, 55 and above, who might recall the ABA, and those under that age who may have no idea it existed.

And, yes, remind them that the ABA innovated many aspects – including entertainment features like player fashion, sneakers, halftime shows, cheerleaders, and more – that we take for granted. The ABA created massive value for the modern NBA and simply made the game a lot more fun.

Who were some of the most impactful people you encountered while making this film?

MH: I appreciated the contributions of legends like Dr. J, Julius Erving, Bob Costas, and others, and they were great interviews. Dr. Harry Edwards, who was active in the civil rights era, invented sports sociology as an academic discipline, is just generally brilliant, and was very impactful in framing the story more widely than basketball.

James Jones and Ralph Simpson, who were extraordinarily gifted as ABA players and now struggle because of how this deal was structured, greatly impacted me. Their strength and honesty in discussing their situations/frustrations hit everyone on the team pretty hard.

Were there any particularly memorable interviews or moments you had while shooting?

MH: Oh yes. We traveled to San Jose State University to interview Dr. Harry Edwards. It was an important shoot for us. We booked a room in their beautiful library, set up for a couple of hours, and were ready to go. Ten minutes before Harry arrives, an announcement comes over an intercom to evacuate immediately. There is an active shooter situation in the building!

We exited to SWAT teams and other law enforcement streaming into the building while I was frantically trying to reach Dr. Edwards to tell him to stay away. We left all our gear in the room. It was very, very stressful. Thankfully, the situation was resolved several hours later, and no one was harmed. We were able to return the next day - all the gear was there and untouched, and Dr. Edwards was a phenomenal interview.

What was the most challenging aspect of bringing this documentary to life, both creatively and logistically?

MH: Our approach involves a very layered story. Therefore, we needed to ensure the audience got enough information and/or emotional impact from each layer we revealed.

While more challenging from a story perspective, I hope the payoff in the last third of the film – which becomes more verité in style as the tiny not-for-profit takes on the Goliath of the NBA – is more rewarding because of the approach.

Why do you believe the story of the ABA's players is important to the history of basketball and sports?

MH: It is important to sports history because the story of the innovations of the ABA is being lost. Having a heart-wrenching set of circumstances allows us to remind people of just how incredible the ABA was. That was very important in why I pursued this.

In what ways do you think this documentary might influence ongoing discussions about athlete rights and corporate responsibility in sports? What do you hope your documentary will achieve regarding advocacy for these individuals?

MH: From a narrow NBA / NBA players union perspective, I hope it reveals to them that some were left out and still need help. It would be a relatively meager sum to the powerful but life-changing to the guys left out or the widows who saw no benefits.

From a broader perspective, I hope it reminds corporate leadership of the terrible consequences when basic humanity isn’t present in the boardroom. Actuaries, accountants, and lawyers are smart and must be informed in decision-making. But if they are not tempered by someone advocating for “golden rule” decency in corporate behavior, what happened to the ABA guys seems to be the result. Real people get hurt.

What message or feeling do you hope audiences take away from The Waiting Game?

MH: I hope they understand these men's immense impact on what has become a multi-billion dollar sports/entertainment juggernaut. Also, the recognition that there is a social justice aspect to how they were treated should not be ignored. Lastly, I hope audiences feel some outrage. As well as a desire to put some pressure on the powers that be to fix a very fixable situation.

Are there any other subjects or issues you’re passionate about that you’re considering for your next documentary?

MH: I’m a big fan of redemption stories. And I’m following a story of a prison re-entry program. In its pilot, it started to empty the lock-up where it was being used. People were getting out of jail and staying out, charting their redemptions. That documentary should be complete in 2025.

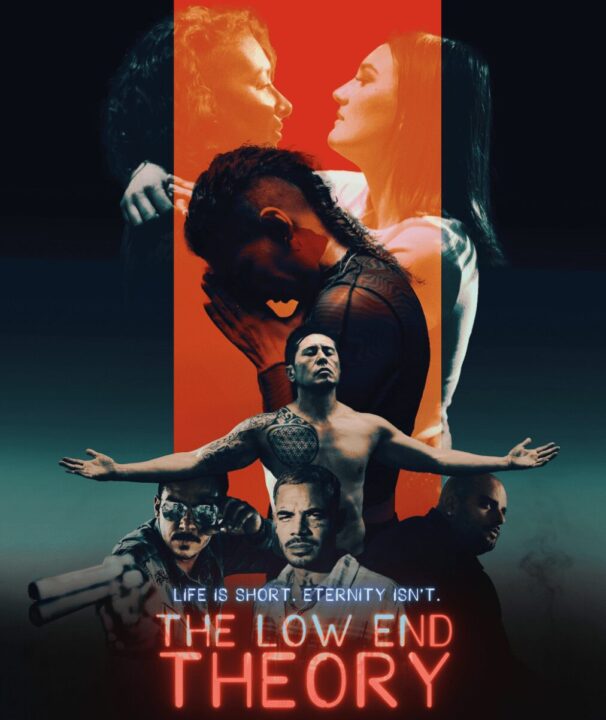

Francisco Ordonez Explores Cosmic Karma Through Film Noir

The karmic relationship we have with the universe interests filmmaker Francisco Ordonez. With his new noir film, The Low End Theory (co-written by the film's lead, Sofia Yepes), Francisco found a way to explore this universal idea through genre filmmaking. "Mainly, I was interested in exploring the question of whether there is such a thing as a cosmic order—whether you call it God or karma. I really wanted to bring the latent mysticism or spirituality of film noir to the surface, to the text level."

