'Secret Mall Apartment' Review: The Power of Art and Rebellion

Secret Mall Apartment tells the stranger-than-fiction true story of a group of friends who lived in a hidden space inside a mall for four years—completely undetected. Blending intimate interviews and self-shot archival footage, this wildly entertaining and poignant documentary depicts an act of rebellious artistry in an era of consumerism that will make you appreciate the fleeting nature of life.

The film opens with humorous news segments that show how, in 2003, eight young Rhode Islanders built a secret apartment inside the newly opened Providence Place Mall, where they lived undetected for four years. However, they weren’t just rebellious squatters—they were RISD students and artists, part of a thriving underground scene.

Before this, we learn that this quirky artistic bunch, led by the group’s eccentric and visionary leader Michael Townsend, was displaced, losing their creative and living spaces to redevelopment. Their mall apartment was more than a shelter; it was a statement—an artistic rebellion against capitalism’s grip on public space.

And so, they smuggled in furniture, ran electricity, and installed a locked door that only they had the key to. What began as an experiment in survival became a meditation on public versus private space, consumer culture, and the audacity of turning a corporate mall into a personal sanctuary.

Director Jeremy Workman (who also produced and edited the film) tells this bizarre and brilliant story with a creative and sharp eye. The film’s unconventional style blends sit-down interviews with low-res, old point-and-shoot video footage that the friends all shot, plus re-creations that immerse the audience in the era. The very existence of this footage is incredible, making the documentary feel like a time capsule of an impossible moment.

Secret Mall Apartment also shows how the group’s creativity extended into the world. They pioneered large-scale tape art installations, decorating Hasbro Children’s Hospital with intricate murals. After 9/11, they brought public art to New York, offering a moment of beauty amid devastation. These projects reinforce the film’s themes—art as resistance, as expression, and as a way to make the impermanent feel permanent, if only briefly.

While Secret Mall Apartment is a fascinating and well-crafted portrait, one lingering question remains: beyond celebrating these artists, what does it truly reveal about them? The film touches on Michael’s struggles, including the unraveling of his marriage, but doesn’t fully explore the long-term consequences of their lifestyle, or what they may have been running from.

Ultimately, Secret Mall Apartment holds a secret of its own. Beneath its humor and spectacle lies a meditation on impermanence—on lives hidden in plain sight and on a world that, much like the apartment itself, was never meant to last.

Alex Kaplan Reflects on Childhood and Healing

What happens when a teddy bear costume becomes the starting point for a profound exploration of adulthood, childhood, and self-discovery? In this exclusive interview, filmmaker Alex Kaplan opens up about the creative journey behind Safe, a short film that started with a playful idea but quickly evolved into something much more profound. Alex reveals how the film's narrative and tone took shape through his collaboration with co-writer and actor Caleb and his quest to reconnect with a lost sense of play. It’s a thought-provoking look at how something as simple as a teddy bear can uncover raw vulnerability and the complexities of being human.

Beyond Safe, Alex also shares his vision for Of Substance, the distribution company he founded to turn short films into tools for mental health healing. Through this initiative, films like Safe are helping to foster conversations around mental health, trauma, and self-acceptance in therapeutic settings. This interview delves into how Alex’s unique approach to filmmaking and distribution is making a real-world impact, and how he hopes to continue shaping the future of short film as a catalyst for social change.

Cinemacy: Great to meet you, Alex! I hear Safe started with a teddy bear costume. How did that idea become a film exploring adulthood, childhood, and self-discovery?

Alex Kaplan: Hey Ryan! Thanks for having me. And HA! Oh boy, that teddy bear costume…

Caleb and I had already been talking about exploring the sheer weight and overwhelm of just being a person today. We both struggle with ADHD, so we instantly bonded over how chaotically our minds work and knew we wanted to capture that—but in a way that felt playful and unexpected.

At the same time, my wife had recently challenged me to reconnect with my childlike sense of play, something I’d totally lost touch with. Safe to say, I’ve been taking life way too seriously these days.

So when Michael, during a creative meeting, slyly mentioned, “I do have a teddy bear costume,” something just clicked. The contrast of a grown man, worn down by life, confiding in his childhood teddy bear was so simple, honest, and correct. I pitched it to the guys, and they immediately said, “Yep. That’s it. Let’s do it!”

Cinemacy: You mentioned the concept for Safe came together quickly with Caleb, your co-writer and lead actor. How did your collaboration shape the film’s tone and direction?

Alex Kaplan: Caleb is unlike anyone I’ve ever met. He calls everyone “Human”—as in, “What’s up, human?”—which is just so perfectly him. Actually, even though you never hear or see his name, Caleb insisted that his character be named Hugh—for human. I love that!

He’s deeply compassionate, naturally vulnerable, and embodies the idea that we’re all in this together.

So the juxtaposition of his childlike warmth against his long hair and grizzly beard made this film an absolute breeze—it was obvious what we needed to do. His ability to talk so freely about things we all struggle with but rarely admit out loud shaped the film's entire tone. He doesn’t just act vulnerable—he is vulnerable, and that makes everything feel effortless.

We never had to force anything; we just let it be what it wanted to be—and that’s what made the collaboration so fluid, easy, and fun.

Cinemacy: How did you decide on the visual style and tone for Safe? What choices did you make to evoke nostalgia and the magic of childhood?

Alex Kaplan: We only had a teddy bear at first, but on set, the film became much bigger than I’d imagined. I initially saw it as a simple, grounded moment—Caleb beside his teddy bear, revealing that he’d imagined it as larger than life. Then Michael said, “Let’s shoot through the peephole.” Suddenly, the bear wasn’t just imagined—it had a home of its own.

