Review: 'Being Canadian'

Being Canadian is a pleasant way to spend 90 minutes of your time, but it isn’t a particularly compelling documentary. It’s shapeless by design, attempting to make sense of the heritage, reputation and history of America’s oft-forgotten neighbor to the North.

Much of the shortcomings are due to the minimal screen presence of director, writer and star Rob Cohen, a TV writer who embarks on a trans-Canadian trek in an effort to understand and explain his homeland to the sorts of Americans who think Canada is nothing more than a frozen tundra filled with polar bears and people who say “eh.”

Cohen seems like a nice enough guy, but he simply doesn’t have the charisma to lead a movie like this. His road trip from Nova Scotia to Vancouver in honor of Canada Day is often painfully awkward, as he simply can’t spout quips or react well enough to sell any of the comedic set pieces shoehorned into his film.

These scripted comic sketches, like one where Cohen goes on a maple syrup binge or one wherein Wayne Gretzky appears in the sky to offer advice (much in the style of God from Monty Python and the Holy Grail), are meant to give the film some sort of shape and structure. Unfortunately, they feel labored—and no good documentary should really feel labored.

I found myself relating to celebrities I’d never much cared about before—Howie Mandel, for example, manages to score roughly the biggest laugh in the entire film.

It’s easy to spot the parts where some creative editing and voiceover narration were substituted for substance in order to make the journey somehow satisfying. It may have been Cohen’s TV writing instincts kicking in, distracting from a documentary, where the narrative needn’t be so straightforward.

Rob seems especially out of his depths in comparison to the dozens of more charismatic Canadian celebrities populating other parts of the film. He’s managed to secure interviews with scores of famous Canadian personalities, which are spliced into the film at random. Everyone from Seth Rogen to Alex Trebek, William Shatner to Cobie Smulders chimes in to address common questions about Canadian stereotypes and history.

Even when their insights aren’t particularly, well, insightful, they’re still affable, friendly and funny enough to entertain with their mere presence. I found myself relating to celebrities I’d never much cared about before—Howie Mandel, for example, manages to score roughly the biggest laugh in the entire film.

I think I know plenty about Canadian culture and history compared to most Americans—certainly compared to the Americans used in this film to illustrate how misunderstood Canada is—which might explain why I didn’t take away too much from the film, except maybe about the existence of a Canadian television classic called Beachcombers (which sounds amazing in its utter blandness). In aiming to confront Canadian stereotypes, Cohen and the other filmmakers mostly just confirm them.

Yes, Canadians are meek and overly polite. Yes, they love hockey. Yes, the weather is cold. No, they don’t have much of a national cuisine outside of Canadian bacon, poutine and maple syrup (their Fort Knox-equivalent is a stronghold of maple syrup). But there’s more! I didn’t necessarily need to watch this film to learn that there’s more to Canada, and I don’t think anyone else needs to either.

With all that said, despite its flaws, Being Canadian is an easy, even comforting watch, if only for the celebrity talking heads and a few worthwhile Canadian history lessons—the way they became a nation almost as an afterthought of the British crown is particularly amusing. It’s nothing if not open and warm and friendly, even if it pales in comparison to documentaries with bigger budgets and greater worldwide acclaim. Remind you of anything?

Being Canadian opens today at the Crest Westwood in Los Angeles and available on VOD.

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/beingcanadian/131433063

Review: 'Phoenix'

The title of Phoenix, the newest film from German director Christian Petzold, can refer to many things. Most directly, it refers to the glowing red sign overhanging the entrance to postwar Berlin’s seedy American district. The word also carries connotations of rebirth, for the German nation, for the Jewish people, and for one woman.

That woman is Nelly Lenz, played by Nina Hoss, a holocaust survivor returning to Berlin in the wake of the war for facial reconstruction surgery. Accompanying her is Lene (Nina Kunzendorf), her Jewish friend mourning the loss of so many of her people. Unlike Nelly who prefers not to identify as Jewish, Lene doesn’t wish to return to German society and even finds it disturbing to see how others can carry on as if nothing has happened.

Recovering from the surgery that’s left her nearly unrecognizable, Nelly goes in search of her husband, knowing full well that he is almost certainly the one who betrayed her to the Nazis after years of successfully hiding from them. She wanders through the ravaged ruins of Berlin at night, when the streets are populated by crass soldiers and criminals. The journeys bring her to that American district, and eventually she sees her husband doing menial work at one of the nightclubs.