READ MORE: ‘The Low End Theory’ Review: A Neo-Noir Set in LA’s Music Scene

In our exclusive interview, Francisco discusses how his Catholic upbringing informed his making movies "about" religion, his film's representation of LGBTQ+ and Latinx voices, and his Scorsese-an style to capture a new type of spiritual film noir.

Cinemacy: It's a pleasure to meet you, Francisco! You've stated that the idea for The Low End Theory came to you when your co-writer, Sofia Yepes, brought you a personal story of hers, told as a film noir. What idea did she initially share with you, and what resonated with you enough to want to make it a feature film?

Francisco Ordonez: I’ll have to leave it to Sofia to decide how much detail she is willing to share, but I can tell you that it was the type of story that just makes you think: Wow. There are some really wild and manipulative people out there! And it’s just baffling what willing participants we can be when we’re in love or think we’re in love.

We can go as far as to put ourselves in physical danger. And we’re capable of violating what we know is right from wrong: our moral codes. And if you throw trauma in there, anything is possible. If you’ve experienced a violation but never received justice, it can really torment you. We’ve all experienced this in small ways. We’ve all experienced situations where someone insults you, and that night, you lie in bed, brooding and fantasizing about what you should have said or done.

In the case of our film, Raquel, the protagonist, has experienced a much deeper violation, one that she never addressed. This combines with this toxic relationship with our film’s femme fatale and results in some extreme noir-level decisions. Sofie mainly wanted to explore toxic love and betrayal. And that’s where I said: “Oh, that’s a noir.” Then we met in the middle, with the themes that she brought to the table on the one hand and the things that interested me on the other.

Cinemacy: What was the collaborative process between you and Sofia – who also stars – in writing the film? Can you talk about what incorporating Latinx and LGBTQ+ characters and ideas about fate and destiny into the story meant to you?

Francisco Ordonez: In terms of the writing, Sofia supplied the pieces of the story and the initial emotions, and I started writing a treatment. I would write and then send it to her. She’d give me notes, and I’d revise them. I did this for about a year. The final treatment that we wrote the script from was about 25 pages, single-spaced. I always write a treatment. I like the freewriting of it. And I like the way it allows me to see the entire film from a birdseye perspective, that is, all the acts and movements. A treatment is almost as good as an outline or post-it beat sheet in this respect.

When I’m writing in screenplay format, I find that I can only “see” the scene before the one I’m working on. And maybe I can see one or two scenes ahead. At least, that’s the way it works for me. Once we got to the script stage, I would send Sofia the script as well as our other producer, Dan Ragussis. I’d get notes and keep revising. As I kept writing, Sofia’s initial ideas morphed into more hyperbolic versions of the original circumstances. It got to the point where the story took on a life of its own and had its own requirements. Like all great actors, Sofia asks great questions about the narrative and the characters. During the writing process, she called me on nuts and bolts logic, as well as emotional logic and motivation.

Mainly, I was interested in exploring the question of whether there is such a thing as a cosmic order—whether you call it God or karma. I really wanted to bring the latent mysticism or spirituality of film noir to the surface, to the text level. People who know my work will recognize the spiritual themes (I guess you can call it “spiritual”) that I often return to. I don’t think anyone would call my films “religious films” or “religious scripts” but instead, films that are about religion.

My theory is that I’m drawn to these themes because I went to a Catholic school starting from kindergarten. I remember being marched into confession after my first communion every Wednesday. I must have been about 7 or 8 years old. At a young age, I was obliged to think about Hell, sin, and salvation. Today, I consider myself a lapsed Catholic, but those themes and questions are hardwired into my brain. I can’t shake them. They’re in there, they’re potent, and they keep coming out in my work. When Sofia and I discovered that our main character had a fixation with karma, that was an a-ha moment for me; that’s when I found my own personal way into this story.

My parents are from Ecuador. Sofia was born in Medellin and moved to New York as a baby. We’re both Latino, so in that sense, it’s only natural that we’d incorporate Latinx characters into the writing even while not necessarily making an effort to make a “Latino film.” Same with LGBTQ+. Sofia identifies as pansexual and while this film has helped her navigate through that journey, we never necessarily set out to make an LGBTQ+ or Latinx film, per se.

Our objective was to take people we are familiar with, put them into a classic genre we love, and show the industry what we, as underrepresented people, can accomplish if given the opportunity. Actors like Robert Deniro and William Hurt solidified their stardom in neo-noirs, Deniro in Taxi Driver and Hurt in Body Heat. Noir anti-heroes are wonderful and challenging roles to play, and Sofia has shown that she can deliver and hold an entire film on her shoulders.

Behind the camera, you have me, a Latino director, a female Latinx producer, and a star in Sofia. Our director of photography (Gemma Doll-Grossman), Production Designer (Marina Pérez Ramirez), and film editor (Miriam Kim) are all women. We had a real presence of women, LGBTQ+, and people of color in front and behind the camera in key positions. That was one of our big goals, and we succeeded. Hiring from underrepresented communities is activism. It sounds like a slogan, but I believe it to be true, and I will continue to live by it.

Cinemacy: What were the first steps you took to begin production after the script was complete? Who were the first key crew members that you brought on?