That took the film from a metaphor to a magical little world. Then Sarah sealed the nostalgia, suggesting 4:3 framing to mirror the peephole, making it feel like a frozen childhood memory. Her color work gave it that soft, faded, dreamlike feel.

None of these choices were planned to evoke nostalgia—we just trusted the story, and it naturally found its way there.

Cinemacy: What did you learn about yourself while making Safe, both as a filmmaker and personally, given its deeply personal themes?

Alex Kaplan: To tell the truth, I don’t think of myself as a great filmmaker—that’s not my focus. My focus is impact. I love taking half-baked ideas that might help others and collaborating with talented people to bring them to life.

That said, I learned I can make my film style in 60 seconds. But I’d rather not. (laughs) One minute is so short—you barely get into something before it’s over. We pulled it off, but I prefer letting stories breathe a little more.

Personally, Safe reminded me I still have it in me. I hadn’t directed my own piece since before COVID-19, and honestly, I wasn’t sure if I could do it without my longtime creative partner, Brian. But this film showed me I bring something real to the table, no matter who I work with.

I mean, it helps that the people I worked with were wildly talented and supportive. (laughs)

Cinemacy: The core message of Safe is about rediscovering childhood magic and unconditional love. How do you hope viewers will respond to this, and what do you want them to take away?

Alex Kaplan: I hope Safe triggers a memory—that one special thing from childhood.

Maybe it’s a teddy bear, a blanket, a hiding spot, or a person who made them feel safe. Whatever it is, I want this film to spark that thought and make them pause.

More than that, I hope it permits people to reconnect with that part of themselves. Life gets heavy, but we all have moments from our past that remind us of who we were before the world got too loud. If Safe helps someone tap back into that—even for a second—then we did something right.

Cinemacy: With Slamdance’s 6XTY category’s one-minute limit, how did you distill your message so quickly? What challenges did you face in the short timeframe, from writing to filming in just an hour?

Alex Kaplan: Constraints can be liberating. When you only have an hour to shoot, you can’t overthink—you just have to trust the process and commit to the moment.

And we didn’t ask, How do we shrink this story to 60 seconds? We asked, What kind of story fits within 60 seconds? It had to be one focused emotion, monologue, and surprising reveal—anything more would’ve been too much.

Still, Caleb practiced that monologue like his life depended on it, delivering it at lightning speed while making every moment count. And a huge shoutout to our editor, Umar Malik, who worked magic to cut lines and restructure it without losing a single ounce of impact. Even I couldn’t tell what was missing after his cuts!

Cinemacy: Safe will premiere at the 2025 Slamdance Film Festival. What does this milestone mean to you, and what are you most excited about for the premiere?

Alex Kaplan: This is the first film I’ve written and directed that I’ve ever submitted to a festival.

I’ve made over a dozen films for Of Substance that are actively used in treatment, but I never played the festival game. It takes time, money, and effort, and since I wasn’t trying to break into the industry, it never felt like the right move.

But I also knew visibility and recognition matter. Having a film at Slamdance is a massive milestone—for me, for Of Substance, and for our work. It validates that we can tell powerful, gripping stories WHILE using them as tools for healing in treatment.

We’re simply over the moon about it.

Cinemacy: As the founder of Of Substance, a distribution company turning short films into tools for transformation, how has your approach to distribution evolved, and how do you see short films like Safe driving social change?

Alex Kaplan: There’s just so much noise out there—so much content, so many platforms, all fighting for attention. We realized early on that we didn’t want to compete in that space. Instead, we created our lane—turning short films into utilitarian tools used by mental health professionals in therapy, treatment centers, prisons, schools, and beyond.

And now, Of Substance is an award-winning organization providing short films—comedies to thrillers touching on mental health, addiction, trauma, and shame—to mental health professionals to enhance therapy, spark introspection, and accelerate healing.

Instead of chasing festival runs or streaming deals, our films go where they can make a direct impact. And that’s where Safe belongs, too—in places where it can help people process emotions, open up, and heal.

Cinemacy: What role do you envision Of Substance playing in the future of short film distribution and sparking conversations or action in society?

Alex Kaplan: We’re working to get our platform into the hands of treatment professionals worldwide, normalizing the value of Cinema Therapy—using movies as a tool for healing and growth, eventually getting insurance to cover them as an Evidence-Based Practice, which has never been done.

And–Big news for short filmmakers–We’re starting to invite other short films to join our platform!

There are incredible short films out there with nowhere to go, so we built a place for them!! We want Of Substance to be the home for impactful short films—where they don’t just sit in a digital graveyard but actively help people in therapy, education, and beyond.

So if you have or know of a film that would be a great fit, PLEASE reach out through our website—ofsubstance.org.

But beyond that, we want to bring this approach into the mainstream—especially in a time of such intense cultural division. Films can bring people together, help us hear one another, and develop empathy for those we see as different from ourselves.

There’s so much untapped potential in using film as a tool for transformation, and we’re committed to leading that charge.

Cinemacy: What advice would you give fellow filmmakers looking to make short films or work under tight deadlines and constraints?

Alex Kaplan: We launched Of Substance by making eight films in eight months—because we knew that if we got stuck trying to make each one perfect, we’d never get anything done.

You’ll never get it right—but that’s not the point. The point is to make it, learn, and make the next one better.

So trust yourself. Be bold. And just make the damn thing.

