With little exception, the characters around Anna, the young protagonist of When Marnie Was There—Studio Ghibli’s latest and last film, at least for a little while—find her off-putting, and she is off-putting. Her own insecurities, most of them related to her background in the foster system, often manifest themselves through panic attacks and puzzling disdain for those who try to befriend her.

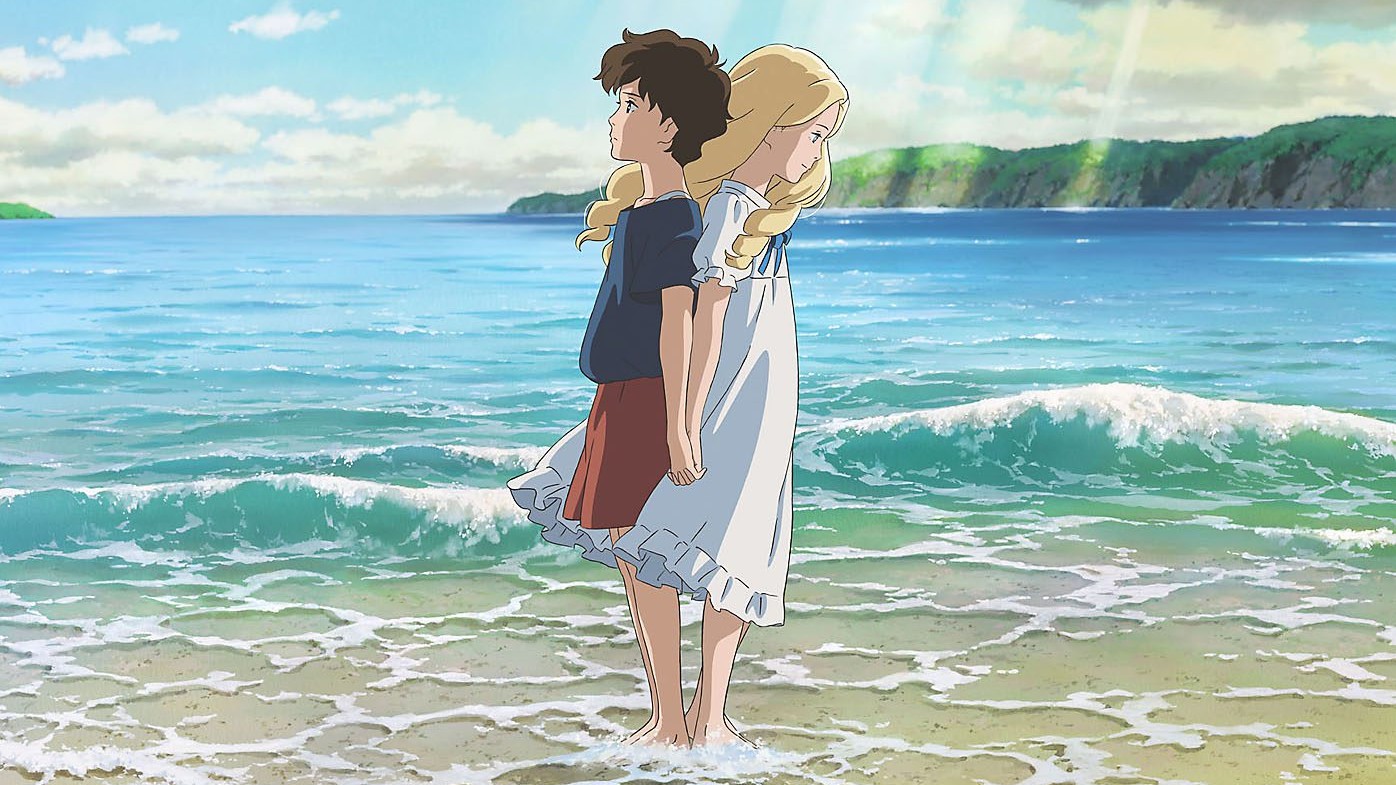

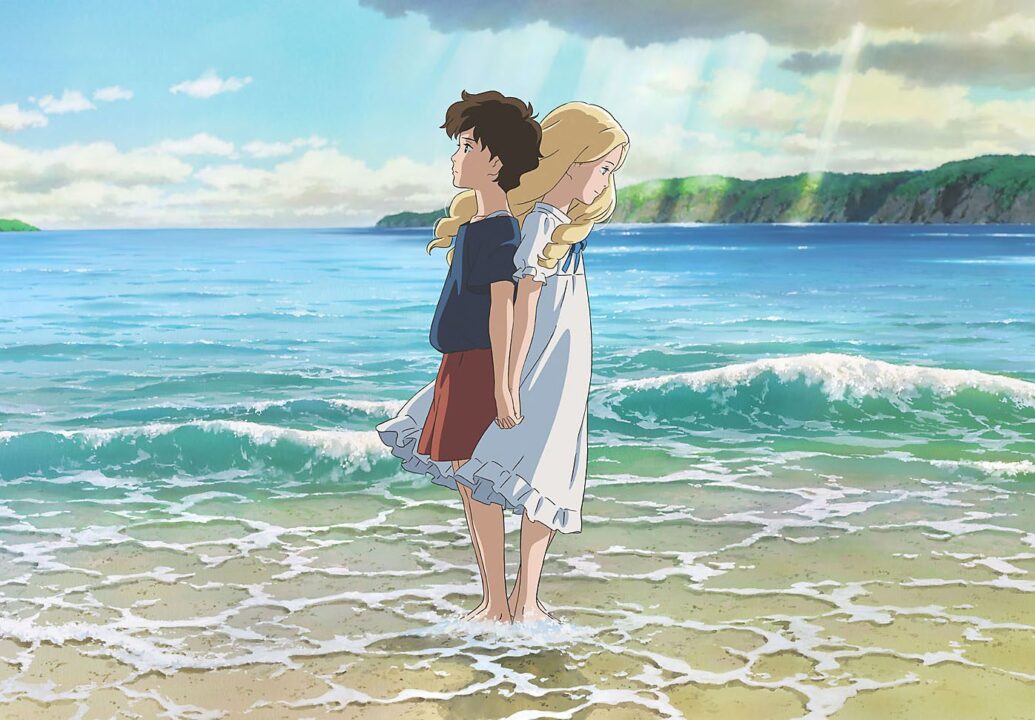

While Anna may be alienating, particularly compared to the long line of other, warmer Studio Ghibli female lead characters, the world she occupies is anything but. Ghibli’s films have always been lush and lovingly drawn, but When Marnie Was There seems especially beautiful. Each surface and every detail has an indescribable texture like a more vibrant, inviting version of real life. It’s easy to detect every ripple of water, or to feel every impact of a gust of wind on the characters.

Hirosama Yonebashi’s second feature as director after the more lighthearted The Secret World of Arrietty is also one of the studio’s first since the retirement of founding pioneer Hayao Miyazaki. If anyone doubted Yonebashi’s talent as an animator (but why would they?), When Marnie Was There provides further proof, as the world he creates is stunningly rendered, though the creativity of the characters and the creatures within it don’t match the level of sheer invention established by Miyazaki’s best work. To be fair, it shouldn’t have to be. While Miyazaki’s work was far more fantastic, Marnie has its roots in Victorian-style classic literature, as it is based on a novel written by British author Joan G. Robinson in the 1960s.

Each surface and every detail has an indescribable texture like a more vibrant, inviting version of real life. It’s easy to detect every ripple of water, or to feel every impact of a gust of wind on the characters.