Francisco Ordonez: Once the script was complete, we started a crowdfunding campaign. We needed seed money to open an LLC, to hire a lawyer to create the LLC, and such. We teamed up with an associate producer, Juan Gil, and a crowdfunding consultant and raised about $25K. The 3 of us, Sofie, Juan, and myself, ran the campaign under the guidance of our consultant, Avenida Productions. (Which are great, by the way.) It was around this time, at the commencement of the fundraising phase, that our Assistant Director, Matt Marder, came on board. He started helping us think about actually making the film, scheduling it, and all of that while we were still tweaking the script.

Once we had a company/LLC formed, then we partnered with actor/executive producer, Ricky Russert and Dan Ragussis and his company Atomic Features. Both Dan and Ricky were instrumental in helping us to raise the private equity and of course, Dan produced the film through his company, Atomic. Sofia and I were blessed to work with them.

Very early on, we brought in actor Rene Rosado. Sofie, Rene, and I have been working together since I was in film school, 19 years now. Both Sofie and I knew that we wanted Rene to play the pivotal role of “Efraim,” Sofie’s best friend in the film. We knew that their real-life chemistry as long-time friends would work great in the film. I think it does.

Also, originally, Rene came in exclusively as an actor, but then he and I formed Shakti Sol Productions along with our third partner, Krishna Tewari. Shakti Sol helped produce and finance the film and consequently, our company has an ”in association” credit. Once we were officially in pre-production, we found our amazing Director of Photography, Gemma Doll-Grossman, her team and production designer, Marina Pérez Ramirez, and her awesome Art Director, Marian Wood.

Cinemacy: How did you find the right actors to embody these complicated characters, and what was your casting process like?

Francisco Ordonez: Working with the legendary casting team of Susan Shopmaker and Matthew Lessall was a blessing. They made incredible suggestions for all the roles or were pivotal in securing actors that I had targeted. For example, I had seen Sidney Flanigan in Never Rarely Sometimes Always and was blown away like everyone else. Same with Ser Anzoategui from the show “Vida.” Ser, like Sidney, was amazing to work with in terms of Ser’s commitment to the role. They’re such a nuanced and intense actor—intense in the best way.

Like Rene Rosado, there were a few actors cast among our friends. For example, Eddie Martinez plays “Uly,” Scotty Tovar plays “Nico,” and rapper and entrepreneur Berner plays “Tino.” They’re friends but they’re also amazing actors that we knew would deliver. It’s really important for me to know that everyone I’m working with is committed to the material, and it’s not just a paycheck. You need that, especially in independent films where paychecks are not necessarily exorbitant. I made sure that everyone we cast had that passion for playing the role and being part of the film.

Cinemacy: Can you describe The Low End Theory's visual style and how it aligns with traditional noir aesthetics while incorporating your unique perspective? Were there any particular films or filmmakers that inspired you?

Francisco Ordonez: For the most part, The Low End Theory doesn’t directly align with a traditional visual noir aesthetic. That was intentional. A lot of classic noir films are rooted in German Expressionism. Given that we filmed in color, I didn’t want to try that style because I felt it would be compromised.

One of the things that I find really fun about neo-noirs, from Chinatown to neo-noirs made today, is that they don’t necessarily have a unifying visual style. They deliver echoes of classic noir via hairstyle or wardrobe (The Last Seduction is a good example of this), but overall, there’s a real eclecticism to the visual aesthetic in neo-noirs. What unifies neo-noirs is the experimentation with the narrative elements of the genre.

With this film, I was looking forward to filtering those narrative elements through my own visual instincts. While I didn’t go for German Expressionism, I was influenced by what I’ll call “Scorsese-an expressionism,” as well as the surrealism of Jacque Audiard’s Un Prophete. Scorsese comes into play via slow motion at certain moments when Raquel is faced with a big decision. We decided that we’d use slow-mo in those pivotal moments combined with tripod shots in what is otherwise a mostly shakey handheld film.

To really pull off Scorsese-an expressionism, you need a preponderance of fluid Steadicam and dolly shots, which I knew we couldn’t pull off based on our schedule. I knew we had to shoot fast, so we opted to shoot 85% of the film with a handheld camera (combined with a lot of available light) and relegate the smoothness of tripod shots to a few well-chosen moments so that those moments really mean something when the audience experiences them.

As far as Un Prophete, our film’s “ghosts” are inspired by Audiard’s film. I love the way that in Un Prophete, the apparition is really an effortless manifestation of guilt versus being explicitly supernatural, you know, a “ghost.” And yet, in Un Prophete, there is nonetheless a kernel of something supernatural about the ghost that I can’t put my finger on. The ambiguity is really nice and resonant for me in that film, so I wanted to play with that in a noir context. This was, for me at least, another way to pull the mysticism of noir up from the subtext to the text.

Cinemacy: The setting can significantly impact a film's tone. How did you choose the locations for this story, and what atmosphere were you aiming to create?

Francisco Ordonez: Independent films have to be very practical about locations. We had to shoot in places we could secure. And yet, we were able to get some great-looking locations. And by “great,” I mean they look visually appealing but also real to the story and the characters. Our production designer, Marina Pérez Ramirez, was instrumental in this via her artistry and vision and by generously devoting untold hours to scout with me. She really helped to ensure that we secured locations that she could make look striking and narratively appropriate.

Another consideration was the fact that I love showing parts of a town that don’t get enough screen time in most movies. For me, that was places like the downtown Los Angeles alley where two characters have a conversation or the bus that Raquel rides to work. We don’t really see the inside of L.A. buses in movies. That was fun shooting in those buses, let’s say, unannounced, even though it was tricky to shoot. Shout out to Sofia and our director of photography, Gemma, who were great sports about getting on those buses and shooting stuff guerrilla.