For more about Alex Kaplan, 'Safe' and Of Substance, visit https://www.alexkaplanfilms.com/ and https://www.ofsubstance.org/

Jessica Perlman Bridges Worlds Between the Deaf and Hearing

Being a CODA (Child of Deaf Adults) herself, filmmaker Jessica Perlman knows the challenges of navigating between the Deaf and hearing worlds. In her new short film, Talk, Perlman offers an intimate and thought-provoking exploration of the complex nature of communication, especially for those constantly translating between two worlds. Vividly portraying how even the most straightforward situations can be layered with meaning and miscommunication, Talk will resonate deeply with everyone seeking it out.

In our exclusive interview, Perlman opens up about her personal experiences and how they influenced her creative process, bringing a unique perspective to filmmaking. As the film's writer and director, Perlman, shares, "For a Deaf audience, I hope the film makes them feel seen, their lives centered, and even find humor in the relatability of difficult situations like this."

Cinemacy: It’s a pleasure to meet you, Jessica! I’d love to hear more about what inspired you to create your new short film, Talk.

Jessica Perlman: One of the hardest things for me to explain about being a CODA, is the management of all the conversations happening at once and how they funnel through you. So I decided to show it! By putting the audience within the layers of words, meanings, and contexts– I believe it gets across how difficult it is to manage, yet still hold your place in all of it.

Cinemacy: The film’s premise involves a seemingly mundane issue—a broken air conditioner—but it evolves into much more. How did you decide to use this particular scenario as the foundation for the tension in the story?

Jessica Perlman: This scenario came from wanting to use the line about D. R. Horton. It was an experience I had when I was translating for my stepdad about his home, and I thought he signed “Doctor” Horton instead of the name of the home manufacturer. One of those embarrassing moments you can't forget, but that’s how I learned what D. R. Horton is!

Cinemacy: Talk explores the breakdown in communication through the lens of a Deaf man and his translator. As the film’s writer, can you talk about the challenges you faced in conveying this complex story visually, without relying heavily on dialogue?

Jessica Perlman: That was the fun part for me! I chose to frame up the Deaf character in ways that felt confined, pressed up against, and stifled. A few shots even frame out his hands. A fluent speaker can still understand what he’s signing, but he’s cut off from communicating with the repairman. That also meant performances were key in capturing the frustration seeping through so that you didn’t need to understand the words to understand the character.

Cinemacy: Talk focuses on the challenges CODAs often face when navigating between the Deaf and hearing worlds. Can you discuss how these experiences shaped your perspective as a filmmaker and storyteller?

Jessica Perlman: As a CODA, I have a unique point of view in my storytelling. Being able to hear and sign placed me directly in the middle of two different worlds, often having to translate between the two. So this translator role I grew up with was one of my biggest draws to directing. A director has to translate from page to screen, and from their vision to their collaborators. Additionally, the nature of ASL is not just visual but performance-based. I think this has allowed me to identify and craft great performances. With every story I tell, I harness these inherent skills and the desire to center stories from unexpected places.

Cinemacy: As a director, what did you learn during the making of Talk that surprised you or challenged your expectations?

Jessica Perlman: My experience making Talk was quite extraordinary. This was the first time I could work with Deaf talent, and I couldn’t believe how quickly Jacob and I adapted. We came up with our signs for film-specific words. I was directing the performance from behind the monitor while signing at the same time. It felt like speaking my native language on set for the first time. Something I never thought could be possible. It opened my mind to what could be accomplished in this dynamic.

Cinemacy: What is the one key message or feeling you hope audiences walk away with after watching Talk?

Jessica Perlman: I hope this film will engage hearing audiences in a conversation without their usual tools– putting together the clues to understand not only the words but the characters' individual experiences. For a Deaf audience, I hope the film makes them feel seen, their lives centered, and even find humor in the relatability of difficult situations like this.

Additionally, for all the CODA’s out there, this film is from our point of view. We are often involuntary witnesses to discrimination and prejudice at young ages, which can form a strong impact leaving them to deal with uncomfortable situations on their own. Even though we have a quick moment with our characters, I believe this short film will make a lasting impact on audiences of all types.

Cinemacy: Finally, do you have any future projects planned or dream goals?

Jessica Perlman: I’ve developed a feature based on the short film that would be a dream to shoot. I also have a couple of other shorts I’ve written and developed that I’m looking to shoot this coming year; specifically one about language acquisition in Deaf children.

For more about Jessica Perlman and 'Talk,' visit https://www.jessicalperlman.com/talk-short-film

Carolina Perelman Embraces Truth Without Shame

Not many directors would weave reality and fiction together in their feature debut, let alone do so by exploring deeply personal secrets through a "docu-fiction" lens. But Carolina Perelman did just that with Confesiones Chin Chin. The film, which will have its world premiere at the 2025 Slamdance Film Festival, delves into the blurred lines between truth and persona, capturing the raw, unfiltered nature of human emotion and vulnerability.

In our exclusive interview, Perelman shares the inspiration behind the film’s unique approach, how jazz shaped its chaotic energy, and the balance between humor and serious topics like trauma and fidelity. What does she hope audiences take away? A reminder that honesty can bring freedom and connection, allowing us to embrace our truths without shame.

Cinemacy: It’s a pleasure to meet you, Carolina! You describe your feature film, Confesiones Chin Chin, as a "docu-fiction" that draws from real secrets and confessions. Where did the idea to intertwine the line between reality and fiction come from, and how did you balance these elements during the writing and filming process?