While the film’s landscapes may be open and inviting, the story is less so initially, but as the details begin to unfold and the characters develop it does open up. Anna is sent by her guilt-ridden foster mother to stay with relatives in the countryside to help both of them get well after some recent psychological troubles.

Though Anna’s new guardians are friendly as can be, she still feels like a hopeless outsider, and compulsively does her best to remain one. That is, until she meets a radiant young girl named Marnie, who lives in a mysterious mansion across the lake, with whom she has an instant connection with. Of course, their friendship is made difficult by the strange supernatural goings-on that slowly seem to drive them apart.

Although the plot never once becomes truly surprising, the familiar story is deepened by the richness of emotion that slowly develops over the course of the movie. Yonebayashi cultivates a very distinct, eventually engrossing, atmosphere with almost every facet of Marnie that when the emotional revelations pay off in the third act, I found myself particularly invested in the characters and their emotional states. Anna may be difficult, but her relationship with Marnie allows her the depth any good protagonist deserves.

This isn’t a perfect film by any means. The film suffers from story flaws in its occasionally slow pacing and muddled, disorienting chain of events a little past the midpoint, though such flaws are easily overlooked for the most part.

I can easily imagine how some viewers might be unaffected by the inexplicable emotional connection I felt while watching When Marnie Was There, but it’s hard to deny the film’s aesthetic beauty and emotional delicacy. At its best, When Marnie Was There feels like a half-forgotten memory of an idyllic childhood dream—nostalgic, beautiful and tragic in the deeply felt passage of time and its suggestion that ideas like love and family can somehow transcend it.

When Marnie Was There is now playing at Laemmle Theatres.

Jeff Rindskopf

Jeff Rindskopf is a contributing writer for CINEMACY.