Cinemacy: How did you secure funding for The Low End Theory, and what advice would you give to other indie filmmakers looking to finance their projects?

Francisco Ordoñez: Three things: First, Tailor your budget to the amount of financing you can raise. Whether you write it yourself or find a script, get behind one that you absolutely adore. You have to be 1000% passionate about any story if you’ll have any chance of success. But do your best to tailor your budget to the financing that you can realistically raise. It’s a tricky thing to decide in advance how much you can raise before you’ve done it. But what’s the point of trying to raise, say, $20 million for your first film when it’s practically impossible to ever get it off the ground?

Nothing, of course, is impossible, but when you’re starting out, there’s so much to learn about the business of raising money, and the more you’re trying to raise, the more you don’t know. It behooves aspiring directors to make their film, to “get on the board,” because there’s just so much to learn about the craft of directing. It’s a mistake to ignore that the outliers are directors with debut films that are masterpieces.

Many think that Scorsese’s first film is Mean Streets, while it was his third. (Or fourth, if you count The Honeymoon Killers, from which he was fired.) Many people think that Tangerine is Sean Baker’s first feature, while it was his fourth. The only way to practice your craft is to make a movie, one you believe in. Therefore, it's absolutely critical to make one, so get behind a doable project, one that you love, and bring it to life.

Second: Don’t try to produce by yourself. Find a producer, one that is as passionate about your project and about becoming a producer as you are in becoming a director. The key is finding partners to help you raise money that are as incentivized to see the film made as you are. Our initial crowdfunding raised $27K. I couldn’t have raised that amount without Sofia and our associate producer, Juan Gil. Same with the equity we raised. My producers and exec producers, several of which were also actors, were pivotal in raising the money. I could not have done it by myself.

Third: Pick one project and throw yourself behind it like an obsessive maniac. There’s a reason why so many people want to make a film but never do. The answer is that it is so damn hard to pull off. Unless you have a trust fund, you won’t do it as an afterthought. You can’t dabble in producing an independent film. It’s just impossible. I found that I had to stop doing everything else other than “work-work,” that is, work to keep the lights on. Once I realized that I had to put down all the side pet projects, music videos, short films, and devote utter focus to The Low End Theory, that’s when things started to move, that’s when money started to move into our account.

Cinemacy: What emotions or questions do you hope audiences take away from the film, and how do you see it resonating with them?

Francisco Ordonez: Our noir hero really struggles with whether it’s right or wrong to do what she does in the name of love. She’s someone who walks around believing that “what comes around goes around,” and she interprets events through that lens. She’s in a transactional relationship with the universe—trying to do good so it comes back to her and avoiding transgression for the same reason.

I think most of us live this way to some degree, even if it’s at a subconscious level, which makes it a universal film. I hope that, however you see Raquel’s ultimate fate, it entertains you and that you think about these questions at least a little about how they relate to your own life.

'Will & Harper' Review: The Road to Rediscovering Yourself

The new documentary Will & Harper is more than a feel-good, hilarious buddy road trip movie. It's also an emotional, heartfelt film about the courage to reinvent yourself amid uncertainties, discomfort, and danger in the face of the unknown. Starring old friends Will Ferrell and Harper Steele, Will & Harper is a film about rediscovery, support, and fearlessly embracing new beginnings through friendship.

Old friends exploring new beginnings

We're all familiar with funnyman Will Ferrell, best known for his starring roles in Achorman and Elf. However, Andrew Steele, an Emmy award-winning former head writer at Saturday Night Live, contributed to his earliest successes. Steele helped Ferrell create some of his most memorable characters during their time on SNL, which resulted in a long-running creative partnership and personal friendship.

Will & Harper opens with Will Farrell sitting for the camera while recounting his decades-long friendship with Andrew while iconic SNL clips play. Will then shares that, years after leaving the show, he received an unexpected email from Andrew: that he was coming out as a trans woman named Harper. Initially stunned, Ferrell reached out to reconnect and explore this new dynamic in their friendship. And so, the pals set out on a road trip across America's heartland to spend time together, gain new perspectives, and help them work through this new and confusing future.

Supporting friends through tough times

From their first reuniting, it's clear how close Will and Harper were then and remain now. Will hops into Harper's four-runner, and the two immediately return to being their old selves, doing bits about Pringle's chips, Walmart, Pabst Blue Ribbon, and more. But as familiar as it is, it's not the same. Even though Harper still loves drinking PBR beer and enjoying shamelessly trashy pop culture, she asks herself, is she still the same person she was before? Will wonders the same; is this a new person before him? What does their new friendship look like?

Will Ferrell is the perfect person for any audience to navigate this new experience with. He provides an endless stream of lightheartedness and laughter to keep the situation fun (asking Harper if she's now a worse driver than before). However, the doc's most memorable moments arise when real life stops the comedy. When Will meets the mayor of Indiana courtside at a Pacers game, Harper shares that he signed anti-trans laws in the state, putting Harper in an uncomfortable position. But the most painful, borderline dangerous moment was during their stop in Texas, where an all-you-can-eat steak challenge turned into a scary affair where locals chastised them, and social media harassed them, leading them to both acknowledge the frightening situation through tear-filled shock.