Carolina Perelman: It’s a pleasure to meet you too! The idea of intertwining reality and fiction in Confesiones Chin Chin emerged from a fascination with how these elements already blur our everyday lives. It’s impossible to reveal the rawest truth because sometimes we don’t even know it. I think deeply personal or uncomfortable questions, especially about society's morality, values, family, and friends, often force us to pretend who we are. That’s why… by the way, I love “Be Yourself” by Frank Ocean because he says, “Be yourself and know that that’s good enough.” It’s difficult to understand that, and that is why I wanted to explore that tension, that line between reality and fiction in this film.

My main inspiration for this film was Jason Holliday in Shirley Clarke’s film, Portrait of Jason, where the lines between the character—Jason Holliday—and the person blur as layers of a persona are peeled back. We similarly embraced the absurdity of our nature while probing the question: where does the character end, and the person begin? And that is pure jazz!!!

To balance reality and fiction in both the writing and shooting process, I began by interviewing cast members and collecting secrets and confessions from people I knew, using these as inspiration to ground the narrative in authenticity. I also involved non-actors by creating spontaneous situations before filming and giving them complete freedom to speak and act as they wished. The writing process unfolded alongside the research and before, allowing us to craft dialogues that resonated with the themes and realities we explored. On shooting days, I introduced an element of surprise by giving actors small notes with opposing secrets before certain scenes.

Cinemacy: The film features a diverse ensemble of characters. How did you go about casting the actors, and did any of them share personal confessions or stories that directly influenced their performances?

Carolina Perelman: It's difficult to pinpoint an elaborate answer because the process was simple: I chose actors who shared a meaningful connection with some aspect of the project or that I genuinely really like because I think they are either fun or creative.

Some cast members contributed personal experiences that influenced their performances, while secrets and confessions guided others I had collected from other people during my research. Of course, these stories were shared anonymously to respect the privacy and identity of the participants, ensuring a safe and respectful creative process.

Cinemacy: Jazz plays a crucial role in the film, not just as a soundtrack but as a thematic device. How did you collaborate with the composer or sound team to ensure that the music captured the frenetic, free-form energy of the characters’ emotions?

Carolina Perelman: Jazz was essential in shaping the film’s atmosphere, and, OF COURSE, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis were our core inspirations. The conversations in the film don’t have clear beginnings or endings, which, in my opinion, is characteristic of the nightlife in Madrid and jazz.

It’s like having a deep conversation with a random person in a bar—you may not remember how it started or how it ended, but it resonates with a kind of chaotic harmony. When I read Julio Cortázar’s short story “El Perseguidor,” I remember feeling intense energy and adrenaline, as Parker’s jazz also inspired him. I wanted to capture that same sensation in the ambiance of Cazador bar…or something similar to that energy.

Cinemacy: Given that the film explores both the absurdity and the pain of human relationships, how did you approach the tone? Was it challenging to find the right balance between humor and the more serious moments of the story?

Carolina Perelman: Not at all. I think it was like opening and closing drawers. In real life, you can cry and end up laughing. The same thing happened in Confesiones Chin Chin.

Cinemacy: The "chin chin" toast symbolizes relief and unburdening. How did you use this concept symbolically throughout the film, visually and narratively, to underline the theme of confession and honesty?

Carolina Perelman: "Chin Chin" is like saying “cheers.” Without planning, I realized that “chin chin” is like breathing out when you get something off your chest—something you really wanted to say but were too embarrassed or scared to, fearing it might hurt someone. Then you finally say it and exhale. In the film, we’re in a bar, so instead of feeling like a yoga class, we celebrate people’s flaws and virtues, because no one is perfect or an angel.

That’s why I wanted to start closing the film and the chaos with archival materials of some cast members as kids, to remind ourselves where we come from—a genuine and innocent place, the “unburdened place.”

Cinemacy: You mention using humor to address complex topics like sexuality, abuse, and fidelity. Can you speak more about how you approached writing and directed those scenes to maintain respect while allowing for moments of levity?

Carolina Perelman: I approached people’s secrets and confessions with deep respect, ensuring their essence was preserved. Meaning that if the person who confessed to me something with humor, I wanted to respect that. For instance, Roberto’s confession about being abused in a hotel in Peru was inspired by the real person’s ability to weave humor into their vulnerability.

Also, in my personal experience, the best way to cope with trauma is with a little bit of humor. Why is humor disrespectful? I think it is the best way to break the ice and allow people to share. But that is my opinion relying on the research I did.

Cinemacy: You’ve spoken about the idea of “self-conscious behavior” in the film. What direction did you give the cast to encourage them to embody this self-awareness, especially since many characters reveal deeply personal, often uncomfortable truths?

Carolina Perelman: The less information I gave them, the better because it allowed for a rawness to emerge—the nakedness of the soul. I had the opportunity to have long conversations and interviews with some of them for 3-4 months. I think it was enough information, and during the shoot, I wanted the actors to shed their defenses and preconceived notions about their characters.

I didn’t want to rehearse or give any direction, just a preamble or a little secret to some of them before each scene... Often, I withheld key details until the moment of filming, so their reactions carried a genuine immediacy. This demanded immense trust, but it allowed them to embody vulnerability in its truest form, where the deeply personal and uncomfortable could surface authentically.

Cinemacy: What is the most important thing you learned after making this film?

Carolina Perelman: The most important thing I learned is that instinct—that thing you sometimes don’t fully understand but drives you to create art or take action—is what you have to follow when making a film or any kind of art. Listen and observe what’s around you…and most importantly, listen to yourself.

Cinemacy: What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

Carolina Perelman: Nothing in particular, but perhaps a little less alone and embarrassed when they think about their dark secrets (if they have any). And toast to the freedom found in honesty! Fuck it, we are gonna die one day…might as well say and do what we want when we feel like it.

