Share a Drink and Some Stories With Charles Himself, in 'You Never Had It: An Evening With Bukowski'

Quick Take: You Never Had It: An Evening With Bukowski is at once both a wonderful portrait of the wise old drunk at the end of the bar and a sorrowful depiction of an artist relegated to continuously maintain the character that brought the success that pulled him from the world that breathed the life into his stories.

Oft times things are expected of people who create a world we long to inhabit. A world we’ve spent hours, days, even years imagining creates expectations that tinge the real human who dreamed them up to begin with. I worry this piece (and my view of this film) is entirely altered by my having spent a portion of my life imagining myself through the arms, feet, eyes, and ears of his characters. That’s the point though. That a truly transcendent artist creates a definable but vague enough canvas for us to paint ourselves into their lives and creations.

Likewise, standing on a stage you’ve dressed long enough can blur the lines of performance. The many fictional depictions of “Hank” certainly altered the light of Charles himself.

When you interact with a subject like Bukowski you must first understand that whatever it was you’d intended for your piece to be it won’t be without first being taken in and filtered by the subject into what he perceives it as.

This evening (edited to fifty-plus minutes) of revelry in a San Pedro apartment is no different. No question, no comment, is left untinged by his light.

At once both a wonderful portrait of the wise old drunk at the end of the bar and a sorrowful depiction of an artist relegated to continuously maintain the character that brought the success that pulled him from the world that breathed the life into his stories. This film is littered with one-line genius, advice, and witticism as a forest floor is with leaves in fall. A veritable graduation speech for anyone who ever dreamed of holding a pen and breathing life into paper.

The interviewer keeps begging to draw him into the more base and dime-store aspects of his writing. Something he waves a smoky hand at.

“Why is everything sex? Can’t I ride a bicycle down the street without thinking about sex? Am I an impure person because I don’t think about fucking? Is my mind wrong because I don’t have a hard-on fifty-percent of the time? I’ve got nothing against fucking, but it can be overpriced.”

“But that’s what you write!?” She retorts.

“I have fucked and I have fucked well and I’ve written well about it, but that doesn’t mean it's very important.”

This is perhaps the truest moment of the film. Where the artist is confronted with the perception of his creation and rejects it outright.

The interviewer is asking him to roil in the muck that churned the loins of his fans and he verbally rolls his eyes and moves on.

Anyone who creates knows that when you, lantern in hand, forge the path of creation through the dark and go back and share your map, that anyone who trails after you will only experience that path through the tinged light of their experience. They are not going to feel, or learn what you did. Their path down yours is theirs, and Silvia’s was more interested in his sexual exploits than the beatings his father gave him.

Just as mine was more interested in the topography of his surroundings and the flavor of the bars he frequented than his pain of being misunderstood again and again.

He in fact addresses his female fans by saying he much more appreciates if they actually read the books, and describes sex with his girlfriend as “getting it out of the way” so he can get to the Tonight Show. Both sentiments could be taken under the popular lens of his being a misogynist, but I think this minimizes what he said earlier.

“Why is everything sex?”

He answers that with, “Because It Sells.”

“Is that the only reason?” Silvia asks.

“Of course.”

He is stating plainly and clearly that the more debauched parts of his writing weren’t to debase his work, but to appease his base.

It is just “not very important”, or at least not as important as riding a bike.

Maybe a hook to pull in and elaborate on pain. Real and true pain. To draw in with the glitter of love and the debauch the whole affair with a seven-chapter diatribe about child abuse.

He later regales Silvia with a story about an attractive woman he encountered at a party, while his girlfriend looks down and away clearly disappointed. Maybe thinking back to only a few minutes prior when his description of their sensuality could have easily been used to describe a bowel movement, and imagining to herself that when he said that sex wasn’t that important, he meant theirs too.

He did. He said so.

“Writers are very despicable people. Plumbers are better. Used car salesmen are better. They’re all more human than writers. Writers save their humanity till they sit down to a typewriter, then they become good people or exceptional people. Get them away from a typewriter, they’re pricks. I’m a writer.”

So sitting there without a typewriter he is telling you exactly what to expect of him. He is telling you precisely who you should expect him to be. That any humanity he had had been typed into his work long ago and if you needed it it was there. He sees the world that way, but it is through his story of the Hemingway picture that you can see how he sees himself at this point in his life. When he shows the picture of a literary icon none of us should see. An intimate portrait of how success taints genius. It might as well be Kerouac or London. It wouldn’t mean anything different either way.

Because, “Talking to another writer is like drinking water in a bathtub.” Sure, the glass is fresher, but isn’t the soil washed from the surface what you wanted from them all along?

To be able to get drunk with Chuck through the lens of a camera is quite a spin. The kind that blindfolds you, and leaves you dizzy, bat in hand in front of a paper mâché version of who you thought you were and begs you to try and find the person so covered with who we wanted him to be. So don’t.

“Don’t try.” Watch.