Phoenix is a film of restraint, and sometimes it suffers for showing less rather than more.

He no longer recognizes her, and she makes no attempt to properly identify herself. Soon, her husband Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld) decides to use her for a convoluted but still somewhat plausible plan. He will train Nelly, who he knows only as Esther, to act, write, walk and speak like his wife Nelly, who he assumes is dead, so he can collect the $20,000 owed to her by the government.

Johnny is undoubtedly a monster for his past and even current actions, but Petzold and Zehrfeld are careful never to paint him as a villain. He is more a snake than anything, difficult to understand despite actions that speak for themselves, but he is a snake that has emotions and appears to carry some amount of guilt for his past.

Opposite him, Nina Hoss plays Nelly with the vulnerability of someone who has truly seen hell and back. The trauma she’s suffered is present in every shot wherein she appears, and it makes her act as a subservient to her traitor husband. She is a woman

Phoenix is a film of restraint, and sometimes it suffers for showing less rather than more. Petzold prefers to let certain aspects of Johnny and Nelly’s relationship remain enigmatic, and the same goes for Nelly’s concentration camp past. In a film that is in many ways about a woman and a people confronting their difficult past even as the rest of society appears eager, it’s a little puzzling why Petzold shies away from and even ignores some of this story’s more difficult aspects.

I don’t mean to say that he should have made a concentration camp film; Petzold is interested in Nelly’s recovery rather than her plight. He reconstructs postwar Berlin with rich details, using crisp gloomy light for daylight scenes and suggestive shadows and streetlights during night scenes. The costuming is similarly detailed, and the visual details are supported by those small narrative ones that subtly fill out the world of the film and its themes. People almost never ask about Nelly’s past in the concentration camps. It’s almost essential for a woman to carry a gun. Before one character commits suicide, they’re sure to write a letter of recommendation for a maid who will soon have to struggle for new work.

Nelly is a weak character, but understandably so, and Phoenix devotes its runtime to challenging her to move on from the past. Like so many people, she wants to recapture life before everything went wrong, and she suffers a difficult time before she can learn that she can’t go back. The parallels with the plight of the Jewish people seems clear, but Petzold doesn’t sacrifice his characters in service of allegory. His film is better for it.

Phoenix is now playing at Laemmle theaters in Los Angeles, Orange County, Pasadena, and Encino.

https://vimeo.com/104179101

Review: 'Creep'

Creep is billed as a horror comedy built around a premise familiar to both filmgoers and news junkies—an average Joe answers a Craigslist ad and winds up in the company of somebody who seems a little bit off. The comedy half of the film’s genre billing made me expect a shred of originality and even subversive commentary that simply wasn’t there. Indeed, there isn’t really much of anything in Creep.

Co-writers Patrick Brice and Mark Duplass star in the 75 minute film as the hapless cameraman Aaron and the unsettlingly intense man on the other end of the Craiglist ad Josef, respectively. Desperate for cash, Aaron drives to Josef’s cabin in northern California for the unknown assignment. If Josef is to be believed—and he isn’t—he’s simply making a movie to be shown to his unborn son after he soon dies of cancer.

The writers describe the film as a pure character study of the men in front of and behind the camera, as it’s subtly implied that Aaron is none too well either. Brice doesn’t do much in the way of acting. Duplass, however, shows off some impressive acting chops here just as he did in last year’s The One I Love, playing an enigmatic character with a penchant for professing love to this stranger and revealing unsettling so-called truths about himself and his past. Unfortunately, he also has a nasty penchant for jump scares. It seems as though Brice, who also directs, thought viewers would be bored with the slow first half without such obnoxious “BOO!” moments.

The attempts at drawing a complex psychological portrait gives way to typical Hollywood pop-psych and lazy horror movie conclusion.

In spite of these moments, it’s the first half of Creep that really shines as a slow-burning, claustrophobic character piece, wherein Aaron suffers through a series of revealing, creepy scenes of filmmaking and bonding at Josef’s insistence. Notable examples include a lengthy, intimate ‘tubby time’ ritual and the discovery of a monstrous Halloween wolf mask called ‘Peachfuzz.’