Cinemacy: What advice would you give fellow filmmakers who want to make their first feature film or break into the industry?

Carolina Perelman: Do it no matter what! Don't be preoccupied with having the best camera, which is very expensive! Try to create genuine and honest art… be organized and efficient, and try to have fun! Try to avoid taking things personally. Just know it’s challenging to manage people’s egos. Breathe and find the patience inside you.

For more, visit https://produccionesnau.com/

Carol Polakoff Knows No Boundaries

Not many directors would make their directorial debut simply after hearing the book read aloud at a book reading, and fewer would decide to make a movie in a non-native language. However, Carol Polakoff did both with her feature film debut, Speak Sunlight. The film tells the life of American writer Alan Jolis as he awakens to a vivid, sensual world and grows up emotionally.

In our exclusive interview, Carol Polakoff discusses the inspiration behind making the film, the many challenges she faced along the way ("Children, animals, and historical period!"), and what the message that she hopes will endure: "Secrets and shame drag our spirits down, and transparency with those you love and who love you is hard to overcome, but the benefits are for a lifetime."

It’s a pleasure to meet you, Carol! What inspired you to create Speak Sunlight? Was there a specific event or moment that sparked the idea?

Carol Polakoff: Yes, very much so. 22 years ago, I met the author, who became a dear friend on the occasion of a book reading at a Paris bookstore. Within minutes, I was in tears. The story hit me so raw and powerful. I never had such a reaction before (or since) at a book reading.

I made a vow many years ago that I would make this movie, not knowing it would be my directorial debut. A vow that was made as the very young (45) author was diagnosed with cancer and subsequently passed away. I promised him his life would be memorialized on the screen.

Memory and exile are central to the story. How did you explore these themes in the film, particularly in the scenes set in Spain and Paris?

Carol Polakoff: I think that is carried by the characters Maruja and Manolo. They have exiled themselves from a country they loved but did not love them back. Manolo fought in the resistance against Franco, and Maruja was running for more personal reasons She was ashamed about her actions during the war, i.e., getting out of her small town to Pamplona by “stealing” her sister's fiancee.

How did you collaborate with the cast to bring the nuances of these complex characters to life? Were there specific moments or performances that surprised you during filming?

Carol Polakoff: There are always surprises with great actors, and Carmen and Karra are legends and masters. There was a language barrier (my Spanish was way under par), so we had translators. But, it made the burden of great communication with our hearts and minds more important and rewarding.

How did your process differ as a screenwriter from when you were directing the film? Were there moments during the writing phase that changed once you were on set?

Carol Polakoff: Yes. I had the freedom to improvise and see what worked in real time. Actors often know best what feels authentic for them and their range, and writers should be flexible and not married to their own words. You take on actors to add a layer to the material, not reproduce it.

Filmmaking is always a collaborative process. How did you work with your cinematographer, production designer, and other key team members to create the visual and emotional tone of the film?

Carol Polakoff: I had the best team in the world. The cinematographer and editor were my heroes, having made films with Almodovar, and they helped me more than I can say. The designers, both set and costume, were brilliant, and all of the above were suggested by my producer, who had worked with them on many productions, large and small.

Every film has its challenges. What were some of the biggest obstacles you faced during production, and how did you overcome them?

Carol Polakoff: The language! The pandemic. Fires in our locations and 110-degree weather. And the usual… first-time director, directing in a language other than her own… and the three cardinal rules for a first-timer: Children, animals, and historical period! Not to mention staging the bull run with our bulls and stunts.

What do you hope the audience takes away from the film? Is there a particular feeling or insight you want viewers to experience, especially about the themes of love, loss, and healing?

Carol Polakoff: Yes. I hope they see themselves in Alanito, Maruja, and Manolo and forgive the past and people so that the present and future can be as rich and rewarding as possible. Secrets and shame drag our spirits down, and transparency with those you love and who love you is hard to overcome, but the benefits are for a lifetime. Realize that the time you spend together creates future memories and is the currency you bank on when they are no longer here. Love and loss are part of life. Honor them.

Zayn Alexandre Overcomes Oppression By Defying Limits

Growing up in a small town outside of Beirut, Lebanon, where he witnessed the cultural repression of women firsthand, filmmaker Zayn Alexandre has gone on to write and tell stories that celebrate humans overcoming oppression. His debut short film, the intimate sociopolitical drama Abroad, tells the story of a Lebanese immigrant couple. His second directorial effort, Manara, debuted during the 76th Venice Film Festival in the Giornate degli Autori section.

Now, Alexandre returns with his new film, Saint Rose. In our exclusive interview, the writer-director discusses how seeing the women in his life confined influenced the story, working with his mother on a personal experience, and how the film is about "the human desire for freedom and self-actualization."

What inspired you to create Saint Rose? Could you talk about the personal experiences that led to the creation of this story?

Zayn Alexandre: Saint Rose was inspired by the women I grew up around, who navigated societal norms and expectations by succumbing to them or through quiet defiance. Seeing my mother and other women in my life unable to reach their full potential because of roles imposed on them profoundly influenced me.

Life became a state of confinement for them, with moments of joy reduced to small, fleeting pockets of freedom they had to seek. My mother and sister, in particular, inspired me with their resilience and strength in the face of rigid norms. This project is deeply personal and rooted in what I witnessed growing up.

The film deals with control, oppression, and breaking free from societal expectations. How did you approach weaving these heavy themes into a short film?

Zayn Alexandre: I focused on telling an intimate and relatable story. Every detail, from the setting to the characters, was designed to subtly reflect these struggles. I wanted the themes to emerge organically through Rose’s daily life.