Embracing new unknowns

At its core, Will & Harper is a movie about embracing the unknown. Seeing Harper and Will confront change despite scary futures is genuinely inspiring. The journey of self-discovery as we age is a theme anyone can relate to. Directed by Josh Greenbaum (Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar), Will & Harper is a terrific documentary that promotes tolerance and should be a must-watch for all audiences. Life can be scary, but it's less so with a little help from our friends.

1h 54m. Will & Harper is rated R for language.

Jonny Caplan Redefines the Gangster Narrative

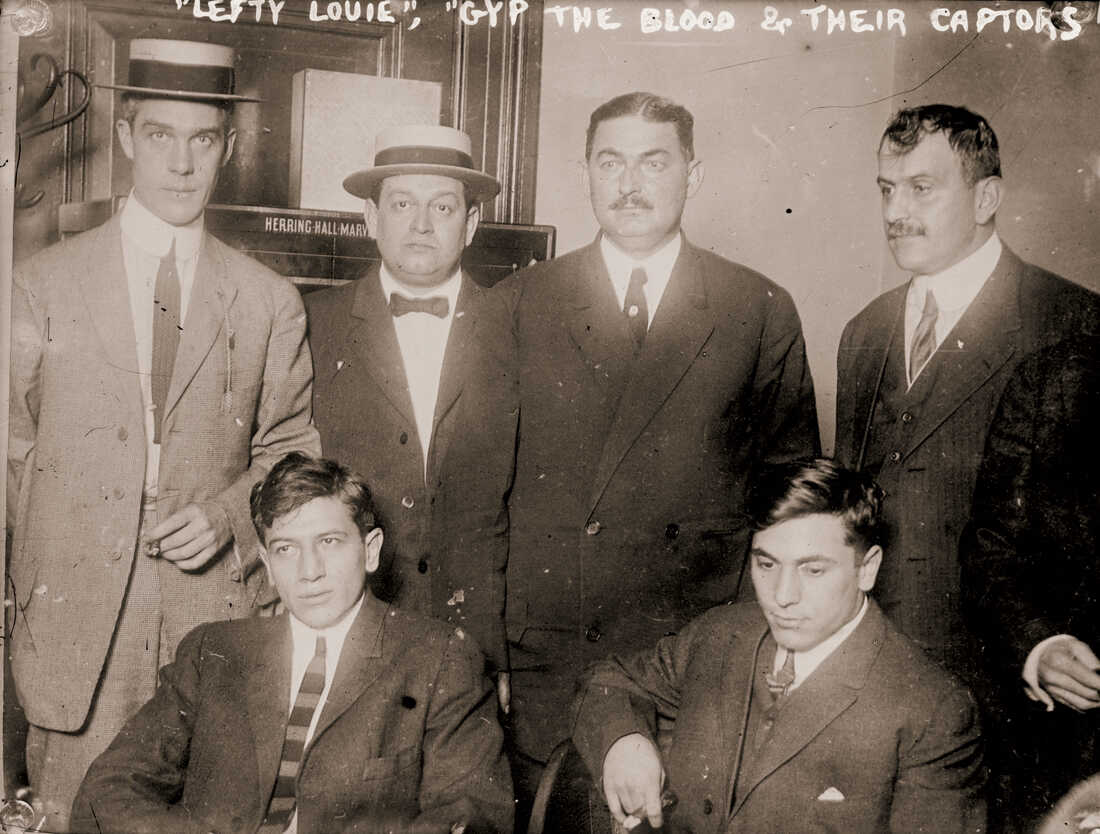

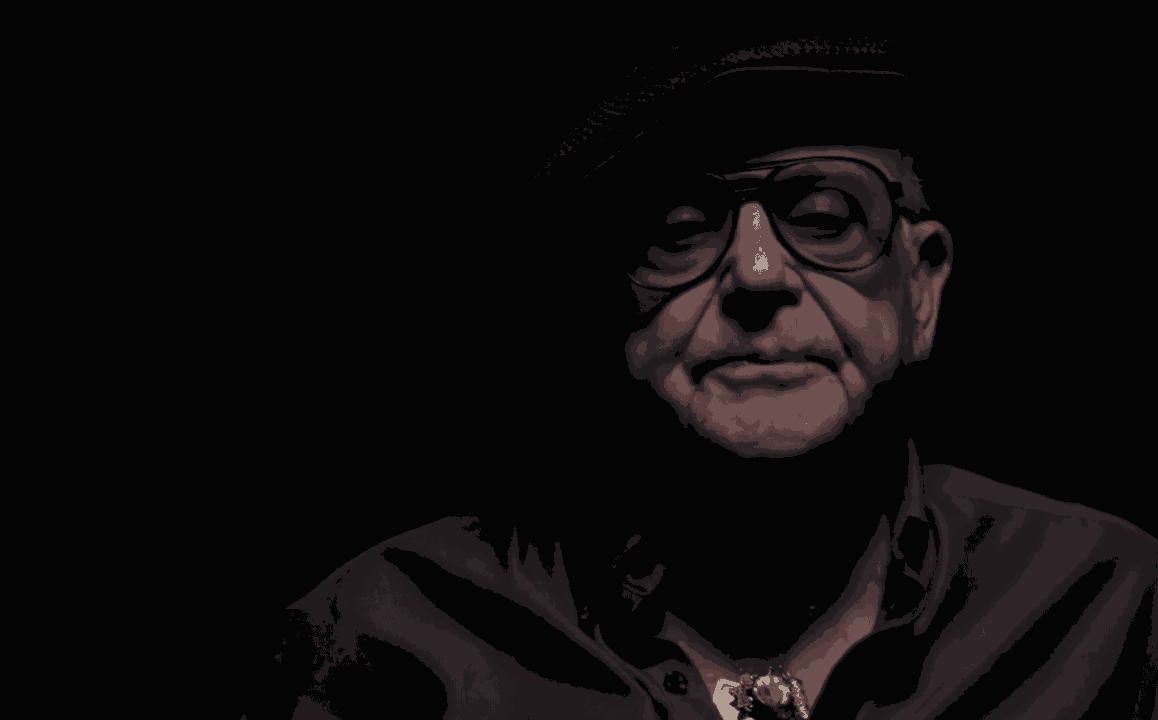

You don't typically hear the term "moralistic gangsters," but Jonny Caplan is a filmmaker dedicated to chronicling one such individual whose life story is too wild to believe. In his new documentary, LAST MAN STANDING: The Chronicles of Myron Sugerman, Caplan interviews Myron Sugerman, a charismatic Jewish American whose life in organized crime challenges the typical gangster stereotype.

LAST MAN STANDING is fascinating because of how Caplan paints an empathetic portrait of the eighty-five-year-old Sugerman. Using archival footage, Caplan illustrates how Sugerman's life of crime emerged in a context where Jewish communities were often excluded from broader societal participation. He shows that Sugerman's involvement in organized crime was driven by necessity and a desire to protect his community. With over fifty hours of interview footage, Jonny Caplan reveals the challenges of getting a tough gangster to share his life story, providing insights into making his documentary and the aspects you might not know.

Cinemacy: What initially drew you to Myron Sugerman's story, and how did you decide to focus your documentary, LAST MAN STANDING: The Chronicles of Myron Sugerman, on it?

Jonny Caplan: Myron's story was highlighted to us by a mutual friend who thought it would interest us. After reading Myron’s book and watching some of his interviews with the Mob Museum and Patrick Bet David of Value Entertainment (which had millions of views), we immediately loved the unique and iconic angle of Myron’s story and a side of the American Mob which isn't usually told, of the charming, humorous and ‘moralistic’ gangsters, having to do what they needed to do to protect their communities.

Myron is a one-of-a-kind individual who, at the ripe age of 85, still has immense passion and vigor and manages to take up all the air in any given room. Myron's story is utterly iconic, and we immediately agreed on a deal to acquire the life rights to his story so that we could initially cover it in the factual feature doc, which additional scripted dramas will follow.

Myron Sugerman's life spans multiple significant historical periods and events. How did you approach structuring the documentary to balance these elements while maintaining a coherent narrative?