Brice manages to keep the tension mounting, so the innocuous beginning seems to build towards a climactic second half that never comes. Instead, Brice undercuts one of the film’s most tense moments by leaving it to the viewer’s imagination—a wise move on some occasions, but a lousy copout here—and flashes forward to another location. Admittedly, I always love a film confined to a single day or location, but the move was especially misguided here.

The claustrophobia disappears, and with it so does any immediate sense of danger. Instead, Josef becomes a monster lurking in the shadows outside Aaron’s home instead of the fascinating enigma initially presented. One scene, wherein Aaron investigates his home and front yard in search of an intruder, is so wholly unoriginal another lazy jump scare would have been preferable.

The opportunity seems especially squandered since, given the first half, it looks as though Brice and Duplass might do something original with the found footage genre. Instead, they succumb to cliché despite their efforts to subvert it, which come across as misguided rather than smart. Duplass, the titular creep, often manages a tricky balancing act between overly-friendly family man and mysterious stalker. We understand how Aaron might be lulled into a feeling of safety by his character, just as we can see the early signs of his sinister intent through his prolonged eye contact, manic decisions and strange, dark sense of humor.

It all comes to nothing however, and the attempts at drawing a complex psychological portrait gives way to typical Hollywood pop-psych and lazy horror movie conclusion. The film both adheres to some of the most tired horror tropes while jettisoning others it would do well to hang onto. The result is an occasionally fascinating, occasionally maddening glorified student film that constantly undermines its own tension. Maybe it’s trying to make a statement or provoke a few laughs. In either capacity, it fails. In most capacities, in fact, Creep simply fails.

Creep is now available to stream on Netflix.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBR8VcdpE4Y

Revisiting 'Jaws': What Modern Summer Blockbusters Should Learn From the Original

For years, I passively took the old adage that Jaws represented the birth of the modern blockbuster at face value, never considering that the film’s impact was anything beyond financial. Due to its massive box office success, Hollywood took note and launched us into an enduring era of bloated budgets and event pictures that continues stronger than ever today. Re-watching the film again for its recent 40-year anniversary, I was more interested to note how the perfectly realized storytelling elements of Jaws have become the template for modern big-budget filmmaking. Like an imposing fin cutting through still water, the unique cinematic achievements of Jaws have rippled outward for so long that most of us are hardly aware of the effects anymore. But they are there, and here they are…

A New Kind of Horror

Though frequently labeled as horror, Jaws is much more than that. A standard horror film might have sparked a trend – as Halloween and The Exorcist have both done, to name a couple – but would never have such a profound effect on the studio system four decades after its release. It does admittedly have its share of darkened set pieces and even jump scares, and it spends a good chunk of its time building up its near-unstoppable villain the way another film might build up the mythology of a vampire or werewolf. Jaws hasn’t endured for so long after its initial success merely on the strength of its scares and its monster but, I’d argue, thanks to its characters and deft juggling of tone. A horror film’s final minutes are filled with dread and hopelessness, while those of Jaws are instead strangely hopeful. Aboard the rusty little boat, the three men come together despite disparate personalities to work toward a common goal as John Williams’ triumphant score swells in the background. There’s no hopelessness here, but an unexpected sense of awe and adventure that belies the fact that one of those three men will soon be messily devoured by a great white—we’ll get to that later though.

It Starts With the Script

John Williams can’t take all the credit, when in fact Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb’s screenplay deserves most of it. The script finds economic ways to build up the setting of Amity Island as well as the journeys of the three main characters, who only truly take center stage in the film’s thrilling second half. Brody (Roy Scheider), Quint (Robert Shaw) and Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) are all brilliantly written and cast. They fit into neat archetypes—family man, burly blue-collar fisherman, pretentious young scientist—without ever feeling like stereotypes, thanks in part to the skilled actors who play each part. All three are eventually driven by their common goal, but the script and direction distinguishes them and makes each motivated to kill the shark for their own reasons—Quint’s bone-chilling monologue being the most famous of the lot. There is time for other characters in the film’s two hour runtime, but the focus is placed squarely on them and the shark, building up the threat and their connections to it, so that once the film reaches its climax, there’s no need for the action to come to a halt so Brody can announce, “Hey, I’ve faced my fear of water now.” Many movies would make that exact mistake.