"Somebody asked me: "What do you do? How do you write, create?" You don't, I told them. You don't try. That's very important: not to try, either for Cadillacs, creation or immortality. You wait, and if nothing happens, you wait some more. It's like a bug high on the wall. You wait for it to come to you. When it gets close enough you reach out, slap out and kill it. Or if you like its looks, you make a pet out of it."

'Mr. Roosevelt' Review: Dealing With The Loss of The Cat (See Also: Man) Left Behind

I should apologize up front for the bared emotion bound to litter this review, but I won’t.

For anyone who ever followed an unfiltered thought into a mid-day dance down a busy street and stopped only to wonder, Why are these people laughing?

Thank you, Noël. I slept much better last night. Something I wasn’t sure I’d say again before you showed me what burying the ashes of a cat could do. Don’t dwell on the past. Or do, and see this film if you need a nudge because, I mean, “Are you willing to be reborn” or not?

'Mr. Roosevelt' is not rated. 90 minutes. Opening tomorrow at Arena Cinelounge Sunset.

'Maya Dardel' Review: Young Male Writers Compete for Unusual End-of-Life Offer

From the opening shot, the very first hammer to chord, the burden of the legacy of an artist lays over the drama Maya Dardel.

Be it flailing toward greatness or at their own hand, if the protagonist, supporting cast, writer, director, and even its crew will be remembered for the work they’ve done before departing our world, they will be remembered fondly and with respect.

Maya Dardel, played masterfully by Lena Olin, is an aging heirless writer who, believing her talent to be fading, proposes a game-like process for young male writers to essentially come and woo their way into her estate. Judging their work, their knowledge, and in part their skills at cunnilingus, Dardel whittles down the entrants to two– the deft, coy, and curious Ansel (Nathan Keyes) and the crass, obtuse, and admittedly untalented Paul (Alexander Koch). They play off each other as opposites and in fact may as well be the angel and devil on Maya’s shoulders. She essentially casts and directs her internal struggle to play out in front of her. The love and loss. The triumph and the struggle. Or as she says it herself, “We can live in a state of denial, or an unhealthy state of mortality.”

In fact, the entirety of the cast could all be varied parts of the same woman, struggling against each other, leaving us to believe she hands over the keys of the estate to the part of her she wishes to continue on in her name. Though, in her words again, “Death beautifies even the ugliest vanity.”

From the opening shot, the very first hammer to chord, the burden of the legacy of an artist lays over this film.

The intrinsic loneliness of being a person whose imagination can create any and every situation one could only dream of being in is on broad display throughout Maya Dardel. This is expressed both visually, through gentle pacing and stunning establishing shots of Dardel's property and emotionally, through the softly read works of Maya and the beautiful piano pieces by the writer, director, and composer Zachary Cotler.

Maya betrays that blatant loneliness through an abuse of power over these young artists, the young men who begin this power struggle through the obsession of her work and a need for what she can give them, be it inspiration, money or land. However, only one ends up realizing his power is greater because Dardel will only be remembered posthumously through the care of the man she chooses. The man appears visually and emotionally larger on screen until the moment he weakens himself to her to the point of shame. This culminates in a very powerful scene, after which Maya and Ansel are walking together, and for the first time her vociferous monologuing shows as a panicked weakness toward, “One of the few men who liked her but managed not to fall into her entourage of slaves.”

At the end, though, aren’t we all just wondering if the work we did left a mark?

This did.

Maya Dardel is unrated. 104 minutes. Opening this Friday at the Laemmle Monica Film Center.