Jonny Caplan: We initially filmed over 50 hours of interviews with Myron discussing his life story and the many twists and turns of his covert missions across 80 countries around the world; however, it was crucial to have a coherent storyline and a straightforward, definitive narrative of Myron family upbringing and experiences without going too much into detail in any of the twists and turns.

Part of building the feature documentary was structuring Myron's life in a 90-minute storyboard that clearly outlines how vast his endeavors were and allows for details of each of the extensions to this in our upcoming scripted productions.

Given Myron Sugerman's complex background involving Jewish and Italian mobs, how did you navigate the potential challenges of portraying these aspects authentically and sensitively?

Jonny Caplan: Myron's life story is the real deal, a firsthand account from a second-generation gangster who experienced it all himself and is still here to tell the tale; this makes his story unique and authentic. Most know the story of the Italian Mob, but others do not know the story of the Jewish Mob and the tight allegiance between these two underground parties.

They worked together to ensure succinct and synergistic business and assisted each other with domestic and social issues. For research and diligence, we visited many of Myron's family, colleagues and associates, scholars, legal experts, and journalists.

The documentary explores Sugerman's role in combating antisemitism. Can you discuss how you highlighted this aspect of his life and why it’s particularly relevant today?

Jonny Caplan: As with many of our cutting-edge documentaries, our timing happens to be impeccable, and in the case of Myron‘s story, we happened to tell the story at a time when anti-Semitism is as rife on the streets of the US as it’s ever been including in the 1930s when there were Nazi rallies and pogroms on the streets of New York and New Jersey.

Unfortunately, the antisemitism problem has been spiraling out of control, which is why it’s so important to understand the root of this problem and what some of the tough Jews did back in the day to thwart it.

What was the most surprising or unexpected revelation you encountered while researching Myron Sugerman’s life and work?

Jonny Caplan: Myron has incredible energy, panache, and charisma. He also has unsuspecting morals, which may not have been expected from a gangster. As Myron puts it, they weren’t gangsters; they were just opportunist entrepreneurs and pioneers carrying out business activities that were prohibited at the time but are regulated and approved today.

Remember, many of the Jewish mobs had become outlaws because they were banned due to their race from having other professions at the time.

How did you approach interviewing Myron Sugerman and other key figures involved in the story?

Jonny Caplan: When the documentary was slated to begin filming, Myron was hit with two bouts of Covid 13 and pneumonia in the week leading up to filming. We thought that this 83-year-old man at the time would be down and out for the count, and we would have to postpone filming if we ever made it happen. Several days later, I got a phone call from Myron telling me that I had better not change any of the arrangements and that he was preparing to film.