The Avengers, Adrift at Sea

Here, in the clashing and eventual bonding of strong personalities, in the wise-cracking while staring down impending doom, is the blueprint for modern blockbusters such as The Avengers. The Avengers doesn’t have the visual panache of Jaws—few films do, but we’ll get to that too—but it succeeds thanks to its hero’s personalities, courtesy of director Joss Whedon, whose TV shows have always soared on their characters instead of their high concepts. Like so many other blockbusters, all Marvel films can be similarly traced back to Jaws, where Spielberg perfected a guide for future generations on how a film can be both fun and horrifying at once. To their detriment, Marvel tends to complicate their plotlines with extraneous characters and set-pieces, and they’ve yet to craft a villain as memorably terrifying as that damn shark.

Jurassic World’s Jarring Waters

More recently, Jurassic World—of all films that should have learned from Spielberg!—failed for neglecting to apply any worthwhile lessons from Jaws. There's little time for that indescribable Spielbergian sense of awe in the film, even if it does once lazily employ John Williams' original Jurassic Park theme. Indeed, there's little time for anything really in such an overstuffed blockbuster. So many characters share the screen time with little to no effect. Director Colin Trevorrow and the other writers created a film centered on roughly a dozen badly telegraphed stereotypes when crafting three characters anywhere near as interesting as Hooper, Quint and Brody would have sufficed.

Much has been made of the most gruesome death in Jurassic World as a moment where the film went too far, but what of (spoilers for a 40-year-old film) Quint’s death? Spielberg certainly doesn’t spare us the grisly details, as there is indeed far more blood in his encounter with the shark than in Zara’s with the pteranodons. The difference is that Quint’s death serves a narrative purpose and makes sense for the character—we understand his long-held vendetta with sharks, and we know he has something of a death wish, so it’s all but inevitable. Meanwhile, Zara’s death is a lengthy one for a minor character, not so much intended to tug heartstrings or fulfill any journey but to make full use of the CGI pteranodons. Without reason, the death just feels mean.

The death scene in Jaws, perhaps most importantly of all, is part of a series of escalations. Jaws is maybe the purest example for the virtues of escalation in film. Aware of the visual shortcomings of his animatronic shark, Spielberg was careful to keep shots of the monster few and far between, starting from the simple image of a fin flapping above water and ending with the titular jaws chewing through Quint’s torso. There’s a logic to the film’s progression that creates mounting tension, as Brody, our chief protagonist, is drawn finally into a direct face-off with the shark. Compare that to Jurassic World, wherein the Indominus Rex is shown early and frequently but without any sense of scale, and the characters mostly exist to be put in harm’s way and eventually unleash the t-rex from the first film.

Cinematography of the Sea

Upon rewatch, one facet of Jaws stands out as a relic, something that unfortunately hasn't endured into modern blockbusters – its cinematography. Spielberg uses energetic editing techniques as well as he uses long takes, deftly staging conversations about closing down the beach so they become as visually interesting as each set-piece. There’s plenty of dialogue in the film, but there’s just as much blocking, blocking that creates interesting power dynamics within shots and speaks to how the characters interact with each other and the community around them. In terms of editing, just look at the second shark attack scene on the beach, where Brody watches the beach for any sign of trouble and Spielberg’s camera takes inventory of each moving part in the scene to create tension and put us into the character’s mindset. Such nimble editing and visually striking shots remain a rarity today.

The First Blockbuster

As media ages, it can begin to lose its luster. To its credit, Jaws has lost just about none of its original impact, though killer sharks might not seem so novel now as they were in the mid-70s. The storytelling, the cinematography, and the plain but effective character work remains as brilliantly realized today as it did forty years ago. In fact, in some respects it seems even more impressive, as so many blockbusters since have tried to approximate its magical mixture of horror, humor and adventure without nearly as much success. Many future films will continue to learn from the primo storytelling of Jaws, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the first modern blockbuster remains the best.

