The UFO genre has always had a divided soul, split evenly between bleak body horror and wholesome tributes to connection. With his invigorating period piece, The Vast of Night, first-time feature director Andrew Patterson parachutes into this divide and sets up camp by offering story beats that invoke both the light and dark potential of the genre. The film’s brilliant title sets the mood just right. Depending on the reading and intonation, The Vast of Night, could sound hopeful, full of starlight and promise, or intimidating, tinged with unknowable threat.

While I won’t tell you if The Vast of Night is an E.T or an Alien, or confirm if it has creatures at all, I can tell you it’s a film obsessed with wonder, terror, and the fine line between the two. It’s also better at evoking these sensations than 95% of its modern, big-budget counterparts. Set in 1950’s New Mexico, this Twilight Zone inflected story recounts the events of one dizzying evening, in which a young switchboard operator, Fay (Sierra McCormick), hears a radio signal of unknown origin. She ropes in local radio host, Everett (Jake Horowitz), to investigate and they soon find themselves fielding calls from impassioned strangers who claim to know something about the classified history of these signals, and the lights in the sky that accompany them.

The most winning element of The Vast of Night is the way it infuses you with wonder. It captures that breathless, fantastic emotion so well, from the way it shocks us into stilled awe to the way it animates our curiosity. It’s no wonder (haha! I’m so sorry) that the film won the top Jury Prize at the Overlook Film Festival while coming in second for the audience award. I’d challenge anyone to sit down to this film’s first act and not feel giddy, especially once they meet Sierra McCormick, the heart and soul of the film and the embodiment of wonder. This intrepid teen reads everything and lights up when discussing future-facing reports on science & technology. Her eagerness to learn has already attracted the mentorship of radioman Everett before the film begins, establishing a dynamic duo of truth-seekers who could easily headline the Men in Black franchise.

Much credit for this infectious energy also goes to the camerawork. The first act is stacked with ambitious long takes that establish the small town and roving characters with verve. Adam Dietrich’s resurrection of a 1950’s town on a shoestring budget for these shots is glorious, by the by, and apparently involved mini-quests like the production team covering a road with gravel to hide anachronistic parking spots. The film’s most complex take runs from Fay’s office to the high school where the town is gathered to watch a big game (if they could only fix the mysterious electric issues), and beyond. In the post-film Q&A, the team detailed their avoidance of drone footage and other tech trends that could become a crutch. To accomplish this take, they turned to every grounded tool they knew of (which was many, as Patterson had worked in commercial and corporate video for over a decade and founded his own production company). They also recruited every resource in the small Texan towns of Whitney and Hillsboro, including tractors and an 18-year-old go-kart driver. These roving takes never feel like showiness for its own sake. Rather they feel perfectly judged as an energetic infusion into a film that also values and loves stillness.

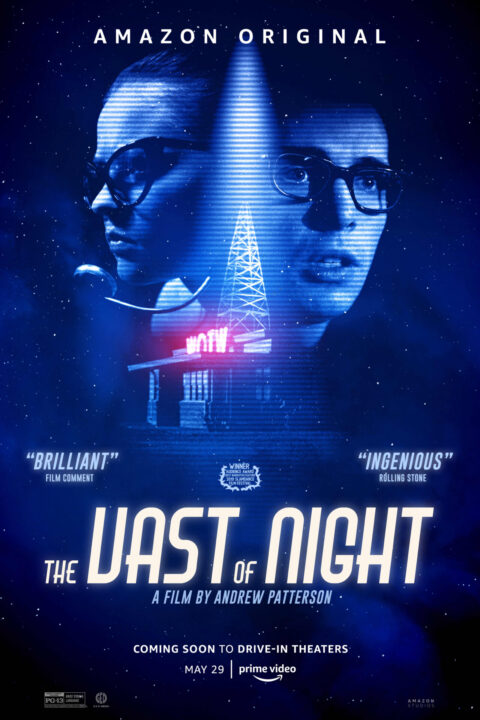

As you may have surmised from this description, and from the film’s stylized poster of a radio tower, radio is a major influence on this narrative. And it’s radio that creates the film’s treasured pauses, where 10-minute monologues breathe in near absolute stillness. Several times, the screen goes black to allow complete engagement with sound and imagination. It’s a confident and assured maneuver. It’s also aggressively out of line with most trends in genre filmmaking. Today, most action and sci-fi blockbusters hold shots for an average of 3 seconds, constantly refreshing the visual field. While this speedy average shot length isn’t inherently good or bad, it can sometimes be coupled with a dogmatic belief that nothing should be left off-screen, leaving little opportunity for the audience to activate the picture-making parts of our minds that novels and podcasts thrive on.

The Vast of Night puts a lot on its performers in asking them to hold such prolonged attention, but the troupe carries it off magnificently. Some of the tensest scenes feel like a great radio drama, in which a character reveals their long-withheld life story for an open-minded interviewer. Gail Cronauer and Bruce Davis, in particular, own the movie for 10 minutes each as they share their personal history with the mythos of the area. I can’t say more about their performances without spoiling the turns of the plot, but these enveloping monologues do a marvelous job at complicating Fay’s idealism and Everett’s confident problem-solving.

Both Fay and Everett exhibit a voracious hunger for the future, for technology, for a wider world. Early on, they discuss Fay’s belief, based on magazine reports, that underground trains will whisk people across the world at speed and pocket TV screens will connect the globe. I suspect that I, and many people, will be caught up in good-humored nostalgia at Fay’s version of the 1950s, and at the idea that there was a time when people did feel such unbridled optimism for the future. It’s a far cry from the defining anxieties of the present, especially climate catastrophe. Yet, as the film goes on, the focus expands to the fundamental fault lines of that era and our own, including the single mothers, native people, and African American men violently pushed outside of the supposedly every more connected American tapestry.

The Vast of Night is a film of complex moods and messages. It’s enamored with the restorative joy of Fay’s hope for the future, but also full of reminders that the connected world she longs for isn’t guaranteed to be just. That connection, whether made through radio waves or small-town sports, is just as capable of fostering division as progress. But, as the film insistently repeats through its sound design and style, no matter what era, face to face and voice to voice storytelling will always offer some of our best hopes for sifting out the truth. With smarts and style, The Vast of Night makes itself necessary viewing, and listening, for fans of Spielberg, Welcome to Night Vale, or just formally bold independent debuts.

89 minutes. Currently seeking distribution.

Kailee Andrews

Kailee holds a Communication Arts B.A. from the University of Wisconsin. At 21, she programmed her first film festival for an audience of 4,000+ on campus. Since then, it's been all about sharing the cool arts and crafts of cinema.