Unfortunately, restrictions prevented me from crossing the Atlantic and boarding a plane to sit with Myron throughout the filming. Hence, we had to use a minimal Covid-safe film crew who set up remote directing for me with huge monitors and AI robots. I had to interview Myron remotely from the UK, and I only met him personally several weeks after we completed filming.

Indie films often involve a hands-on approach from directors. Can you share some insights into the specific roles you took on yourself during production, from shooting to editing?

Jonny Caplan: I always try to take a hands-on approach to our productions; I find that in the creative process, if the director themselves isn’t explicitly involved in every element of it, then they cannot possibly understand what is required and provide the production team with direction and clarity on what needs to be done.

Like a showrunner, I am involved with all production elements, including design, storyboarding, casting, logistics, sound, lighting, cameras, Call editing, and more.

Were there any challenges or memorable moments from these interviews?

Jonny Caplan: Oh, yes. Often, interviewing a tough gangster is not the most straightforward feat as he doesn’t like to listen to instructions, doesn’t understand the production process, and just really wants to tell his story.

So often, getting Myron into the basement wearing what we would require and asking him to sit under the spotlight in a particular manner would receive a response like “Jonny, cut the bullcrap, turn on the cameras, and record, I'm ready to talk.”

The documentary follows Sugerman's best-selling book. How did you integrate elements of the book into the film, and did you make any significant changes or additions to enhance the narrative?

Jonny Caplan: The book has a vast narrative about many aspects of Myrons' life. With only 90 minutes to tell the story, we had to build one clear path through his life, which reads differently from the book but is complementary in every way.

What impact do you hope the documentary will have on viewers, particularly regarding their understanding of antisemitism and the Jewish mob’s role in American history?

Jonny Caplan: From what I’ve been able to understand, the Jewish Mob was made up of tough Jewish family guys who were middle-class and unable to get the sort of jobs and the lives they wanted and had to resort to a little bit risky professions. There was also burgeoning antisemitism from the nazi bund. They had to take a chance to do things that weren’t strictly legal to save their families and communities.

I believe the Jewish Mob is largely unknown, and the minutemen who stood up to the Nazis on the streets of the US. Meyer Lansky and Benjamin “Bugsy Siegel,” for instance. They were pioneers of Las Vegas as we know it and the gambling and resort phenomena that have taken the world by storm. Jewish gangsters werent just tough, they were also smart, pioneering and well intended.

Karim Shaaban Slows Down to Stay Present

The film industry can be a demanding place to work. Nobody knows this better than Karim Shaaban, a filmmaker who took stock of his life when he could not be present for the passing of a family member due to his commitment to being on a film set. Karim grapples with themes of responsibility, loss, and emotional detachment in our fast-paced world in his poignant new short film, I Don't Care if the World Collapses Collapses.

"I hope it prompts viewers to reflect on how the pace of life can lead us to sacrifice what’s truly important and real and to recognize the need to stay aware and connected to ourselves along the way," he wisely states. In our exclusive interview, Shaaban reflects on the creative journey of making his film, the challenges of indie filmmaking, and how this project has reshaped his life and career.

It’s nice to meet you, Karim! You’ve mentioned that you were inspired to create your new short film, I Don’t Care if the World Collapses, after harrowing experiences over your on-set dealing with similar circumstances of prioritizing health. Given its personal and intense nature, can you elaborate on your emotional journey while developing this short film?

Karim Shaaban: It’s a pleasure to talk with you, Ryan. The emotional journey behind creating I Don’t Care if the World Collapses was intense. Initially, I questioned whether pursuing this story was the right decision, especially at this career stage. At that time, I was already deep in prep for another project, which eventually got canceled in 2023. Once I decided to dive fully into this film, everything started to fall into place, almost like a dream.

From the first call, everyone I contacted was enthusiastic and eager to participate. There was this shared excitement and mutual respect, and everything seemed to move seamlessly. After completing the film and having screened it twice, I realize this project has become a turning point in my life and career.

I’ve gone on a reflective journey through making and sharing this film. It’s made me look closer at myself—what kind of stories I want to tell and what draws me to filmmaking. In many ways, this project felt like a mirror, opening me up to deeper connections and trust, both personally and creatively.

Can you discuss the main themes you wanted to explore in this film?

Karim Shaaban: The main themes I wanted to explore in this film are responsibility, loss, and the emotional detachment we all develop because of how our lives are structured. I wanted to examine the modern human being—someone willing to push their emotions aside and keep moving forward, creating products and achievements that ultimately feel meaningless. It’s about feeding into a machine that doesn’t care about the person behind it.

Instead of just observing this disconnect, the film places the audience directly in that experience—forcing them to confront the emotional void we create when we prioritize this endless cycle of productivity over genuine human connection. It’s not about showing what happens but rather making the viewer feel the weight of that choice.

Your statement critiques the capitalistic world and its detachment from personal realities. How did you integrate this critique into the film’s dialogue, characters, and plot?

Karim Shaaban: This critique is embedded in how the story is portrayed and how it shifts the narrative around these moments. Often, these situations are celebrated as signs of dedication, commitment, and professionalism—where people are proud of pushing their emotional and mental state aside to give work all the power and space it demands. But through this film, I wanted to challenge that perception.

As for the dialogue, characters, and plot, I think Wael Hamdy, who worked closely on those aspects, can speak more deeply about it. From my perspective, though, the characters themselves are reflections of this critique. Take Magdy, the production manager in the film, who says he’s holding onto his position with all his strength, unable to risk it for anyone or anything. This mirrors how so many people navigate our modern world—working tirelessly to stay in place, willing to sacrifice more and more to keep moving forward. But often, the small sacrifices we make, the ones we don’t even notice, can grow over time and ultimately reshape who we are. That’s the unsettling reality I wanted to capture.