Review: 'Me and Earl and the Dying Girl'

It’s hard to deny the power of the two anchoring performances in Me and Earl and the Dying Girl—those of Thomas Mann, or Me, and Olivia Cooke, or the Dying Girl. Mann plays Greg, a reserved teenager whose high school life depends on a carefully cultivated neutrality and lack of involvement, soon threatened when his mother decides he should befriend an ailing classmate he barely knows. So we meet Rachel (Cooke), a teenager recently diagnosed with cancer who rejects Greg’s obligatory pity before she’s eventually charmed by his awkward magnetism.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl thrives on the strength of these two characters and the easy chemistry of the perfectly cast young actors. Their first full scene together, wherein Greg breaks through Rachel’s depressed façade with some off-the-cuff observations about the attractive pillows in her room—don’t worry, it works better in context—is easily one of the film’s best.

Though this relationship is surely the film’s most important, it doesn’t always get the focus it deserves, as the film spends much of its time rounding out the supporting players in Greg’s life. Greg makes art-house parody films with his best friend, or “coworker” as he insists on calling him, Earl (RJ Cyler), he endures the doting of Rachel’s wino mother (Molly Shannon), he enjoys exotic foods courtesy of his anthropologist father (Nick Offerman), he watches movies during lunch in the office of a cool teacher (John Bernthal)—the list goes on.

There’s real poignancy to the tale, as Greg is forced to confront his own feelings of self-hatred along with a newfound fear of death that comes from being in such close proximity to someone who is really, truly, slowly dying.

There are certain clichés that almost inevitably come with any modern independent coming-of-age tale, and unfortunately, despite its strong lead performances, Me and Earl doesn’t completely avoid those clichés. The movie hinges upon the arc of Greg, a mostly well-sketched character whose crippling self-esteem issues come to the film’s forefront once he unwillingly embarks on a near-endless endeavor to create a movie for Rachel. There’s real poignancy to the tale, as Greg is forced to confront his own feelings of self-hatred along with a newfound fear of death that comes from being in such close proximity to someone who is really, truly, slowly dying.

It’s puzzling then, why director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon felt the need to dilute the poignant tale with so many extraneous stylistic choices, with so much quirk. The movie opens with an unrelated voiceover and a couple cutesy claymation interludes as Greg ponders the best way to begin a story—both the claymation interludes and the voiceover continue intermittently and unnecessarily throughout the film. In one scene, Earl and Greg get unexpectedly high, and even hallucinate giant costumed animals, after consuming some mysterious drugged comestibles. One puzzling subplot involves a pretty classmate who unknowingly leads Greg on, only for her to inevitably profess actual interest in him, though he’s hardly said more than a dozen words in her presence.

It’s not that these clichés are inherently bad, but it’s hard to justify their existence within the context of Me and Earl, when the film’s runtime would be better spent allowing the characters to develop naturally. While Greg may be well-drawn, many of the supporting players never get their fair share of screen time or development due to the film’s preoccupation with such quirk. In spite of his title billing, Earl for one never really develops beyond a straight-shooting comic relief who occasionally doles out information on the source of Greg’s insecurities, hinting at strained relationships with his parents—relationships that also get short shrift. The film is instead crowded with diversions that don’t really do anything to propel the narrative or its characters forward. Plus, they’re just not very funny or interesting.

It’s a shame, as Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is often far smarter than its cookie-cutter coming-of-age plot might imply. There’s a lot to enjoy when the film occasionally finds its groove, letting the characters develop and bounce off of each other naturally, but there’s a lot to groan about too. The former slightly outweighs the latter, and the film is made worth seeing thanks to the occasional flashes of brilliant writing and the strong cast.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl opens at the ArcLight (and other major theaters) this Friday, June 12th.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2qfmAllbYC8

Review: 'When Marnie Was There'