Much of the story lies in what’s not being said. I hope the audience can feel Rose’s sense of confinement through these nuances. I would describe the film as both subtle and restrained.

The relationship between Rose and her housekeeper, Becky, is central to the film. How did you portray this relationship, and what did you want each character to represent?

Zayn Alexandre: Despite their different backgrounds, Rose and Becky are trapped by their circumstances. They are prisoners in their ways, shaped by societal expectations and personal struggles, and they’ve developed a mutually dependent relationship.

What might seem like a typical employer-employee dynamic reveals more profound similarities. Their shared sense of entrapment blurs the lines between wealth and privilege, creating a complex and deeply human bond between these women.

You mentioned this film was a love letter to your mother and sister. How did working on such a profoundly personal project affect you emotionally throughout the filmmaking process?

Zayn Alexandre: Tapping into deeply personal issues, which are still ongoing, was very challenging. Working with my mother on a story so closely tied to our own experiences added another difficulty—I had to constantly navigate separating my role as “director” from my role as “son.” It was emotionally taxing for everyone.

The film features crucial roles played by non-professional actors. How did you approach working with them, and what challenges or advantages did that bring to the production?

Zayn Alexandre: Working with non-professional actors is challenging but rewarding. Intuition is a pretty powerful tool. Because the story was close to home to both actors, their performances came from a place of passion. Rehearsals were minimal.

It was important to create a safe environment where they felt comfortable and were not camera-conscious. Their performances needed to feel raw and genuine.

You mentioned using symmetrical and polished cinematography at the start of the film to represent Rose’s entrapment, which becomes more chaotic. How did you collaborate with your cinematographer to achieve this visual shift, and what was your intention behind it?

Zayn Alexandre: My cinematographer, Karim Kassem, and I intentionally used symmetry and rigidity in the film’s early scenes to amplify Rose’s controlled, stifling world. As the story unfolds, we opted for handheld movements and less polished framing to reflect her emotional unraveling and eventual chaos.

The film's tone shifts from severe to almost campy and satirical by the end. How did you balance these tones, and why did you choose to end the film in such a way?

Zayn Alexandre: Life is rarely one-note, and I wanted the film to reflect that. The tonal shift mirrors Rose’s breaking point. By leaning into the satire, I aimed to highlight the situation's absurdity and life in general.

Rose’s relationship with alcohol, particularly her secret consumption of vodka, is a significant element in the film. What does alcohol represent in the context of her emotional journey, and how did you want audiences to interpret her use of it?

Zayn Alexandre: Alcohol is both a form of rebellion and escape. It’s Rose’s secret act of defiance in a life otherwise dictated by control and appearances. At the same time, it’s a coping mechanism, a way to numb herself to her reality.

Finally, what do you hope audiences will take away from Saint Rose? Is there a specific emotion or thought you want them to leave the theater with after watching Rose’s story unfold?

Zayn Alexandre: I hope audiences leave with empathy and reflection. Rose’s journey is deeply personal but universal. It’s about the human desire for freedom and self-actualization. I want whoever sees the film to question the societal structures that limit us and feel inspired by the resilience of the many women in their lives.

'Wicked' Review: Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande Bring The Magic

Wicked, the long-awaited film adaptation of the beloved Broadway musical, has finally arrived more than two decades after its debut. With legions of fans—including myself—eager to see if it could live up to the hype, I’m happy to say it more than defies expectations.

Directed by Jon M. Chu, who brought boundless energy to Lin-Manuel Miranda's 2021 movie musical In the Heights, Wicked dazzles with a fresh, thrilling reimagining that will captivate audiences everywhere.

A New Take on Oz

The film opens in the iconic land of Oz, where the Munchkins joyfully sing, "Good news! She’s Dead!" after the Wicked Witch of the West’s demise. Glinda the Good Witch (Ariana Grande) arrives and reveals she once knew the notorious witch, sparking a flashback to their time at Shiz University. There, the popular, bubbly Glinda meets Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo), a green-skinned, ostracized student with magical powers far stronger than anyone’s.

What follows is an unlikely friendship between Elphaba and Glinda, who must both navigate a world of magic, danger, and betrayal. Alongside Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) and a journey to the Emerald City to meet the Wizard of Oz (Jeff Goldblum), they soon discover that not everything is as it seems.

Epic Musical Numbers, Emotional Moments

Chu brings the grandeur of Wicked's musical numbers to life with infectious energy, using a dynamic camera to highlight Christopher Scott’s vibrant, exhilarating choreography. It was thrilling to experience and had me sing and tap my feet.

Impressively, the film also balances its exuberance with emotional depth. Elphaba’s bond with Dr. Dillamond (Peter Dinklage), a professor who speaks out against the oppression of talking animals, offers one of the film’s most poignant moments.

A Faithful Adaptation

Screenwriters Winnie Holzman and Dana Fox succeed in staying true to the original musical while making the story feel fresh. The film is a faithful, immersive experience at nearly two hours and forty minutes. The standout number, "The Wizard and I," sung by Elphaba (Erivo), is a tour de force, leaving the audience in awe of Erivo’s powerhouse vocals.

Likewise, "What Is This Feeling?" and "Popular" offer a new take on the rivalry-turned-friendship between Elphaba and Glinda. "Dancing Through Life," led by Jonathan Bailey’s charming Fiyero, is thrilling. And, of course, the climactic "Defying Gravity" is breathtaking and everything fans could hope for.