How did you approach directing the scene where Farouk receives the disturbing phone call? What was your vision for this pivotal moment?

Karim Shaaban: For that scene where Farouk receives the disturbing phone call, my vision was to create a sense of harmony first—a moment where everything feels calm and flowing. I wanted the director on set to be happy, guiding the young girl and the actor to enjoy the moment fully. Then, with the unexpected call, that harmony shatters. I wanted to capture that shift gradually, showing the whole set as the mood changes, focusing on the eye contact between the crew as they silently ask, What’s happening? What do we do now?

But honestly, watching Emad Rashad perform this scene on set was breathtaking. We were all in awe of his presence—this legend truly delivered. At first, I was stunned, and even though I felt I should adjust something and reshoot, I hesitated to ask him to do it again. It felt like a perfect moment, and part of me was embarrassed to disrupt that. After consulting with Beshoy Rosefelt, our DoP, he encouraged me to ask Emad and let him decide. To my relief, Emad agreed, and he performed it precisely as he had the first time—just as powerful. In the end, I couldn’t resist using the first take when it came to editing. It felt so natural in the moment, and I knew it captured the raw emotion we all felt on set.

What was your process for casting the roles of Loubna and Farouk? How did you find actors who could convey the urgency and emotional stakes of the story?

Karim Shaaban: For Loubna, I had been following Salma Abu Deif’s work for quite some time, admiring her growth as an actress. Her development was impressive, and I always knew I wanted to work with her someday. In 2023, she starred in the Ramadan series Al Imam, and there was a particular scene where she was alone, navigating a complex emotional moment. I paused at that scene because her performance was so raw and genuine—wholly unfiltered and natural. At that moment, I knew Salma was the perfect choice for Loubna. Even if it didn’t work out for this short, I wanted to collaborate with her on another project.

For Emad Rashad, who plays Farouk, he came highly recommended by Wael Hamdy. Emad is a legend in his own right, primarily known for his work in the 80s and 90s, and with his theatrical background, he’s truly a master of the craft. When we first met, he told me the story reminded him of his best friend, the legendary Farouk El Fishawy, who had passed away. That personal connection made his portrayal of Farouk even more powerful, adding an emotional depth that brought the role to life.

Were any scenes or elements of the film that were particularly challenging to shoot or edit? How did you overcome these challenges?

Karim Shaaban: The whole film challenged me because I only had the budget for three shooting days, which I funded entirely from my savings. There was no extra money for additional hours, so part of me was terrified that we might not finish everything in time. I vividly remember the first shooting day—we spent around seven hours on a single scene. It was a deceptively complex scene because, while it was technically one scene, the blocking and movement made it feel like we were shooting three different ones. That day, I seriously doubted whether we could complete everything as planned.

But somehow, we made it work. I had to trust the process, enjoy it, and let things flow naturally. Ultimately, everything came together even better than I could have hoped. It was about letting go of the pressure and allowing the film to take its shape.

How did the constraints of an indie budget influence the production decisions and overall approach to making this film?

Karim Shaaban: I didn’t approach this project with the typical indie film production mindset or market in mind. I had complete freedom in decision-making and never viewed the project with any hard limits or budget caps. I focused on bringing my vision and story to life and wanted to craft every detail with dedication and love.

Of course, I had a budget in mind, and we did our best to stick to it, but in the end, we exceeded what we planned. Whenever something unexpected required more resources, I was ready to invest further. I poured a year’s worth of commercial work into this project, which brought me happiness and freedom. My goal was always to serve the story, and by the end, I felt there was nothing more I could’ve done—it was all on the screen.

How does your experience with this short film reflect the broader challenges and opportunities in the indie film industry, and what advice would you give aspiring indie filmmakers?

Karim Shaaban: My experience with this short film led to profound realizations about myself and the industry. As filmmakers, we often push ourselves by this need to impress, to show the world how exceptional we are—constantly seeking new ideas, fresh visuals, and ways to stand out. While that pursuit is noble and worth chasing, the process becomes more personal. I’ve come to see that art is really about the self. It’s a medium for communication and connection. We’re meant to be present in what we create, allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and creating spaces for dialogue, growth, and reflection. It’s about learning more about ourselves and each other and building towards a more peaceful future.

For aspiring indie filmmakers, my advice is simple: be yourselves. Don’t be afraid to lean into stereotypes or preconceived notions; open your hearts and create with love and enjoyment. That’s where originality truly comes from. I’m curious about you, your story, and how you bring it to life because it comes from a place you can access. The idea and execution reflect who you are, so stay present and entirely exist within the process. That’s where the magic happens.

What do you hope audiences take away from this short film, especially regarding the characters’ experiences and the overall narrative?

Karim Shaaban: I see this short film as part of a more extensive dialogue—actually, I think all films are. They’re like condensed conversations crafted with intention and purpose, where we spend months or even years preparing our side of the discussion. Then, the audience’s side of the conversation begins when the film ends. That’s what I’m hoping for with this film.

I want it to lead to serious discussions about right and wrong and how to ensure our emotional and mental well-being throughout life. I hope it prompts viewers to reflect on how the pace of life can push us into sacrificing what’s fundamental and recognize the need to stay aware and connected to ourselves along the way.