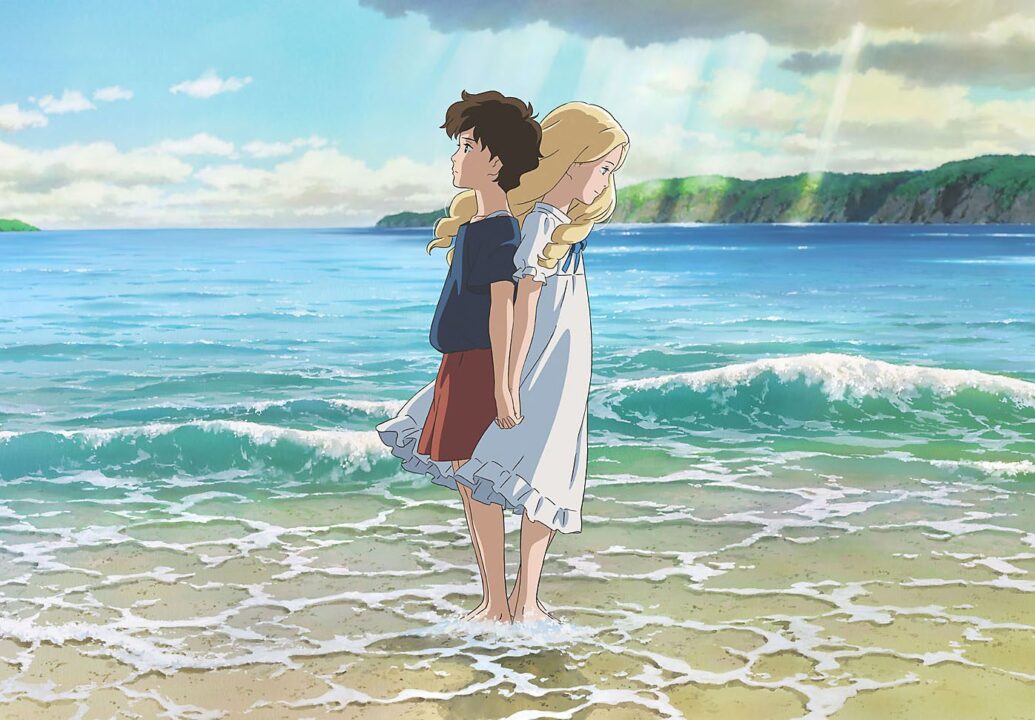

With little exception, the characters around Anna, the young protagonist of When Marnie Was There—Studio Ghibli’s latest and last film, at least for a little while—find her off-putting, and she is off-putting. Her own insecurities, most of them related to her background in the foster system, often manifest themselves through panic attacks and puzzling disdain for those who try to befriend her.

While Anna may be alienating, particularly compared to the long line of other, warmer Studio Ghibli female lead characters, the world she occupies is anything but. Ghibli’s films have always been lush and lovingly drawn, but When Marnie Was There seems especially beautiful. Each surface and every detail has an indescribable texture like a more vibrant, inviting version of real life. It’s easy to detect every ripple of water, or to feel every impact of a gust of wind on the characters.

Hirosama Yonebashi’s second feature as director after the more lighthearted The Secret World of Arrietty is also one of the studio’s first since the retirement of founding pioneer Hayao Miyazaki. If anyone doubted Yonebashi’s talent as an animator (but why would they?), When Marnie Was There provides further proof, as the world he creates is stunningly rendered, though the creativity of the characters and the creatures within it don’t match the level of sheer invention established by Miyazaki’s best work. To be fair, it shouldn’t have to be. While Miyazaki’s work was far more fantastic, Marnie has its roots in Victorian-style classic literature, as it is based on a novel written by British author Joan G. Robinson in the 1960s.

Each surface and every detail has an indescribable texture like a more vibrant, inviting version of real life. It’s easy to detect every ripple of water, or to feel every impact of a gust of wind on the characters.

While the film’s landscapes may be open and inviting, the story is less so initially, but as the details begin to unfold and the characters develop it does open up. Anna is sent by her guilt-ridden foster mother to stay with relatives in the countryside to help both of them get well after some recent psychological troubles.

Though Anna’s new guardians are friendly as can be, she still feels like a hopeless outsider, and compulsively does her best to remain one. That is, until she meets a radiant young girl named Marnie, who lives in a mysterious mansion across the lake, with whom she has an instant connection with. Of course, their friendship is made difficult by the strange supernatural goings-on that slowly seem to drive them apart.

Although the plot never once becomes truly surprising, the familiar story is deepened by the richness of emotion that slowly develops over the course of the movie. Yonebayashi cultivates a very distinct, eventually engrossing, atmosphere with almost every facet of Marnie that when the emotional revelations pay off in the third act, I found myself particularly invested in the characters and their emotional states. Anna may be difficult, but her relationship with Marnie allows her the depth any good protagonist deserves.

This isn’t a perfect film by any means. The film suffers from story flaws in its occasionally slow pacing and muddled, disorienting chain of events a little past the midpoint, though such flaws are easily overlooked for the most part.