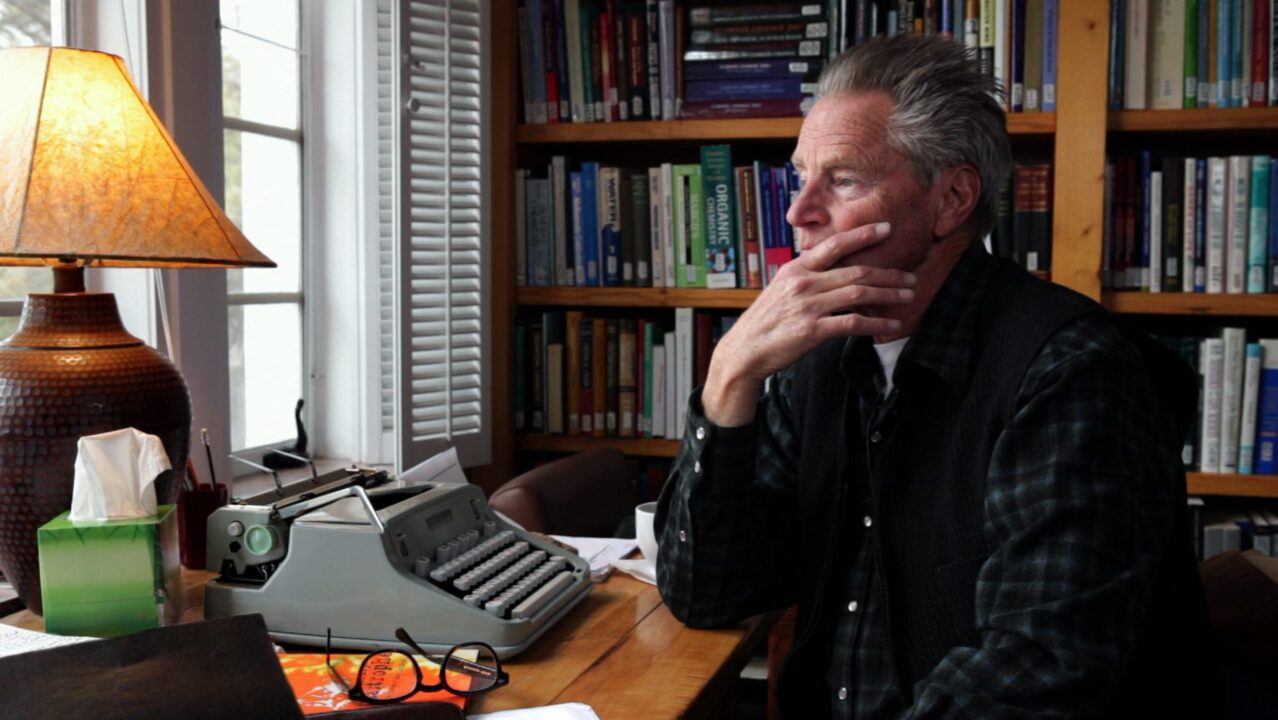

'California Typewriter' Review: A Beautiful Ode to the Tools We No Longer Need

I’ll be wholly honest with you; I’ve never understood nostalgia.

I’m more apt to be found with a copy of “The Life Changing Magic Of Tidying Up” than a history book, but here I am hammering away on a Selectric I thrifted from my local Goodwill after seeing this film and I can’t help but think I’m better for having changed my mind on the importance of the tools we use to create.

Part love letter and part eulogy, California Typewriter is, at its base, a trip down memory lane in search of the right keys to press to quell that panging thirst for expression. A series of vignettes that begin as peeks through the blinds at mad men shouting in the street about the dangers of technology end up more like tear jerking love letters to the tools we use to speak to one another and the value of history to art. Somewhere along the line, probably as the search for the first typewriter ever made brings the film to my hometown of Milwaukee, I found a link to the nostalgia I’ve long been wary to accept, and then the carriage returned.

“The past is a luxurious pursuit,” Martin Howard says of his pursuit of the past: his extensive collection of typewriters. The luxury to consider the meaning of our tools over their efficacy is precisely the type of pursuit that is possible in part because of the efficacy of the tools that replace these older, more beautiful ones, which is the point. That the freedom to choose allows us to decide what makes us smile over what simply gets the job done. The pursuit of the history of the typewriter is the pursuit of the history of more readily available language, love, thought, and news. It is more interesting than it’s listless paragraph in the Wikipedia entry for the 'typewriter.' Until, that is, you look down that path and notice each twist and turn caused by each foot to have tread this path before you. A well-worn path isn’t valuable in itself, but as a way to the place it leads you. The vista that director Doug Nichol leads us to is a beautiful view into how the machines that transcribed generations of thought affect us today.

"California Typewriter" is a beautiful ode to the tools we no longer need to use but should find a reason to keep around for the value they hold above their use.

The tools we use to create carry as much the burden of the creation as we do. In part, the technological changes of this century have allowed even more of those important thoughts and letters to fit so neatly somewhere in the digital clouds over a struggling typewriter repair shop outside San Francisco. However, what we’ve lost may be more important than what we’ve gained by the convenience of progress. The physical connection to the art we create with words is what we’re asked to believe has disappeared with the abundance of all these digital options. An argument I came around to with equivocating the typewriter to its counterparts in the musical world was literally in the case of the Boston Typewriter Orchestra. A group that uses the clinks, clanks, and dings of old typewriters as their actual instruments.

California Typewriter is a beautiful ode to the tools we no longer need to use but should find a reason to keep around for the value they hold above their use. See this film because you like obscure history. See it because you just want Sam Shepard to break your heart with his words one more time. See it for whatever reason you need to, but see it. It’s easy to dismiss something because it’s old and seems irrelevant, but to notice it’s there is all the more amazing because of that. It’s something to be revered, something to be cherished, and something to be remembered. Like your grandparents. Who by the way, would like you to give them a call.

*/ I should note that I have John Mayer’s words to thank for my change of heart. I’ll add it to the list of romantic evenings I owe him for and send him a nice typewritten ‘Thank You’ letter. That’d make Tom Hanks proud too, I suppose.

"California Typewriter" is unrated. 103 minutes. Now playing in select theaters in New York, opening August 25th in Los Angeles.