Stellar Performances

At the heart of the film’s magic are its leads. Ariana Grande shines as Glinda delivers her trademark charm and wit, while Cynthia Erivo’s portrayal of Elphaba steals the show. Erivo brings an extraordinary depth to the character, blending vulnerability and strength in a performance that is nothing short of masterful.

Erivo’s portrayal of Elphaba is a career-defining performance that warrants serious award consideration. While Grande is excellent, it’s Erivo who indeed commands the screen.

Minor Criticisms

While the film remains faithful to the original script, this sometimes leads to pacing issues, with certain scenes feeling drawn out. The cinematography is striking, but the color grading occasionally feels flat, detracting from the vibrant, magical world that Wicked should evoke.

Conclusion

Wicked is a triumph. Jon M. Chu’s direction, combined with standout performances from Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo, captures the heart and magic of the stage musical while infusing the story with new life. This is a film that fans will want to celebrate—and sing along to while we anticipate the upcoming sequel.

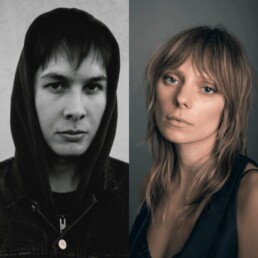

Ben Tan and Alexis Felix Capture Raw Emotions of Teenage Life

"The LA rave scene exposes you to all kinds of new, often dangerous experiences. But as a teenager, I was always drawn to that danger—it felt rebellious and offered a way out of the mundane," says Ben Tan, a filmmaker who, in his youth, navigated the magnetic yet dangerous world of LA raves. For Tan, it wasn’t just about seeking thrills; it was about escaping the anxiety and pressures of adulthood. His debut short film DOG, which he wrote and directed, tells the story of 19-year-old Summer, who takes her blind younger sister to a rave, only to see the night spiral into chaos.

In our exclusive interview, Ben Tan and star Alexis Felix share insights into the making of DOG and their own experiences that they brought to the making of the film. As Ben reflects, "DOG is a reflection of my adolescence—those nights in Los Angeles filled with raves, music, and drugs. It’s about chasing fleeting moments of ecstasy, only to be met with despair. Ultimately, it’s a story about the unavoidable reality of growing up."

Congratulations to you, Ben, on your short film, DOG, which tells the story of a 19-year-old girl taking her blind younger sister to a rave, only for chaos to ensue. In your director's statement, you say how you spent your adolescent years in Los Angeles, “Chasing moments of ecstasy. Arriving at despair.” What inspired you to tell this story?

Ben Tan: I wanted to capture my anxieties growing up and confronting adulthood. The LA rave scene exposes you to new things that might be dangerous, but as a teenager, I was always drawn to danger because it was rebellious and offered an escape from normalcy.

But the dread starts to creep back in when you’re back home lying in bed. Parents never fully know what’s going on in their kids' lives, and the secrets we keep are painful.

Ben, what was your creative process for writing the script and the character of Summer? When did you first meet Alexis and know she was the one for the role?

BT: Alexis and I met in high school. A single mother raised her, and she has a sister. We both shared a love for electronic music and had rebellious childhoods.

When I started writing, I made location and casting decisions early because I knew that if Alexis played Summer, I could cast her real mom and shoot at her childhood home. This made writing natural because I wrote with actors and locations in mind.

Alexis, what were your first thoughts while reading the part of Summer in the script? What was the most alluring part of the character, and what were you most excited to bring to the performance?

Alexis Felix: I knew Ben was in the works of writing this script, and initially, it was a story with two brothers. One day, he came home from work, told me he changed some things, and asked if I wanted to read it. My face lit up when I started reading the script about two sisters. I immediately knew I could play Summer. The character resonated with me a lot because I had grown up as a younger sister with a single mom in my own life.

I always wondered what being our family's older sister would be like, which allowed me to explore that. Summer’s mom in DOG is my mom in real life. I was so excited to share the movie-making magic with her and show her all the hard work I had been doing behind the scenes.