I can easily imagine how some viewers might be unaffected by the inexplicable emotional connection I felt while watching When Marnie Was There, but it’s hard to deny the film’s aesthetic beauty and emotional delicacy. At its best, When Marnie Was There feels like a half-forgotten memory of an idyllic childhood dream—nostalgic, beautiful and tragic in the deeply felt passage of time and its suggestion that ideas like love and family can somehow transcend it.

When Marnie Was There is now playing at Laemmle Theatres.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-sixU3ZrXg

The Unique Appeals of the Private Eye Protagonist

Doc Sportello, the private eye protagonist of Inherent Vice as played by Joaquin Phoenix, doesn’t look to be the picture of sanity—a frizzy haired, barefoot hippie so often clouded by flumes of marijuana smoke—but he is in the surreal slice of the 70s he occupies. Director Paul Thomas Anderson's adaptation is an obvious homage to film noir, and Doc being the film’s fractured, updated take on the hard-boiled detective. Though film noir is often treated as a relic, the genre is thankfully kept alive by neo-noirs like Inherent Vice, and the detective heroes remain as relevant and uniquely appealing as ever.

The noir detective, as most of us understand him, began in Raymond Chandler’s stylish Phillip Marlowe novels, and thrived in film as a different kind of American hero. He is a sort of counterpoint to other mythologized American heroes, like the white hats in Westerns. Noir follows the hard-won victories and more often, the hard-lost failures of Humphrey Bogart, rather than the unwavering horseback heroism of John Wayne. Detective tales suggest that American life molds good men not into idealistic heroes but into cold-hearted cynics.

The audience still identifies with the private eye, however, because he isn’t all cynicism. The noir characters of Humphrey Bogart and other actors of his ilk retain shades of idealism. For all their swagger and smart-mouth, the film noir hero could easily be a version of a Jimmy Stewart everyman who surrendered his small-town notions of a righteous world after years spent in a big city lousy with injustice. Bogart has a romantic side in him, as seen in the film adaptation of Chandler’s The Big Sleep, wherein he takes decisive steps to protect Lauren Bacall’s Vivian Rutledge. Though their courtship is anything but traditional, Vivian challenges Phillip’s cynicism and detachment.

••

If a good story is about how the chain of events affect its main character, detective pictures are often about cynical men tricked into exposing a well-hidden core of idealism, until a harsh turn of events forces them to return to cynicism.

Films have to challenge their protagonists and dare them to change, so most detective noirs focus on the cases that coax the steely hero out of his protective shell of cynicism. In most films, our protagonist takes decisive action to change his life, but the noir hero, as a cynic, has to be willed into action by money and is only gradually drawn into his own story by an increasingly surreal case. They are motivated first by money, and then by mystery, and finally by that bit of Stewart-esque idealism the case arouses inside of them—most often by a dame who isn’t all she seems to be.

The most important distinction between noir and other Hollywood fare, both in the 40s and in the present, is in the ending. Most films detail the struggles and eventual triumphs of those who finally take action. The typical Hollywood flick ends happily for the protagonist, thanks to the actions they take. Usually, if a Hollywood character suffers a sad ending, they’ve done something to deserve it, as is the case for Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) in Double Indemnity, one of the most famous noir films not focused on a private eye. Film noirs reject the idea of happy endings, even for admirable characters. This is a genre wherein the characters are almost inevitably doomed to some sort of misery from the opening credits on. If a good story is about how the chain of events affects its main character, detective pictures are often about cynical men tricked into exposing a well-hidden core of idealism, until a harsh turn of events forces them to return to cynicism.

Take Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) in Chinatown, one of the greatest noirs of them all. Gittes follows the mystery and its leads competently for most of the film, but only in the third act does he truly intervene, to save the unusually vulnerable femme fatale, played by Faye Dunaway. He isn’t rewarded for his noble intentions, however, but punished for them, as his implied personal history repeats itself and his intervention leads to further tragedy.

••

Detective stories preach something more cynical and often all too true—no matter how pure our intentions, they can still accomplish nothing, as in Inherent Vice, or worse, result in nothing but misery and tragedy, as in Chinatown.

In Inherent Vice, Doc stumbles upon some kind of conspiracy, but he, like the audience, can never quite put the pieces together, let alone change the course of events or hurt the international syndicate that will soon consume his hippie lifestyle, just like it apparently consumes his old flame Shasta’s identity. While Chinatown suggests Gittes can only make things worse by trying to help, Vice presents Doc as a do-gooder too weak to really affect change or reverse injustice. The Big Lebowski, another pot-heavy neo-noir, lets its lead determine his own destiny. Though he certainly loses something in his struggles to reclaim a soiled rug, The Dude’s (Jeff Bridges) distinct brand of laid-back cynicism means he gets his own sort of happy ending after all, simply by being allowed to continue his life.

Each of these endings flies in the face of traditional Hollywood endings. Most movies preach that taking matters into your own hands will end with love and success, or at the very least some kind of happiness. Detective stories preach something more cynical and often all too true—no matter how pure our intentions, they can still accomplish nothing, as in Inherent Vice, or worse, result in nothing but misery and tragedy, as in Chinatown. The Dude is a rare exception to the rule, but even then, his happiness doesn’t come from action and from change, but simply from being satisfied with where he’s at. The Big Sleep is admittedly another exception to the rule, but I’d argue the movie is weaker for softening the novel’s darker ending.

Private eye protagonists are far from the norm, and that’s certainly not a bad thing since the formula would quickly become tired were that the case. Nevertheless, there are reasons film-goers feel compelled to return, and this tragic brand of American hero will continue to survive in neo-noirs through the times, as long as there’s still something to be cynical about, and something to hope for in spite of it all.

Review: 'Backcountry'

Backcountry is titled for its location, but it could just as easily be called Worst Case Scenario for the events that play out. The real-life horror’s strengths lie in its plausibility—we’ve all imagined a camping trip gone wrong, but seldom of us have really considered the torturous desperation involved.

Neither have the film’s two leads, young lovers Alex (Jeff Roop) and Jenn (Missy Peregrym). Showboating woodsman Alex is determined to wow Jenn by guiding her to one of his favorite spots in the wilderness—one he insists he’s so familiar with that he won’t even need a map. You might guess where this is going.

Despite the Based on a True Story title card that appears as the couple paddle their rental canoe into the woods, the first half of the film follows familiar horror beats, often teasing viewers into guessing what might go wrong: Will they be attacked by hoodlums as the park ranger warns they might? Will Alex’s nasty blow to the foot come back to haunt them? How fresh are those bear tracks on the trail? What’s the deal with the creepy Irishman (as played by a smirking Eric Balfour) they mistakenly share their dinner with?

Despite all this potential, the film is remarkably restrained for most of its running time. Only small things go wrong mostly, but given their isolated surroundings, the minor misfortunes easily pile up to create a palpable sense of fear and desperation threatening to end in grisly death.

The grueling and often alienating experience is likely an attempt to mirror what being lost in the woods is actually like, but so much of the same makes it easy to disengage from a film as self-serious as Backcountry.

The camera is mostly handheld and often purposely disorienting. In one climactic scene, the soundtrack and shaky-cam thrillingly convey the chaotic nature of the events—we experience the horror as the characters might experience it. Elsewhere the gimmicky cinematography and synth-laden score often undermine the tension and sometimes-immersive atmosphere, working against the film more than they work for it.

Despite some easy couple’s banter in the first half, the plodding desperation grows tiring for 90 minutes of wandering through the woods. The grueling and often alienating experience is likely an attempt to mirror what being lost in the woods is actually like, but so much of the same makes it easy to disengage from a film as self-serious as Backcountry.

Admittedly, all that self-seriousness has a worthy pay-off. The tension created by an hour-plus of strong acting and minor terrors eventually culminates in one of the most gruesome scenes I’ve seen in a recent film. The climax is in fact so effectively horrifying that the action that follows seems almost unnecessary.

I did not enjoy watching Backcountry, which isn’t to say I don’t like it. Director Adam MacDonald has a strong grasp on what makes nature so beautiful and what makes it so terrifying, even if he sometimes loses sight of his film’s pacing in favor of brooding realism.

If you like your horror with plenty of honest-to-God jumps, see this film. Conversely, if you're planning a camping trip sometime soon, avoid this film at all costs.

Backcountry opens in Los Angeles this Friday.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46uwmzTf5nA