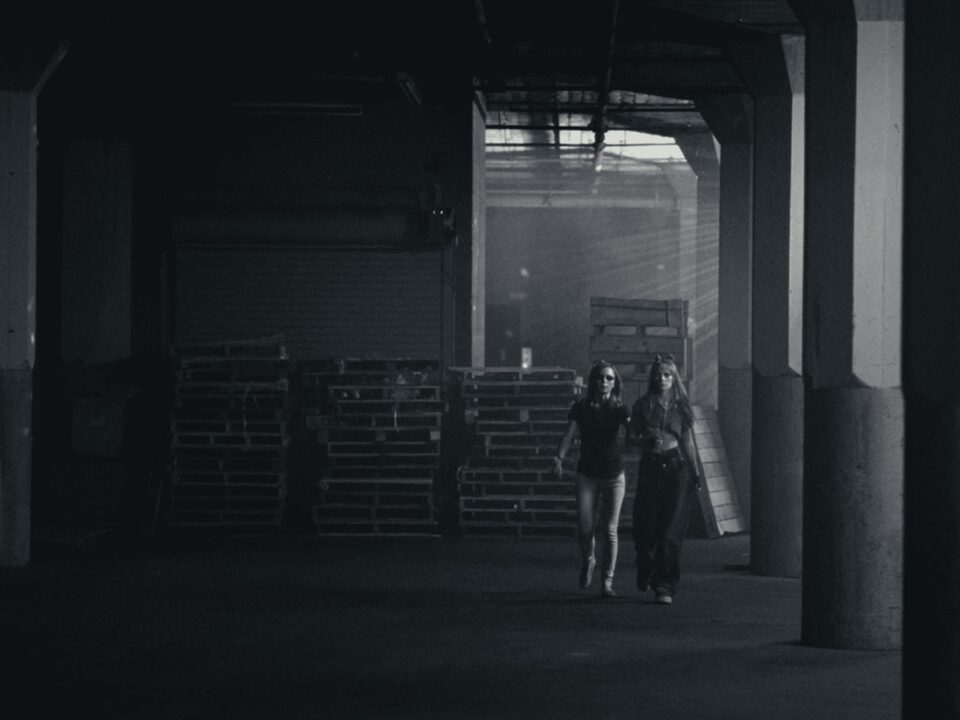

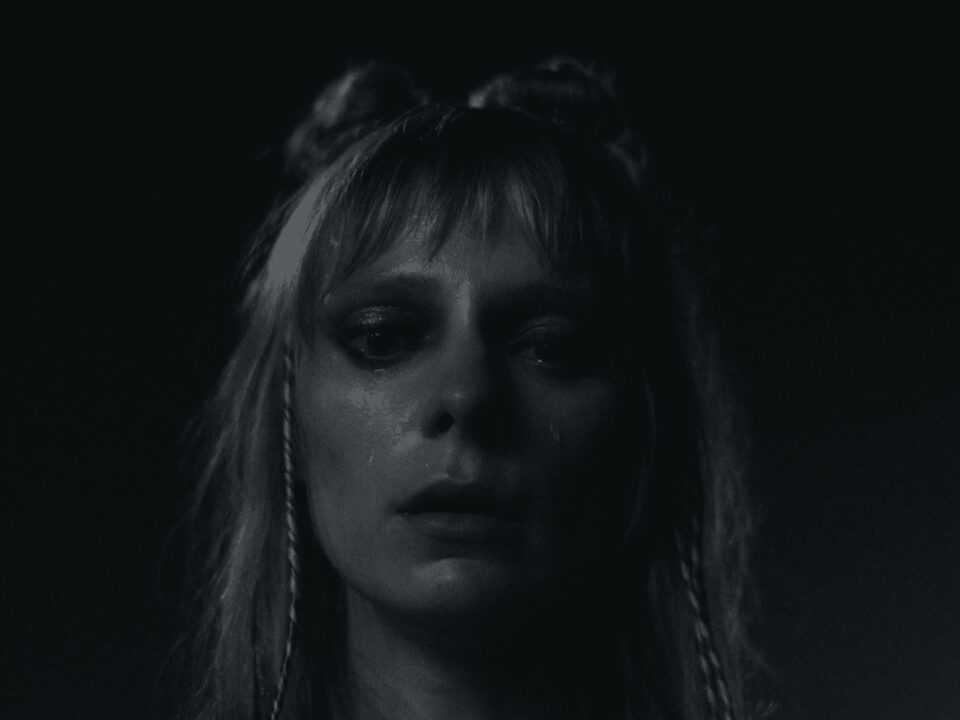

Ben, the film looks beautiful and distinct, with its black-and-white photography and 4:3 aspect ratio. How did you decide upon this look for this story?

BT: I chose a narrow aspect ratio to emphasize teenagers' claustrophobia when surrounded by family and friends but needing an escape. Black and white was an aesthetic that had character motivation. Lex is blind, so she’s missing a sense. Stripping away the color helps the audience see through her perspective. It also adds to the theme of growing up and the dark cloud of angst that looms over our heads.

Alexis, can you talk about your creative process with Ben on set? What challenges did you face in this rave-set film?

AF: Ben and I have very similar tastes, so working with him creatively was fun. I loved that he gave all the actors on the set free range to be themselves and creatively mold the characters as they imagined them to be. He’s the writer and director of the project; however, he was interested in seeing how we all perceived the characters that he wrote.

As for challenges, I think everything ran very smoothly. Because we were on a time crunch, we only had 2-3 takes per scene, so we all had to be on our game.

Ben, can you share any challenges you faced during production, especially when shooting in a rave environment?

BT: We filmed the rave throughout an overnight shoot. A dozen or more friends donated their time to be background actors. We weren’t supposed to have fog at the location, but the lasers and strobes didn’t pick up in the camera without it. We ended up triggering the fire alarm three times. The third time, a squad of firefighters came to set, and they told us that if the alarm were triggered again, they’d shut our production down.

Luckily, the fog stayed in place, and we could finish those scenes. There was a moment in the night when I thought it was over and we’d have to scrap everything. Without the rave scenes, there would be no film.

How do you think the film speaks to the universal experience of growing up and the struggles that come with it?

BT: DOG is set in a specific time and place. Growing up, I watched films like Larry Clark’s Kids or Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen. Both of these films highlight a particular subculture, making them believable.

They’re time capsules, and those films make me feel understood. No matter where you are in the world, the struggles of a teenager are universal.

AF: Morality plays a huge part in becoming an adult. As a teenager, you constantly make decisions and choose right from wrong. Whether dealing with peer pressure, navigating the people you choose to hang out with, or the situations they can put you in. As much as our parents try to teach us right from wrong, teenagers must go through life experiences to determine the consequences for themselves.

It’s like when you were a toddler, and your mom tells you not to touch the fire because it’s hot, but you do it anyway. We instinctively need to experience something to learn. I think this film does an excellent job of exploring that.

What are your hopes for DOG's future and how it might impact discussions around youth culture and coming of age?

BT: I’m always interested in coming-of-age stories that are specific and illuminate the subcultures we cultivate as teenagers. I’d love to see more of that.

AF: I hope people can see DOG and that it sparks a discussion of morality and the decisions we make as teenagers.